A lingering wound in Chilean history, the coup d'état that overthrew the democratically-elected government of Salvador Allende and imposed a 17-year dictatorship also deeply impacted the country's media landscape. Bombed, arrested, censored, tortured, exiled, and sometimes killed, Chilean journalists nonetheless fought to report truths that were inconvenient to those who seized power.

Marking the 50th anniversary of the coup this Monday, recollections from Chilean journalists about that fateful Sept. 11, 1973 serve as a testament to their tenacity, courage, and bewilderment in the face of rising authoritarianism. Amid rockets launched against newsrooms and tanks in the streets, media professionals labored to keep radio stations on air, to report from nearby La Moneda presidential palace, and preserve recordings containing historic accounts.

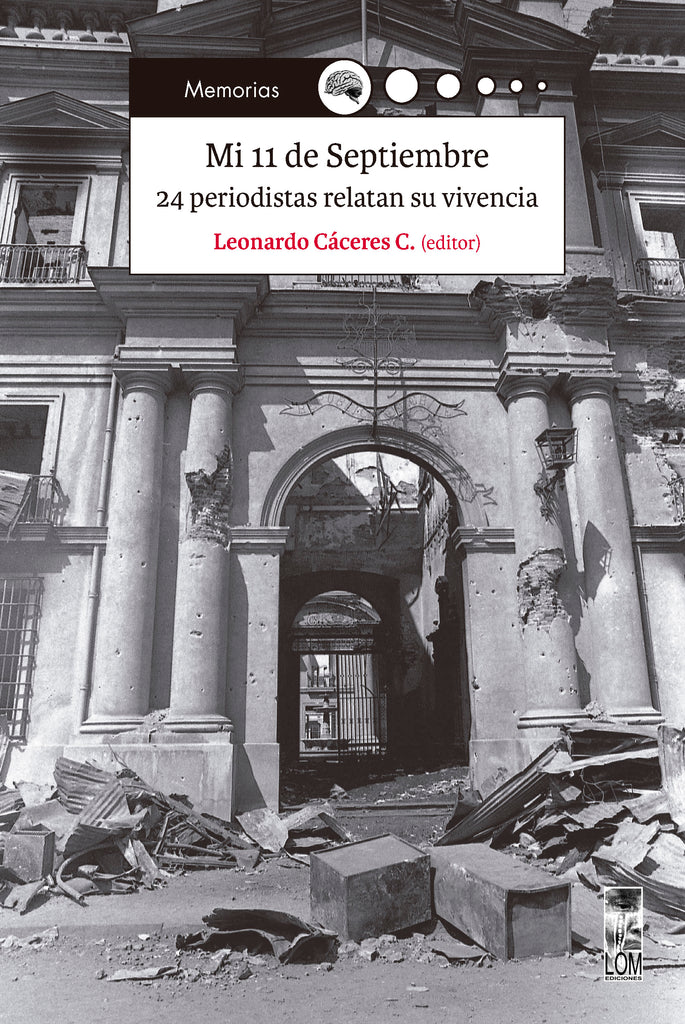

Some of these stories are included in the book "Mi 11 de Septiembre: 24 periodistas relatan su vivencia [My Sept. 11: 24 journalists tell their stories"], published by Lom Ediciones in 2017 and reissued for the 50th anniversary of the coup. The book features 24 accounts by left-leaning Chilean journalists recalling one of the most defining days in the nation's history. According to its editor, Leonardo Cáceres C., the work is "another effort to combat the collective amnesia that sometimes afflicts Chilean society."

Many accounts focus on the early hours of Sept. 11, from dawn until late morning when La Moneda palace – where Allende was staying – was bombed by fighter jets. Chile's crisis had been simmering for months, and the anticipation of a coup was palpable. Even before 8 a.m., upon hearing news of a Navy uprising in the coastal city of Valparaíso, journalists sensed they were living through an historic moment.d.

"We knew we were in for an intense day, perhaps one of the toughest of our lives, and that we would have to fully dedicate ourselves to these broadcasts," writes Sergio Campos, a three-year veteran at Radio Corporación who later became the winner of Chile's National Journalism Award (2011) and dean of the School of Communication at Central University.

One of the most crucial accounts in the book details how Radio Magallanes, then part of 'Voz de la Patria,' an alliance of left-leaning radio stations voluntarily supporting the Popular Unity government, fought to broadcast Allende's final speech. The president addressed the nation five times during the coup, at 7:55, 8:15, 8:45, 9:03, and 9:10 a.m

For the last two speeches, Radio Magallanes was the only channel used. Cáceres, then the station's press director, recalls what happened, "[Radio director Guillermo] Ravest told us via internal communication that Allende was on the line and we had to announce him immediately. The controller, Amado Felipo, managed to air the first chords of the National Anthem, over which I attempted to introduce the President. But he was already speaking."

Cáceres then transcribes the opening lines of Allende's historic, impromptu speech:

"Surely this will be the last opportunity for me to address you. My words do not have bitterness but disappointment. I am not going to resign! Placed in an historic transition, I will pay for loyalty to the people with my life."

Less than an hour later, at 10 a.m., Radio Magallanes was bombed and hit with machine-guns. Following a raid, four journalists were arrested, and by 10:27 a.m., broadcasting ceased. Several journalists who escaped left the newsroom with magnetic tapes containing copies of the morning's broadcasts, including Allende's historic speech. Cáceres would later go into exile, returning only in the mid-1980s.

According to the book, Radio Candelaria was the last station opposing the coup to go off the air, losing its signal just minutes before La Moneda was bombed at 11:52 a.m. Jorge Andrés Richards, the station's press director, was caught on the way home carrying recordings of the broadcast and an officer listened to the anti-coup recordings..

"My defense was that our messages had always been a call to defend the democratically-elected government, the Constitution and the rule of law. I stood firm that we upheld republican principles and never called for insurrection or armed resistance. After a few hours, I was released," he said.

The book also describes how disinformation plagued the journalists themselves, who were engulfed by rumors. For example, it was said that General Carlos Pratts, replaced by Pinochet as the Army commander just three weeks prior, had not joined the coup in the south of the country and was marching towards the capital. There were also conflicting reports about whether Allende was alive. By day's end, an informal network had formed by phone among journalists to share reliable information and contacts.

"Together, we managed to set up a news center, gathering as much as we could about what was happening. Already on that same September 11, we learned there were bodies in the Mapocho river, there were companies with workers who were barricaded, and that some were later arrested and others shot," said journalist Gladys Díaz, who was also a supporter of the Revolutionary Left Movement (MIR, by its Spanish acronym)."

All the journalists featured in the book consider themselves to be left-leaning and worked for news outlets that supported the government. Almost all of them also had party affiliations. This book leaves out another angle of the events of that day: the point of view of journalists, whether left-leaning or right-leaning, who worked for Chilean news outlets that supported the coup. This viewpoint is only briefly touched upon in one of the accounts, where a journalist, on his way home, crossed paths with two conservative colleagues who were bewildered by everything that was happening.

Book cover of 'Mi 11 de Septiembre: 24 periodistas relatan su vivencia'

With the Chilean press suppressed, many professionals sought refuge in foreign media or left the country, such as Jorge Piña, who later became a Rome correspondent. Those who stayed lived a different kind of exile, according to Enrique Fernández.

"Those of us who didn’t go into exile became internal exiles. News outlets in favor of the constitutional government were shut down. We couldn’t work in the military-controlled press for two reasons: or rejection of the dictatorship and our names being on 'blacklists' compiled by some of our colleagues who were supporters of Pinochet's regime. In response, we organized clandestine information networks to broadcast abroad what was happening," Fernández said.

The new edition of the book was launched on July 25 at an event hosted by the University of Chile. The event featured the participation of the President of the Republic, Gabriel Boric; the Minister of the Interior and Public Security, Carolina Tohá; the Minister of Justice, Luis Cordero; and the Minister of National Assets, Javiera Toro. Various university authorities and media representatives were also in attendance.

On this occasion, editor Cáceres offered reflections on the book's intent.

"In this year, and on these days that mark the 50th anniversary of the civil and military coup, we believe the authors of this book and the journalists who worked on that fateful September 11 are both survivors and privileged individuals. We were both observers and protagonists of a historic event that profoundly affected the country and all Chileans," he said. "Memory serves as both past and present and is essential in shaping our future. That is why we present this book."

(Banner Photo: Julio Pinar Ferrada- CC BY-SA 2.0; Feature photo: Biblioteca del Congreso Nacional de Chile/ CC License 3.0)