How can artificial intelligence and satellite imagery be harnessed to find potential news stories?

That was the question a group of journalists from the Americas asked themselves during their participation in the Collab Challenge 2021 program, a global initiative of JournalismAI and Google News Initiative that brings together media from several countries to develop innovations in journalism through artificial intelligence.

From Above, a guide for journalists on how to use artificial intelligence to identify visual indicators in satellite images and develop journalistic investigations based on it, was born out of this question.

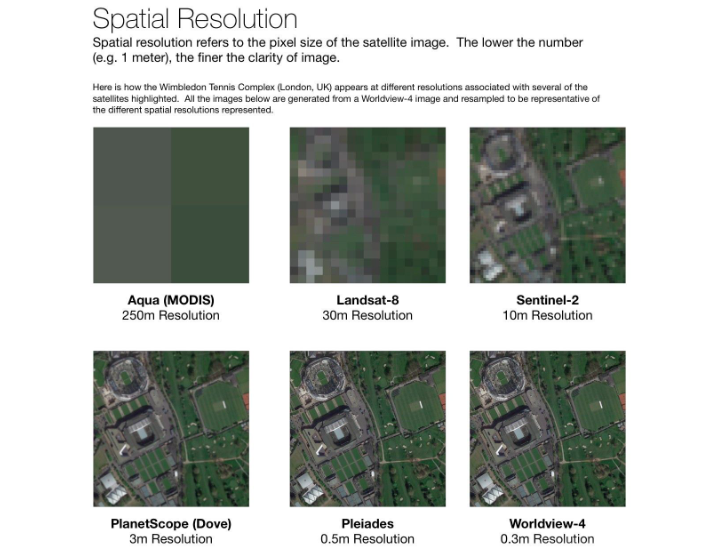

For the analysis of satellite imagery to be effective, images must have a resolution of at least 10 meters per pixel, according to the From Above guide. (Photo: Screenshot from From Above)

While other Collab Challenge teams worked on the development of artificial intelligence tools applied to journalism, the From Above team, formed by Flor Coelho, from La Nación (Argentina); María Teresa Ronderos, from CLIP (Colombia); David Ingold and Shreya Vaidyanathan, from Bloomberg News (United States); and Gibrán Mena, from Data Crítica (Mexico), decided to focus on researching and creating a work guide that could benefit journalists with little experience in the field.

"The product was the complete guide. It was also intended so other journalists without this previous experience could also use these image analysis tools, especially in investigations that have to do with changes in forest coverage and climate crisis," Gibrán Mena, of Data Crítica, told LatAm Journalism Review (LJR).

A Journalist's Guide to using AI + Satellite Imagery for Storytelling consists of eight steps that explore how to use computer vision as an innovative way to gather potential investigative reports.

The first step in the guide (1) is to think of stories in which visual cues could provide additional context or evidence. In theory, almost any phenomenon that leaves visible marks on the earth and can be captured from space is likely to be analyzed with artificial intelligence, according to Mena. This can range from land erosion and deforestation, to the detection of drug dealers’ airstrips or illegal ranches.

For the development of From Above, the team chose to investigate deforestation by extensive cattle ranching in Mexico and Colombia.

The next step in the guide is the acquisition of the data (2) — or in this case, the satellite images of the area of interest — at the appropriate resolution. According to Mena, this is one of the most complicated stages, since for the analysis of the images to be effective, they must have a resolution of at least 10 meters per pixel.

"This is a big challenge we face because [...] the companies that own the satellites are naturally interested in making a business model out of the images. They are extremely expensive and in some cases you need to ask the satellite to take a specific shot of an area," Mena said.

Once the images have been acquired, the next steps in the guide are technical analysis (3) and labeling (4). In these steps, journalists manually examine the images for clues visible to the human eye of what they are looking for and tag them. This work should be done by journalists or investigators who have field reporting experience on the subject of the investigation.

"The key is how do I show a machine what it looks like, what are the pixels in an image that mean to a human eye deforestation caused by cattle ranching, in this case," Mena explained.

These expert journalists mark the images through a labeling process that consists of drawing polygons on what they already know are indications of what they are looking for. Ideally, the images are of places they are familiar with and where they know the phenomenon they are looking for exists.

The signaling is used to associate to the pixels information about what exists there, such as color reflectance, infrared spectrum, shadows and textures, among others. Subsequently, a database is created based on this visual inspection and context data of the analyzed area.

"What this whole process is for is so that when I analyze an area that I don't know with information from other areas, this phenomenon can be detected in an automated way," Mena said.

The next step is the training of the algorithm (5), which is done by combining the information from the satellite image and the signaling performed by humans. This type of training is known as "supervised model training," in which humans provide the criteria that the algorithm must detect in other images.

Then comes the validation stage (6), in which the algorithm is fine-tuned to improve its accuracy. The algorithm's margin of error depends on the accuracy of the labeling.

"It can be above 90 percent accuracy but it can also be well below, depending on how that task was done. There is always going to be a margin of error and there is always going to be a need not to take for granted that the automatic categorization is correct. Rather, there must be a subsequent review process, a human verification," Mena said.

The next step is testing (7), in which the algorithm is run on new images and the results are observed. The final step in the guide is to write the story (8) using the data collected by the algorithm. Either they support the initial hypotheses of the proposed research or they give ideas for new hypotheses or reporting cues.

"The most important part of a technical process like this is neither the tool nor the programming language, but the discussions that went on in the background among the participating journalists," Mena said. "Because without that, the algorithm has no accuracy. The field knowledge of the journalists is extremely valuable for this type of technical process."

For the development of the algorithm that was generated from From Above, the team used R, a free statistical and graphical analysis software that is popular among the scientific community. The algorithm, as well as the database used to train it, are openly available in a repository on GitHub, so that any journalist wishing to do similar research can use them.

"The language used in the guide was thought of for journalists who are interested in knowing what it really means to use an algorithm and who have never had any idea what that means," Mena said. "It's an innovation so that journalists from the global south, from newsrooms that don't have the ability to hire 10 programmers to solve these research problems, also have access to these tools."

Data Crítica is currently implementing the From Above guide in a journalistic investigation on the deforestation produced in the last two decades by soybean cultivation in the Paraná basin, in the bordering territories of Argentina, Brazil and Paraguay. The project is being developed as part of the Consortium to Support Journalism in the Region (CAPIR, by its Spanish acronym), of which Data Crítica is a member along with Animal Político, Armando Info, Fundación Karisma, Institute for War & Peace Reporting and Vinalnd Solutions.

Although it does not yet have a publication date, the story is scheduled for release next July, Mena said.

Shreya Vaidyanathan and Gibrán Mena presented the project during the JournalismAI festival in December 2021. (Photo: Screenshot from the YouTube live stream of the event)

As the authors of From Above experienced, accessing images from space at high resolution is no simple matter. Today, satellite photographs are more available than ever, but images at a high enough resolution to detect objects involve high costs.

The team attempted to contact large companies that own satellites or provide satellite imagery, such as Maxar, Sentinel and Google Earth. However, they found that it is difficult to get a response when the request comes from small projects.

Nevertheless, in their research they found that there are programs and initiatives that allow free or low-cost access to satellite imagery for organizations or journalists seeking to investigate the climate crisis.

“If you look at the guide it might give you a sense of satellite imagery really comes a long way. So you have a lot of free imagery available on the internet thanks to satellite programs that each country has,” team member and Bloomberg News reporter Shreya Vaidyanathan told LJR. “They make images available so that people can study them. They can use them for something. So if you are covering climate [change] or if you're covering a specific geography, as a journalist you can definitely pick those images up.”

The From Above team specifically turned to the Planet platform, an organization that operates 450 orbiting satellites whose mission is to record and distribute images and data of the Earth from space and monitor visible changes. Through Norway's International Climate & Forests Initiative (NICFI) program, in partnership with the Norwegian government, journalists and activists interested in the climate crisis have access to high-resolution images.

They also had the collaboration of Bellingcat, the investigative journalism site specializing in fact-checking and open source intelligence, which has experience in the use of geolocation and satellite imagery in investigations. The site trained the From Above team in the use of Planet's tools and provided them with some high-resolution satellite images.

However, the team acknowledges that, despite the support of these organizations and programs, access to satellite imagery can be a difficult challenge to address. This is in part because investigating changes on the ground requires a series of images over a period of time.

“You want the most up-to-date imagery. If the cost is very large for one snapshot, then it's going to be much more expensive for you to buy it every day or every week or every year. And journalism is, in many ways, short lived,” Vaidyanathan said. “I think it can be useful if you have the skills to manipulate images that are available. And invest in maybe just the skill set to process and analyze them. But the money required to buy fresh, up-to-date imagery is still far from being available for journalism or our newsrooms in general.”

But despite these economic and technical challenges, one of the innovations that From Above brings is the demystification of artificial intelligence and computer vision processes as unattainable elements for journalism, according to its creators.

While the creators of the guide have a background in data journalism and programming, they do not have the technical training of a programmer. And yet, they still managed to develop the guide and train an algorithm. For them, therefore, it was essential that the guide serve as a way to bring other colleagues closer to artificial intelligence in an understandable and accessible way.

"[The media in the developed world] tend to make a disciplinary separation in newsrooms between technical aspects and journalistic research. In our much smaller newsrooms and using other processes different from those used in the north, we can’t make this distinction. The people who do programming are often the journalists themselves, so we did require the guide to be perfectly understandable for a person who does not have tech information," said Mena.

The team initially intended to integrate the algorithm into a graphical end-user interface for ease of use in newsrooms, but the six-month duration of the Collab Challenge was not enough time. However, the team does not rule out creating such an interface in the future.

According to the journalists involved, From Above served as a record of the scope of artificial intelligence to date in the analysis of satellite images to tell stories. As well as to lay the groundwork for themselves or other journalists to apply or improve the process with new knowledge.

“The useful part of our guide is just being like 'hey, this is where this technology is at right now, these are the resources and hope you can sort of make your plans to cover this in a manner that has an impact,’” Vaidyanathan said. “With the scale at which AI and satellite image access is growing, it feels like this can open up a lot of possibilities. If not now, but in just a few years.”