This text was originally published by AzMina on Nov. 23, 2021 and was translated and reposted here with permission.

Attention: The article below shows explicit excerpts of misogynistic and racist content. AzMina chose not to censor them because it feels it is important to exemplify how violent debate looks on networks, how violence against women journalists spreads, what terms are frequently used, and how we can identify it.

“Bitch. She's going to open her legs and give it to Lula.” This was the first message that Eliane Cantanhêde, journalist, columnist for Estadão and commentator for Globonews Em Pauta, from radio station Eldorado (São Paulo) and radio station Jornal (Pernambuco), received on the morning of Nov. 18th. The offensive message arrived in her private mailbox on one of her professional profiles on social media. This, unfortunately, is not the only offensive phrase she receives on her networks. Some are public in the comments section of her posts, documenting the misogyny and violence against women journalists for anyone who wants to see.

Eliane leads a ranking of attacks on press professionals. Women journalists receive more than twice as many insults on their Twitter profiles as their male counterparts. This was one of the worrying findings of a data investigation carried out by Revista AzMina and InternetLab, together with the Volt Data Lab and the INCT.DD, with support from the International Center for Journalists (ICFJ). The growing wave of attacks on the Brazilian press also appears in reports by the National Federation of Journalists (Fenaj, for its acronym in Portuguese) and the Brazilian Association of Investigative Journalism (Abraji). Whether offline or online, violence has the female gender as its main target.

In the survey carried out on Twitter, it was found that users who launch attacks against journalists try to delegitimize women’s intellectual capacity to exercise the profession and silence the press, point out professionals' physical features to divert attention from the topics addressed and disseminate false information about them.

Two hundred profiles of Brazilian journalists on the social network were monitored. Using a dictionary composed of offensive, misogynistic, sexist, racist, lesbian, trans and homophobic words, we collected 7.1 million tweets with offensive content in 133 profiles of women journalists and 67 men. In a more detailed analysis, which considered the period between May 1 and Sept. 27, monitoring reached a group of just over 8,300 tweets, with five or more engagement actions (RT and/or likes). They were checked one by one to identify whether or not the content was a direct attack on the journalist.

Professionals who work with political coverage are more exposed to massive attacks. But, while 8 percent of offensive tweets aimed at male journalists were actually hostile, 17 percent of those targeted at female journalists were attacks. Among the most used terms against them are “ridiculous,” “villain,” “crazy,” “little woman.” Most aggressions also suggest that women are unable to interpret a text or political situation.

For men, the incidence of direct attacks is lower, and offenses are often mixed with attacks on other women or the press in general. Several messages aimed at men also contained misogynistic comments offending other female figures related to them, such as mother, sister and professional colleagues.

According to anthropologist Fernanda K. Martins, one of the coordinators of the research at InternetLab, “misogyny is sustained and spreads socially through movements that target women even when the objective is to reach a man. The attacks directed at female colleagues and family members point to a social behavior that places the female gender as naturally attackable, naturally susceptible to discourses that belittle and disparage women.”

What is seen in common in both are expressions that try to position professionals in political spectrums, calling them "communist" or "journazis," in addition to those who claim that journalists are somehow "partial" in their coverage.

Women journalists are more exposed to attacks on social networks

ORCHESTRATED ACTIONS

At the top of the ranking of the journalists who received the most offenses are Eliane Cantanhêde; Vera Magalhães, presenter of the program Roda Viva, columnist for O Globo newspaper and commentator on CBN radio; Daniela Lima, CNN presenter; and Miriam Leitão, journalist for O Globo, TV Globo, Globonews and CBN. They share the view that attacks are even more virulent when initiated or instigated by political figures, such as President Jair Bolsonaro. AzMina has already shown on its YouTube channel why Bolsonaro's attacks on women journalists are a problem.

A Twitter user responds to Eliane's post about what might happen if Bolsonaro threatens a coup: "There are days when a person is crazy on drugs and decides to write for a newspaper"

Eliane recalls that the attacks on journalists in which they’re named began when the Workers’ Party (PT) had the presidency, by party supporters. She also recalls that she has been heavily attacked by the Brazilian Social Democracy Party (PSDB). The same article displeased both sides. “But Bolsonaro not only used this tactic, he started to discredit journalists by name, which inflamed supporters,” she said.

For Vera, the attacks are strategic. "I understand that they are purposefully misogynistic, sexist, exactly as a way of taking away the credibility of women journalists." She believes that her case is aggravated by the fact that she has made many criticisms of the PT, “and I do against the Bolsonaro government.” But today, the coordination of insults, says Vera, comes from the president, his family and his ministers. “This did not exist in previous governments. It's violent and orchestrated."

Journalist Mariliz Pereira Jorge, columnist for Folha de S.Paulo, screenwriter and presenter for the MyNews channel, says that facing hostility for exercising the profession is unfortunately already part of her routine. The problem, in her opinion, is that the attacks are now more organized and massive. "When a tweet comes from the presidency itself, or from parliamentarians from the governing base, I already know that there will be a flood of insults." And often, in addition to being offensive, the messages are intimidating.

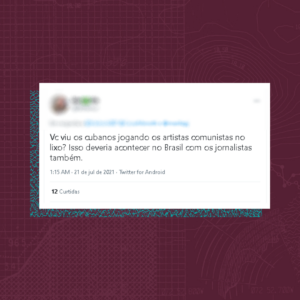

Tweet reads: "Did you see Cubans throwing Communist artists in the trash? This should happen in Brazil with journalists, too."

In addition to swear words, journalists need to fight the dissemination of false news about their careers, which is also a political strategy to discredit these professionals. Miriam Leitão, for example, is constantly insulted with terms such as “bank robber” and “snake woman,” an expression created by followers of President Jair Bolsonaro, who minimized and mocked the episode of torture suffered by the journalist during the military dictatorship.

“I've already been on Twitter's Trending Topics because they used a photo of me saying I was arrested for robbing a bank,” Miriam said, adding that she never carried a gun and this information has already been disproved dozens of times. "But every now and then, it surfaces again." She notes that fake profiles create artificial waves of attack that pollute debate, distort dialogue.

Professionals most attacked

GENDER AND RACE

As is customary in misogynist narratives, women also receive insults directed at their bodies, their relationships and also their ages. With Eliane Cantanhêde and Vera Magalhães, for example, they question their mental health. “They think they offend me, but I never made it a point to hide my age. I'm proud of my history, of the grandmother that I am,” Eliane said.

The professional experience of Vera Magalhães' husband, who is also a journalist and has worked as a consultant to different politicians on the national scene, is frequently discussed on social media as something that supposedly interferes with their career and opinions. A similar strategy happens with journalist Eliane Catanhêde.

The monitoring findings are very similar to those of the report developed by Abraji, which showed a 56 percent rate of online attacks for women journalists in 2020. Swearing, profanity and misogynistic terms were also used when the victims were women. “This scenario draws attention to the need for legal and institutional protection mechanisms for freedom of expression, specifically attentive to the issue of gender,” said Cristina Zahar, executive secretary of the association.

Many users insinuate that Black and Indigenous women take advantage of their traits to access the professional spaces they have conquered. This is the case of journalists Maju Coutinho, a Black woman, and Alice Pataxó, an Indigenous woman. “Aren't you a monarchist? And that electricity you're using there, bitch? Back there in the [time of the Brazilian] empire, there were no such things,” a profile posted after the journalist published a photo of an Indigenous person taking a picture with a cell phone.

Terms most used to insult women and men

HOW TO ACT IN THOSE CASES

In addition to the violent experience of checking social media every day and finding attacks such as these, journalists also point to the difficulty of denouncing this within the platforms themselves.

Mariliz Pereira Jorge says that she has already reported several attacks, but she did not get any support. The answers she got were that this didn't violated the platform's policies. "A woman who posts a photo of her breast can be banned because it violates the platform's policies much more than the threat of rape, death, as has happened to me and other colleagues." She also believes that aggressions generate engagement.

For Miriam Leitão, each profile should have an individual and/or company, which could be legally identifiable. She suggests that platforms have a responsibility to figure out who is behind the organized waves of attacks, cancel and delete profiles that are not real, because bots (robots) are faceless. “When I get a sexist, lying insult, who can I sue if I want?” she asks.

The monitoring identified that many tweets with explicit aggressive content, such as “bitch” and “slut,” for example, have already been taken down.

Women journalists attacked the most

PLATFORM POSITIONING

In a statement, Twitter reported that it has a policy regarding abusive behavior (which deals with attempts to harass, intimidate, or silence another person's voice) and a policy against the spread of hate (which dictates that promotion of violence, direct attacks or threatening of other people based on specific categories or characteristics is not allowed). If the violation is confirmed, different corrective measures are taken, ranging from the removal and/or reduction of the visibility of a Tweet, to the permanent cancellation of an account.

Regarding the large volume of fake profiles identified as the authors of offensive tweets, Twitter said it has rules to address attempts to manipulate debate on the platform, whether via spam or fake accounts. These rules state that using Twitter services with the intention of artificially amplifying or suppressing information, or engaging in behavior that manipulates or is detrimental to the experience of people on the platform is not allowed. The social network has used machine learning and staff training to identify these profiles. When there is a suspicion, the detected accounts then undergo a so-called challenge (such as email or phone confirmation or entering a Captcha code, for example) to prove that there is a person behind them. If the account does not pass the challenge, it undergoes appropriate corrective measures.

Finally, Twitter reports that it periodically reviews its rules and policies, including its anti-hate policy, to include more categories in what it calls dehumanizing language. The company also stated that it has a Trust and Safety Council made up of 40 organizations and experts in 13 regions, including Brazil.