Dados preliminares de uma pesquisa global com jornalistas climáticos revelam que 60% apresentam sintomas de estresse psicológico. Jornalistas, por sua vez, afirmam que as redações não oferecem suporte adequado.

Laren Aniceto buscou uma terapia de casal para tentar salvar o seu casamento. Ela acabou descobrindo uma série de denúncias contra a sua psicanalista, de manipulação psicológica e estelionato.

Um grupo de pesquisadores analisou os riscos, a censura e as pressões sofridas por jornalistas em 11 países da América Latina. No Colóquio Ibero-Americano de Jornalismo Digital em Austin, eles compartilharam dados importantes sobre a situação na Costa Rica, El Salvador e México.

Estudiosos alertam que a liberdade na região sofre ameaças não apenas de ditaduras, mas também de governos democráticos e por meio do aparelhamento da mídia no Colóquio Ibero-Americano de Jornalismo Digital. Eles pedem por respostas inovadoras e colaborativas.

Mais da metade de um grupo de jornalistas colombianos entrevistados considera abandonar a profissão devido aos baixos salários e à instabilidade no emprego. O estudo também mostrou que os profissionais da imprensa no país não veem a sindicalização como uma forma de melhorar as condições de trabalho.

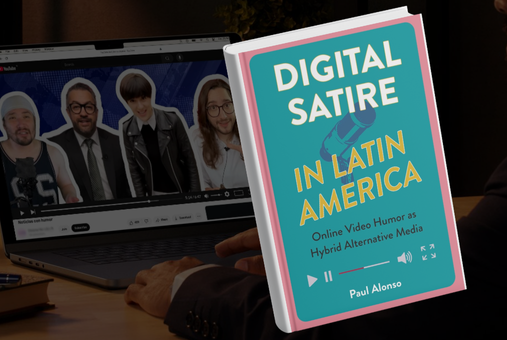

Programas de sátira online, como "El Pulso de la República", do México, ou "La Pulla", da Colômbia, estão ganhando crescente visibilidade e agitando o debate público em seus países, ao mesmo tempo em que preenchem um vazio de críticas sociopolíticas deixado pelos meios tradicionais, segundo um novo livro.

Análise da verba publicitária do Estado na região mostra como leis inadequadas possibilitam que governos utilizem mal os recursos, premiando aliados e ameaçando veículos independentes.

Ao estilo de Trump e Bolsonaro, o novo presidente da Argentina, Javier Milei, emprega uma retórica abertamente hostil à imprensa. Desde que assumiu, esse discurso foi acompanhado por medidas concretas, como suspensão das publicidade do Executivo na mídia. A LatAm Journalism Review entrevistou Santiago Marino, um destacado pesquisador argentinos em políticas de comunicação, para entender a relação do governo Milei com o jornalismo e as políticas públicas de comunicação na Argentina.

A cobertura jornalística sobre clima e biodiversidade não reflete a magnitude da crise enfrentada pela humanidade, mostra pesquisa realizada com jornalistas. Segundo eles, público tem interesse, mas falta de recursos e linhas editoriais dificultam atenção ao tema. Incorporação de tecnologia em redações pode atenuar problemas.

As professoras Celeste González de Bustamante e Jeannine E. Relly, ambas da Escola de Jornalismo da Universidade do Arizona, passaram os últimos dez anos em uma pesquisa de campo, viajando pelo México e entrevistando mais de cem pessoas para analisar a violência contra a imprensa.

O estudo, que entrevistou 1 mil pessoas, tinha como objetivo buscar uma espécie de vacina contra as notícias falsas, principalmente no período eleitoral

Em livro, 21 pesquisadores, a maioria latino-americanos, abordam a falta de pluralidade de mídia e de vozes no discurso público e o seu impacto no processo de democratização