Alma Guillermoprieto has spent most of her professional life paying attention to things from which most people would rather look away.

Since the early 1980s, Guillermoprieto has reported on culture, power and violence across Latin America, primarily for The New Yorker, The New York Review of Books and National Geographic. Her books—including “Samba,” “The Heart That Bleeds” and “Looking for History”—bring together some of her most enduring work.

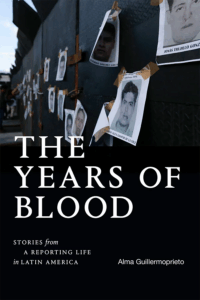

In her latest collection, “The Years of Blood,” published last year by Duke University Press, her deeply reported stories trace the origins of some of the most consequential political transformations this century: the dictatorship of Daniel Ortega and Rosario Murillo in Nicaragua; the budding dictatorship of Nayib Buquele in El Salvador; and the now seemingly ousted regime of Nicolás Maduro in Venezuela.

Her stories provide the relief of insight: She turns events that seemed like disjointed headlines into intelligible characters and narratives, like a relative moving through a darkened house, turning on the lights one by one.

In this interview with LatAm Journalism Review, the Mexico native Guillermoprieto, 76, reflects on her reporting and writing process, the impossible risks faced by journalists across the region, and the experience of reporting long enough to see governments fall, rise and fall again. It has been edited for length and clarity.

"The Years of Blood," Duke University Press, April 2025.

LJR:You write in the prologue that this most recent collection is in large part about disillusion and broken futures. Why do you say that?

Alma Guillermoprieto: Because the disillusion with democracy is something that we are seeing every day. The outstanding case perhaps is Nayib Bukele in El Salvador. The things the transition to electoral democracy was supposed to provide failed people’s expectations, so the broken dream about democracy is as much the populations’ as it is mine.

LJR: For you personally, have you experienced disillusionment? I'm thinking about how you covered the Sandinista Revolution in Nicaragua in the late 1970s, and now you’ve been reporting on it long enough to see the very people from that revolution more or less become the same perpetrators they themselves unseated.

AG : Of course. I think the most meaningful stories to write have been the stories about the Ortega-Murillo binomio because, for me, Nicaragua was the possibility of a good turnout for our politics, and that has proved to be an elusive goal. And in Nicaragua, particularly, of course I feel it because I was there from the beginning, but it's also very rich material for thinking. Why do the left’s best hopes come apart in such dramatic ways? We're seeing it right now with Chile, a leftist administration that gets elected and leads immediately to a right-wing counter. What is the problem in institutionalizing radical changes to benefit a majority of the population? That, for me, is the great question.

LJR : In reading the last story in the collection, about the abduction of 43 students from the Ayotzinapa school in Iguala, México, I was personally left with two big conclusions. The first was that Mexico may never know what happened to those students, and the second is that the case going unpunished may be as big of a tragedy as the abduction itself. What blew my mind was how you connected the dots in a way that nobody else had. How did you choose how much political and historical context to give to a reader who may never step foot in Mexico?

AG: Let me say first that there has been so much brave and astonishing reporting done on this story by Mexican journalists working for small Mexican media and also for El País in Spain. Mexican journalists have been on this case from the beginning, but they don't have the space to tell the story from beginning to end. And I was very aware that I would have the space to lay out the story more narratively, and that was something that I could contribute.

LJR: And in laying out that narrative, how did you choose how much history to give without burdening a reader who is completely out of context?

AG: I don't know if readers could manage to get through it. I tried my best. I thought that context was indispensable. Otherwise, we're just telling the same old stupid tragedy over and over again. I also tried to do two things: to concentrate on three of the parents so that it also became a personal story. And, because the story has been so manipulated and gone over and sifted, I tried to take my facts from the official documents of the investigations that the parents trusted. You'll see that, as far as the facts of the case are concerned, the vast majority of the information comes from those investigations.

LJR: Could you give our readers a little bit of a behind the scenes of your process, if there's a step by step of how you translate Latin America to readers in the United States and the English speaking world?

AG: The first thing to say about that is that I am Latin American and most of what people in the U.S. read is in fact written by non-Latin Americans, and so I tend to use Latin American sources perhaps more than U.S. reporters might because that's what I feel most comfortable with and what I feel I can trust as being more historically informed. I’m also aware that I'm writing for a U.S. audience, and this is helpful to me because it allows me to tell the story assuming complete innocence on the part of the reader. It’s much more demanding, but when I teach workshops, I always say you want to make your readers feel like a five year old who's being taken to the zoo.

LJR: Interesting. Why do you choose that analogy?

AG: Because you want to tell the child what's going to happen and where we're going so the reader feels safe. Then you want to point out the different things that are important, the different protagonists that are important and what is important about them. And then you also want to say, and now we're going to leave so that your five-year-old child with his popsicle safely in hand doesn't suddenly say, “What? I don't want to leave yet!” You want to conclude that story to that person who is reading you from a position of innocence. The interesting thing about that is that if you do it thoroughly, five, 10 or 20 years later, the story will be as interesting to, let's say, Mexicans or Nicaraguans as, I hope, it was to readers in the U.S. because the past is another country.

LJR: What do you mean by that?

AG: The complete quote is: “The past is another country, they do things differently there.” By the time time has gone by, Nicaraguans don’t know what happened.

LJR : You've also said that you view your work as translating Latin America to Latin America.

AG: That's what I mean.

LJR: So is this all part of the same process that you're walking us through or is it a different exercise?

AG: No. If the visit to the zoo or the museum or the natural park is successful, then everybody will be able to read it and get some sense of place from it, or be able to start asking questions that come from a more informed place. It's not my responsibility to answer questions. I think it's my responsibility to generate questions. If I were answering questions, a story would be out of date in six months.

LJR: There was a question I wasn’t going to ask, but you touched on. I wonder how being Mexican and being American has enabled you to do your work.

AG: Well, obviously, because I'm bilingual. This has been an enormous advantage professionally, but also personally in terms of being able to step outside and see the story from some remove, but also be completely inside of my reporting. And the other thing is that I was trained for two years by the Washington Post very much in the traditions of U.S. journalism. Those two years that I spent at the Post were indispensable for the kind of work I do. I follow those standards. And there are different standards everywhere in the world. I was writing for the Guardian before and The Guardian has less respect for the procedural relationship to the U.S. government. They're less reverent about the sacredness of official statements. And as a Mexican, I also am utterly unable to believe anything an official tells me. That's very different from U.S. reporters.

LJR : You’re saying U.S. reporters are more likely to take what the government says at face value?

AG: In good faith, yes. People in the U.S. are brought up, although this may be changing, people have been brought up to trust their government.

LJR: In the story “In the New Gangland of El Salvador,” you give your readers a clear picture of how life was challenging in the country in 2011 because of how gangs were thriving. And then in a postscript, you update the reader about how this situation has been completely transformed under Bukele. Did you work with local journalists in being able to report the story? Is there a story behind the story of how local journalists in El Salvador helped you?

AG: Yeah, absolutely. I don't think I could have done any of the stories I've written without the help of local journalists. I don't think any of us who do foreign reporting could do so without the help of local journalists because realistically, I go to El Salvador and I'm there, if I'm lucky, for a month. How on earth could I possibly understand where to begin even looking for what's important without the help of my colleagues? In the case of El Salvador, it was concretely the journalists at El Faro, which is an online publication that is currently in exile because the government of Bukele cannot tolerate its presence. Those are some of the best reporters in the world doing some of the best reporting in the world. And so when I wanted to know where to start looking for this phenomenon of the violence of the maras, obviously, I went to El Faro. Where else would I have gone? What information would anyone else have that was half as competent, brave and imaginative as the work they were doing? So yes, it was indispensable. And why my colleagues are willing to be so generous with their help is a mystery to me.

LJR: How does that collaboration typically work?

AG: There are various ways. One is that you can hire a local journalist at some approximation to U.S. rates, which are so much higher than what a local journalist might earn, to be what is called your fixer. And so the fixer, in exchange, makes appointments and deals with logistics and talks to you. It's an exploitative relationship, unless they happen to think that by talking to you they're learning something themselves. And then there is also colleague solidarity. And also in many cases, and this was certainly true in the early days in Central America, when local journalists could simply not say what they knew. And so in order to get it said, they relied on foreign journalists to write those stories.

Because I've been around for so long, I know a lot of these journalists, and I knew a lot of these journalists even when they were starting out or they were in a workshop that I taught. So I do have a network of journalists who like me or trust me. And that's always incredibly helpful. Sticking around has its huge rewards. If I were a traditional foreign correspondent, I would have been stationed in Central America and then I would have been transferred to Germany and then like that. So what I have is 40 years of built up experience.

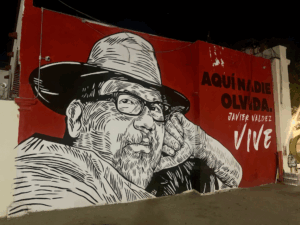

Mural of the Mexican journalist Javier Valdez in downtown Culiacán, Sinaloa. (Photo: Jorge Valencia)

LJR: You write about the murder of Javier Valdez, a very well known local journalist, in Sinaloa in 2017. In a region where we see so much violence against journalists on a near daily basis, what do you think made Javier’s case stand out?

AG: The story about Javier Valdez is in some way the second part of an initial story about local journalists working in Latin America. “Risking life for truth” is a story I wrote in 2012 with the help of my colleagues in Mexico. At the time, the Committee to Protect Journalists had this very strict criteria that if journalists were in any way connected to the drug trade, they couldn't be considered victims. And I was trying to explain the context in which a Mexican journalist works. For me, discovering that context was really enlightening, understanding that these journalists were literally damned if they did and damned if they didn't collaborate. Journalists in the provinces in Mexico negotiate constantly what they can say and do. And they negotiated either aware of, or in an implicit acuerdo, with the local drug trade, which is what diplomats do, by the way, and what many politicians in the world do: constant negotiation between certain forces of evil and themselves to make coexistence and their own survival possible. So that was what the first story was about. And then when Javier was killed, it seemed obvious to me that I had been waiting for that news all along…

LJR: Really?

AG: … because it was clear in retrospect that he couldn't possibly survive. He made his own negotiations and agreements. And somehow he crossed that line by talking about El Licenciado, and he was killed very quickly after that. But again, it was a case of somebody who for no good reason was just insanely generous to all of us foreign correspondents or Mexico City correspondents who showed up.

LJR: How so?

AG: He would tell you not everything he knew. He would point you in the right direction. He would make introductions to people who could be helpful. For example, it was at a time when I was doing a lot of drug reporting and one of the efficient ways to do it was to get into prisons. And so I'd been in the prison in Juarez, which was a stroke of luck and generosity on the part of the people who helped me. Then, I wanted to get into a prison in Sinaloa, and Javier made the introductions to the officials who could make those doors open, and that's how I wrote another story in 2010, which is called “Troubled Spirits.” It couldn't have happened without Javier’s help.

LJR: For people who don’t know about Javier, who was he and why did he become so emblematic? You go to Culiacán, and there are murals of him.

AG: It’s strange how somebody touches people’s lives. There are murals all over Bogotá of the comedian Jaime Garzón, who was murdered in 1999. And Javier touched people’s hearts, too. Javier was a very good investigative reporter and one of the co-founders of an online publication called Ríodoce. They did very rigorously sourced and daring reporting, always walking that very thin line of what they could say without getting themselves killed. And Javier, there were two things about him that stood out. He had an enormous personality. He had tremendous joie de vivre. He loved his life. He loved his family. He loved going out to drink with his buddies. He loved conversation. And he was a terrific writer. So all of this made him well known in Culiacán and delightful to be with, and he was also insanely brave and all of us admired that. So when he was killed, it was an event for the world of journalism. And it was a great loss for reporting in Culiacán, even though Ríodoce continues its very brave work.

LJR: How do you see that the U.S. news interest in Latin America has changed over the last 10 years, especially with the U.S. government's renewed interest in the region under the two Trump administrations?

AG: News coverage changed on Sept. 11, 2001. At that point, we all knew we could just close our notebooks and put away our laptops, and we weren't going to get a story in any publication anytime soon. World attention shifted to the Middle East, and it's never completely recovered. So that was the big gap.

You know, it's amazing that the United States shares a continent with something like 600 million people, and we are not a source of interest for journalistic coverage. This has changed during this Trump administration because even though he promised to do exactly the contrary, he turns out to be kind of a warmonger. And what he is doing in Venezuela and the threats he has made in Colombia and Mexico and the deals he's struck with Bukele and the support he's given Javier Milei in Argentina – all of this has renewed interest in Trump's policies towards Latin America, I would say, more than in Latin America itself.

LJR: Why do you think it's so important to make that distinction?

AG: Because it's the difference between being interested in your own country and being interested in other countries with other languages, other problems, other cultures that are directly influenced by your own country. So how long will this interest last? I don't know.

LJR: Would it be fair to paraphrase that to say that U.S. audiences right now aren't necessarily that interested in Latin America, but rather that they continue to be interested in themselves and in their own country?

AG: Yes, that would be. And I would say that that has always been the case since I've been a journalist. Central America was important because it was part of Reagan foreign policy. And my task, as I've seen it, has always been to tell stories that are compelling enough that readers will read them for the value of the story.

LJR: Somebody said that your work is telling the stories of Latin America on their own, not Latin America as a function of the United States.

AG: Yes, exactly. Sometimes I'm asked about what I think about this person or that administration or that policy. I don't think about it. I think about this world as its own world and as my world. And that's what I try to tell stories about.

LJR: And how do you answer the perennial question editors in New York or Los Angeles or wherever ask about why does this matter to U.S. audiences? Why should I care?

AG: It's not a stupid question. It really isn't. It's just not my question. My answer is to tell the story so that the story is compelling, so that a reader isn't saying, “Oh, what do I want to know about Honduras?” Instead, so that a reader is saying, “Wow! look at this crazy thing that is going on in Honduras!” I was very, very lucky in having Bob Gottlieb and John Bennett as my editors at The New Yorker, all they wanted was a story. And all Bob Silvers at the New York Review of Books ever wanted was writers who could say things that provoked questions.

LJR: How do you expect that U.S. news interest in Latin America may change now after the U.S. operation to remove Nicolás Maduro from Caracas?

AG: My answer would be that barely three weeks after the event, Venezuela is already off most news sites' headlines, overtaken by the threat to Greenland and the rage in Minneapolis. Things that happen in Latin America, no matter how important or devastating, take place far from the established centers of power. It’s one reason why we remain both forgotten and “exotic.”