By FLIP (Colombian Press Freedom Foundation) - Originally published on its website and digital magazine.

This text compiles some excerpts from issue #4 of the magazine Páginas para la Libertad de Prensa by the Fundación para la Libertad de Prensa de Colombia (FLIP, by its Spanish acronym). In it, FLIP analyzes the four-year term of President Iván Duque, who will transfer power on Aug. 7.

"Should be hard lies". With this phrase, President Iván Duque closed the interview with journalist Stephen Sackur of the BBC of London, who directs the program HARDtalk for that channel. For twelve seconds the camera zoomed out, recording a close-up shot of Duque looking distrustfully at his interviewer. The scene contains so much tension that it seems much longer. It is an instant that could summarize the four-year relationship between the outgoing government and the press that was not on his side: defensive, most of the time; hermetic, depending on the strategy, and, on some occasions, hostile.

In the interview, Duque said that in 2021 the country recorded the lowest number of homicides in the last forty years. This was a false figure, as he was reminded by the ColombiaCheck fact-checking portal, which warned that the 2021 homicide figure was the highest in the past seven years. Despite the fact that the interviewer knew about this and refuted him, Duque insisted on repeating the data he had already given in other interviews and accused the journalist of being a liar.

A reconstruction of the relationship between Duque and the media shows that the recipe was based on the binary distinction friend-or-foe. With those considered enemies he built an unbreakable wall, preferring self-interviews to questions he anticipated to be uncomfortable. At the same time that he distanced himself from information he could not control, he was in charge of enlarging his own communications machine. According to figures the Presidency gave via an open records request, in 2018 the Presidency's communications team was composed of 15 people, while currently there are 54.

And not only did he expand his team, he also invested more than 45 billion pesos [about US $10,450,000] in official advertising, taken from public funds, to improve his image and create a parallel narrative. In its advertising contracts, he sought to monitor the media, configure social media users and, ultimately, position his name and image in social media, especially in times of crisis such as the social unrest protests and the pandemic.

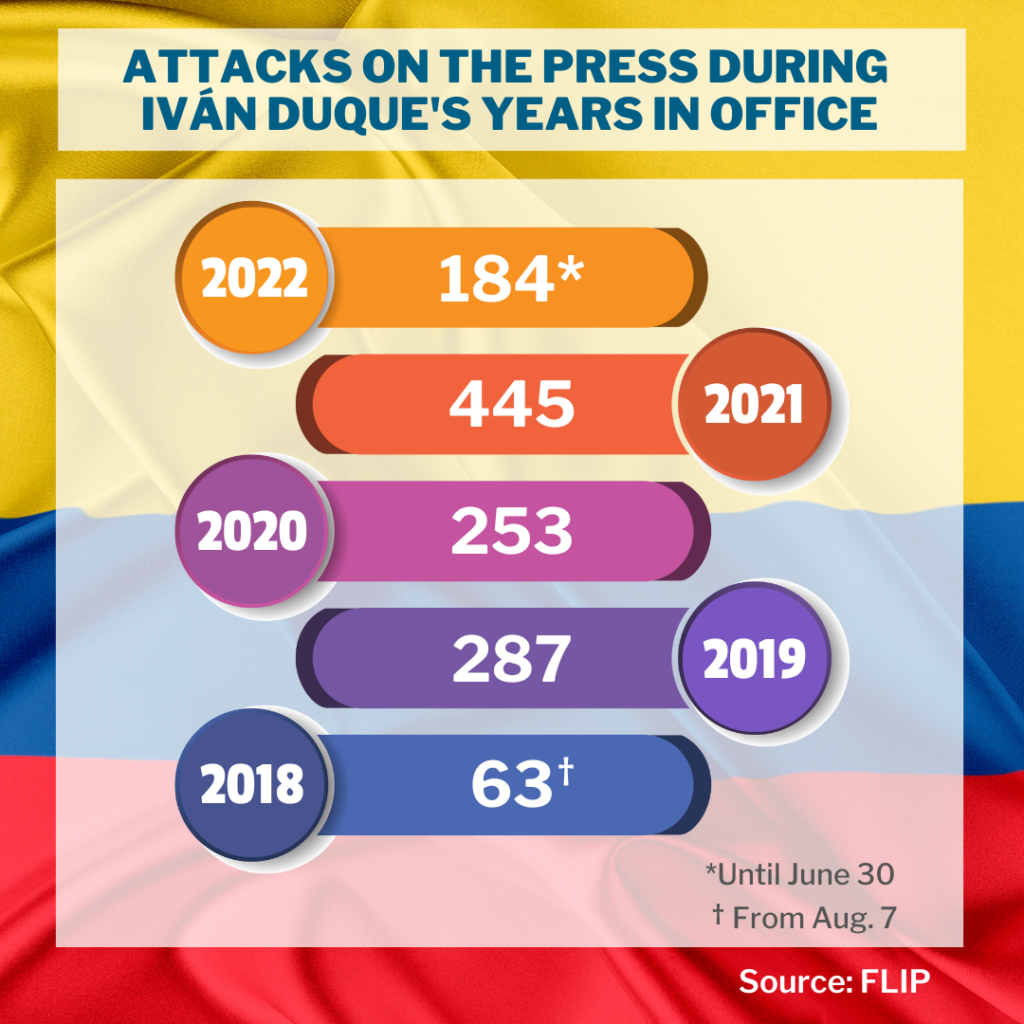

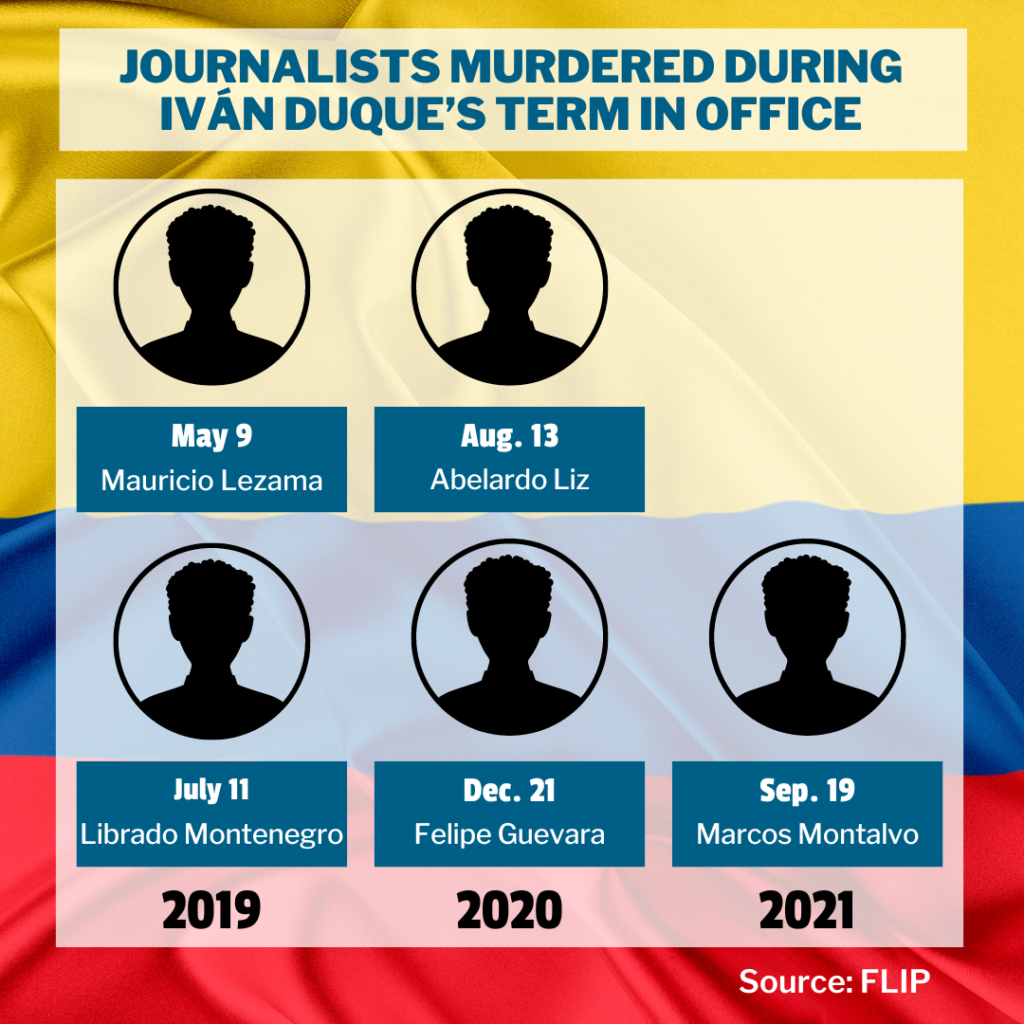

All this happened while violence against the press intensified: in Duque's four years, there were more than 750 threats to journalists in order to censor or intimidate them; and five regrettable murders of journalists in order to silence their investigations and denunciations.

This four-year period yields a very discouraging balance for the press: from Aug. 7, 2018 to June 30, 2022, FLIP recorded five homicides against journalists because of their profession and 628 threats against media and journalists. The violence is, in part, linked to the armed conflict that has been increasing during these last years and the illegal armed groups that threaten and harass journalists. But it’s also due to an opaque government management, and because of officials and members of the security forces that attacked and hindered the work of those who tried to cover them.

In total, in these four years, we recorded 1,232 violent attacks against the press. In 486 cases, the identity of the aggressors is unknown. Law enforcement agents (302) are the second largest violent attackers of the press, ahead of private individuals with 207 cases, members of criminal gangs with 77 and dissidents with 61.

In total, in these four years, we recorded 1,232 violent attacks against the press. In 486 cases, the identity of the aggressors is unknown. Law enforcement agents (302) are the second largest violent attackers of the press, ahead of private individuals with 207 cases, members of criminal gangs with 77 and dissidents with 61.

The coverage of issues related to public order, the management of local administrations and the national government, social protest, elections, environment and health were the most sensitive issues related to violent attacks against journalists and with greater frequency in Bogota (314 aggressions), Antioquia (143), Valle del Cauca (100), Arauca (97) and Santander (57). During the four years of Duque's presidency, there was an increase of 182 cases of threats, displacement and exile in these regions, compared to the previous four years.

The aggressions during the two big days of demonstrations in 2019 and 2021 point to a historical peak. From Jan. 1, 2019 to June 30, 2022, FLIP recorded 511 attacks on the press while covering demonstrations. Only in the three months of the National Strike of 2021, FLIP documented more than 340 attacks and registered as the main aggressor members of the National Police, with a high level of impunity. Of the 25 cases of aggressions against journalists monitored by FLIP where the aggressor of the public force is fully identified, only eight legal cases are active.

Digital violence aimed at silencing the press has also increased in recent years: from Aug. 7, 2018 to June 30, 2022, FLIP recorded 248 threats and harassment against the press in digital environments, mainly through social media and WhatsApp, which represents 39% of the total threats recorded in this period.

Online violence has been characterized by coming mostly from fake profiles. In this environment, women journalists are the most affected by gender-based violence, such as harassment, sexist and misogynist comments, and smear campaigns in social media.

While violence against the press increased, the government's protection actions weakened. Although President Duque in his first months in office announced the reengineering of the National Protection Unit (UNP, by its Spanish acronym) as part of the Timely Action Plan (PAO) to, as he said: articulate, guide and coordinate the different protection programs, resources and responses of the different entities around the protection of leaders, human rights defenders and journalists, this ended up focusing on changes in form but not in substance. Prioritized factors such as context analysis, gender mainstreaming and transparency in the decisions made by Cerrem [UNP's Committee for Risk Assessment and Recommendation of Measures] were not taken into account, nor were those warned about by social organizations.

Not only were there setbacks in the evaluation and implementation processes of the UNP, its credibility fell increasingly due to the violation of the protection of personal data and privacy of protected persons. At the beginning of 2022, the installation of technological devices, such as GPS, in the vehicles assigned for the protection of journalists became known. An action that the UNP justified, without much detail, as a measure to ensure the proper functioning and management of the protection schemes.

Not only were there setbacks in the evaluation and implementation processes of the UNP, its credibility fell increasingly due to the violation of the protection of personal data and privacy of protected persons. At the beginning of 2022, the installation of technological devices, such as GPS, in the vehicles assigned for the protection of journalists became known. An action that the UNP justified, without much detail, as a measure to ensure the proper functioning and management of the protection schemes.

This monitoring, without the express authorization of the data owner and without clarity on the handling and use of this information, produces a breach of trust that affects the functionality and purpose of the protection measures.

The figures and testimonies show how the president ignored the recommendations and calls to promptly and effectively address the security situation of journalists. Also, there was no support for the work of the press from the national government in such critical moments as the social demonstrations. Finally, Duque ends his mandate leaving Colombia among the four most dangerous countries to practice journalism in Latin America, according to Reporters Without Borders.