Elizabeth Salazar and Carla Díaz are two Peruvian journalists who specialize in covering a gender and human rights agenda. After working together on a journalistic project in which they analyzed how the media has portrayed LGBTQ+ people in recent years in Peru, they began to ask themselves certain questions. They confirmed that there is a negative representation of this population in the media, and wondered how the judges who decide the rulings for sex and name change in the identity documents of trans people were acting. Thus was born Identidades negadas [Identities denied], a feature story — published in Agencia Presentes, with the support of the Canadian Embassy in Peru — that analyzes the violent and discriminatory discourses that sustain 208 of these rulings in the last decade in the Andean country.

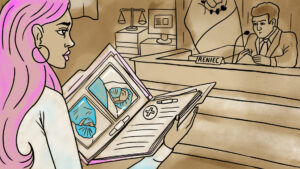

Peruvian journalists carried out an investigation that makes visible the discriminatory and violent discourses that sustain the rulings for name and gender change of trans people in Peru. (Illustration credit: Dariana Castellano)

To understand Salazar and Diaz's working method for this story, one must first understand the context of gender identity in their country. Unlike other countries in the region, Peru does not have a gender identity law. In order for a trans person to make changes to his or her identity document, he or she must do so via the courts. As shown in the feature story, this implies that trans people who wish to have an identity document in accordance with their self-perceived identity must undergo physical and moral scrutiny by judges and prosecutors of the National Registry of Identification and Civil Status (Reniec, by its Spanish acronym).

The journalists wondered how many trans people have tried or have managed to access this right in Peru, and what happens when their cases reach the Judiciary. "We saw that there was no in-depth analysis available. We had this idea that the cases we knew about were not isolated facts, but rather it was something systematic," the authors told Latam Journalism Review (LJR).

"We started from the hypothesis that there were discriminatory and violent elements in the rulings," Salazar said. To prove it, "We had a plan A, B and C; and a lot of trial and error. In order to obtain rulings for sex and name changes during the last ten years, they made access to public information requests. But since the official statistical registry does not include the category of gender — it only identifies plaintiffs by the name they were assigned at birth — it was not possible to get what they were looking for in this way.

Plan B was to approach lawyers who accompany the processes of name and gender change in the identity documents of trans people. "We heard from ten lawyers who told us that no one had been able to expose these cases. To them, so far, they were just isolated cases. But we couldn't do the project with a sample of ten," Salazar said.

Finally, plan C was "to go to the foundation of data journalism, [that is] to download the information. Each name change is announced by edict in the official gazette. We downloaded all the edicts that contained name change requests by a Peruvian citizen. We found more than 1,800 results, it was huge. We ran it through a filter to disqualify people who were not LGBTQ+," Salazar continued. "Then, we had to review it manually to find out if they were trans people. Using this filter we were left with a smaller group. But we had to log into the Judicial Branch search engine to confirm, one by one, that they were indeed trans people." This is how they arrived at the 208 first and second instance rulings in courts and civil chambers that they analyzed for their story. This research phase took them two and a half months.

To work with the material, "we developed a matrix of discourse analysis. We analyzed rulings and records of hearings in which there were elements that violated the lives of trans people," Díaz said. She added that, for the analysis, they relied on international human rights standards such as Advisory Opinion 24/17 of the Inter-American Court of Human Rights, which addresses the right to equality of LGBTQ+ people. This opinion places special emphasis on how the recognition of gender identity and expression should be respected.

The authors stated in their article that "85% (176) of the 208 sentences analyzed showed a pattern of arguments that harm the rights of trans people, by demanding stigmatizing requirements or ignoring the legal framework and the concept of gender identity." They even detected this treatment in the claims that were considered well founded, which were 83% of the total reviewed. They then grouped the most frequently used discriminatory arguments against trans people in the rulings into five types. These were: accepting or demanding from trans people evidence of undergoing body surgeries or hormone treatments; pathologization (allowing psychological and psychiatric reports to be presented as evidence); comments or speeches that perpetuate gender stereotypes and discrimination; rejection of the legal framework that allows the recognition of the name and gender identity; and ignoring the concept of gender identity.

Peruvian journalists carried out an investigation that makes visible the discriminatory and violent discourses that sustain the rulings for name and gender change of trans people in Peru. (Illustration credit: Dariana Castellano)

When it came to telling stories with a human rights perspective, journalists were presented with the challenge of how to expose information and discourse analysis without re-victimizing or re-exposing the victims. "The main challenge is, how do I tell the story without it sounding like a horror movie," Salazar said. For this reason, one of their options was to use illustrations in the article, rather than photographs, which the authors believe entail revictimization.

Another of the lessons learned by the journalists was to "break down the paternalistic approach and gaze the media has towards LGBTQ+ people." Salazar added: "LGBTQ+ people have a voice, authority and a life beyond the media stereotype. Trans people want to change the name on their documents for very particular reasons. Many have jobs in an office environment, or study at a university and do not want to be harassed. It’s necessary to tell the story of the lives of LGBTQ+ people as we tell the story of anyone else's life."

For her part, Díaz emphasized that "when working with vulnerable populations, it’s important to protect the identity of individuals and cases." To better explain this, she offers an example: "There are judges who are allies, who process gender change requests. Lawyers already know which courts to go to for name and gender changes. We know which are the places where most cases are approved, but we don't mention it. We had to refrain from doing that because there’s a precedent that, when this information is made visible, Reniec denounces or takes action against those judges and lawyers."

For Díaz, it is very important to understand that "In human rights journalism, we are doing something for a reason. We have to think about how we approach these problems. The focus from the beginning was not to expose LGBTQ+ populations, but those who infringe on them. Not everything is permissible.”

Another challenge highlighted by the journalists was their mental health care, an aspect they did not foresee in their research. "There were times when I was reading what Carla was processing, so many rulings and with such strong arguments, that I had to close the computer because it made me nauseous," Salazar said. "We underestimated our own mental health care. We had both dealt with the gender issue, but this was different because these were arguments coming from an authority figure, firm rulings. Something systematic and massive. But because of deadlines, there was no time to process it, and we did not schedule it." The authors were in agreement that, for future research, they will make room for conversations on mental health care.

--

Contributor Florencia Pagola is a freelance journalist from Uruguay. She does research and writes about human rights and freedom of speech in Latin America