“It is necessary for the magic lens/to enrich the human vision/and the reality of each thing/a drier reality to extract/so that we penetrate deeply/into the pure enigma of images.” Carlos Drummond de Andrade, one of the greatest Brazilian poets, wrote these verses in dedication to Evandro Teixeira, one of the country's greatest photojournalists, who died at the age of 88 on Nov. 4 in Rio de Janeiro after battling leukemia for more than 10 years.

In a career that lasted more than seven decades, almost 47 of those years at the now-defunct Jornal do Brasil, Teixeira documented Brazilian public life with the best journalism has to offer: audacity, urgency, attachment to reality, challenge to any kind of authoritarianism, a commitment to democracy, care, zeal and creativity.

His best-known work focuses on the military dictatorship in force in Brazil from 1964 to 1985, of soldiers and tanks in the streets, of protesters against the regime, of the workings behind the scenes of power and of the daily life that went on amidst the political turmoil.

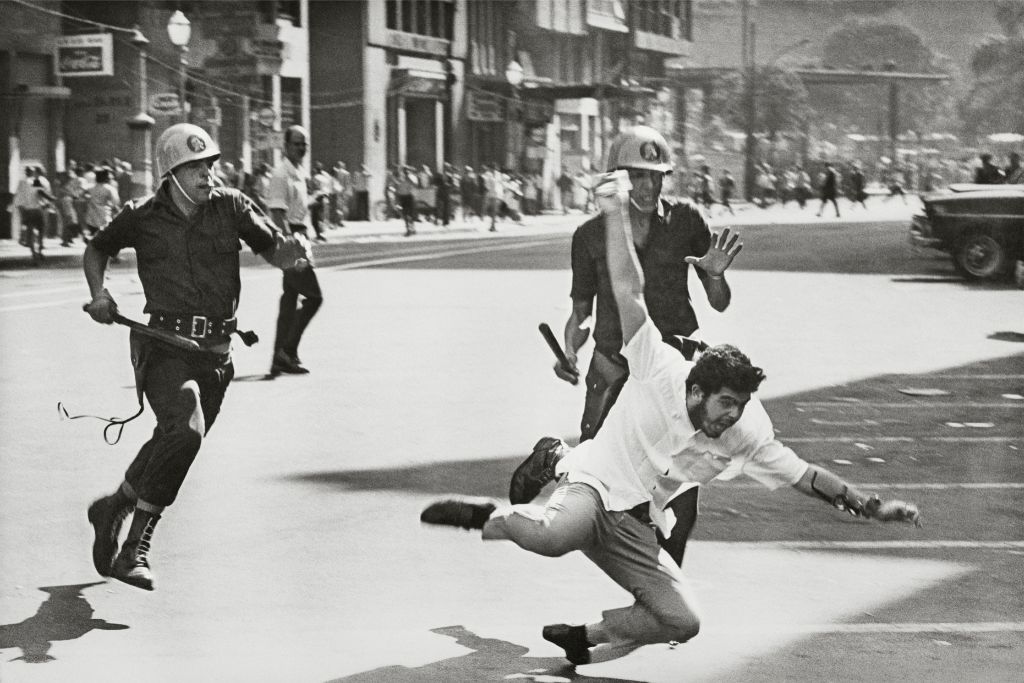

One of Evandro Teixeira's most famous photos, in which soldiers knock down a student running in protest in Rio de Janeiro on June 21, 1968 (Photo: Evandro Teixeira/IMS Collection)

Portrait of Evandro Teixeira in Rio de Janeiro in 2013 (Photo: André Arruda/Instituto Moreira Salles)

His work, however, goes far beyond these records. Teixeira also took photographs of countless personalities from Brazilian and global cultural life, of anonymous citizens in fortuitous and poetic moments, of historic events in other countries, of urban tragedies, of sports and fashion, among others. His death had great repercussions in all the main newspapers and media outlets in Brazil, which unanimously hailed him as an indispensable reference in the history of Brazilian photojournalism.

In an interview with LatAm Journalism Review (LJR) in 2023, Teixeira attributed his success to some essential elements: luck, effort and courage. “What helped me most in my career was luck, as well as the desire to do the work,” Teixeira said. “I always believed that I could make the stories work, and I never had respect for the crazy actions of those in charge.”

A candid portrait of Brazilian musical legends: Chico Buarque, Tom Jobim, and Vinicius de Moraes share a lighthearted moment, lounging across a table (Photo: Evandro Teixeira/Instituto Moreira Salles Collection)

The son of a farmer and a housewife, Teixeira was born in Irajuba, a town in the interior of Bahia, a state in northeastern Brazil. His first photographs were taken with his uncle’s camera, which he used to capture family members and animals.

In 1950, at the age of 15, he went to live in Jequié, where he bought his first camera and worked as an intern at Jornal de Jequié. He then moved to study in Ipiaú, where he worked as an intern at Jornal Rio Novo and bought a Polaroid – later, he would adopt Leica as his preferred brand throughout his life.

In 1954, Teixeira moved to Salvador, the state capital, where he interned at the newspaper Diário de Notícias, which belonged to the Diários Associados group, then one of the largest media organizations in Brazil. In Salvador, one of the lessons that Teixeira considered decisive in his career took place: a photography correspondence course with photojournalist José Medeiros, offered by the magazine A Cigarra.

“The process was very didactic. I learned how to take good photographs in this correspondence course,” Teixeira said about the course in a 2012 interview with Paulo César Boni.

Under the influence of his friend Manoel Pinto, known as Mapin, Teixeira moved to Rio de Janeiro at the end of 1957. The city was then the cultural capital of Brazil, and was experiencing the so-called Golden Years in the wake of the creation of Bossa Nova. The year following his arrival, he began photographing for Diário da Noite and O Jornal, two publications from the Diários Associados group.

In 1961, he resigned and went to work at the weekly magazine O Mundo Ilustrado, directed by Joel Silveira, one of the most renowned reporters in Brazil. He stayed there for ten months, having the opportunity to cover the World Cup in Chile, won by Brazil. At the end of that year, he transferred to Jornal do Brasil, where he remained until the end of the print version of the newspaper in 2010.

When Teixeira arrived at Jornal do Brasil, it was the most prestigious Brazilian daily newspaper. Some of the greatest Brazilian writers and journalists wrote there, such as Carlos Drummond de Andrade, Otto Lara Resende and Barbosa Lima Sobrinho. In 1959, the newspaper underwent an important graphic reform that gave great prominence to photography on its covers and pages.

In the interview with Paulo César Boni, Teixeira recalled the working environment he found at the newspaper:

“Photography was the newspaper’s elite. To give you an idea, at JB the photographer earned more than the text reporter,” he said. “You had the freedom to take to the streets, assign yourself stories, create your articles and photo shoots, and all without a flash or light meter. Flash was banned in Jornal do Brasil. Alberto Ferreira, who was one of the greatest photography editors in Brazil, prohibited it.”

Dragonflies rest on rifle bayonets during a tense moment under Brazil’s military regime, 1968. This powerful image by Evandro Teixeira led to his overnight imprisonment (Photo: Evandro Teixeira / Instituto Moreira Salles)

On the day of the military coup that deposed the democratically elected President João Goulart, on March 31, 1964, Teixeira took some of his most famous photos. He was the only journalist to enter Copacabana Fort, where General Humberto de Alencar Castelo Branco, who would become the regime's first dictator, was stationed.

A friendship gave him his entry ticket: according to what he told Boni, Teixeira played volleyball on the beach on Sundays with an Army captain named Lemos. The friend called him on the day of the coup and invited him to join the fort without identifying himself.

“I accepted it right away. He warned me that he would enter without any problems because everyone knew him, but that I could be stopped. And if I was, he wouldn’t be able to do anything,” Teixeira said. “I decided to take a chance. At the entrance to the fort, the sentry saluted and Lemos responded by saluting and I imitated him. We went in.”

That night, in heavy rain, Teixeira took a photo in which little can be seen other than the silhouette of soldiers, a cannon and bayonets. The image would later be considered a harbinger of Brazil’s dark period.

Another historic image, perhaps Teixeira's most famous, is of a student being chased by two police officers with batons in their hands on June 21, 1968, so-called Bloody Friday, when the police brutally repressed a student demonstration. To this day, it is not known who the young man was, with his glasses in the air, captured in a moment of urgency.

There are also more subtle and poetic photographs, such as “Dragonflies and bayonets,” from 1968, in which insects land on the pointed tips of rifles. The photo was taken after the start of an exhibition of weapons used in the Paraguayan War (1864-1870) with the presence of then-President Artur da Costa e Silva.

The image appeared on the cover of the newspaper the following day, while the photos from the exhibition appeared small inside the newspaper. The editorial choice infuriated the president, who called the photographer for a face-to-face meeting. Teixeira then spent a night in prison.

That was just one of Teixeira's several arrests during the military dictatorship. Another of the arrests was due to a surreptitiously taken photograph of a general in his pajamas during a visit to his home. “During the dictatorship it was like this: arrests, beatings and equipment broken or seized. I was beaten a few times, I was arrested other times. But, fortunately, they never seized or broke my equipment,” Teixeira told Boni.

Many of these images could only be published because Jornal do Brasil was then an influential and powerful publication, under the command of journalists with the courage and space to challenge the censorship in force in the country.

Under the command of editor in chief Alberto Dines, the publication was the main voice among major Brazilian newspapers denouncing the arbitrariness and violence committed by the military regime. According to Teixeira, the former editor, who died in 2018, “was all in. He was not intimidated. And he was very open to talking to journalists and photographers, he was very open,” Teixeira told LJR last year.

Teixeira said that, in the 1970s there were 35 photographers employed at the newspaper, a number considered high for the current average of a large Brazilian newsroom.

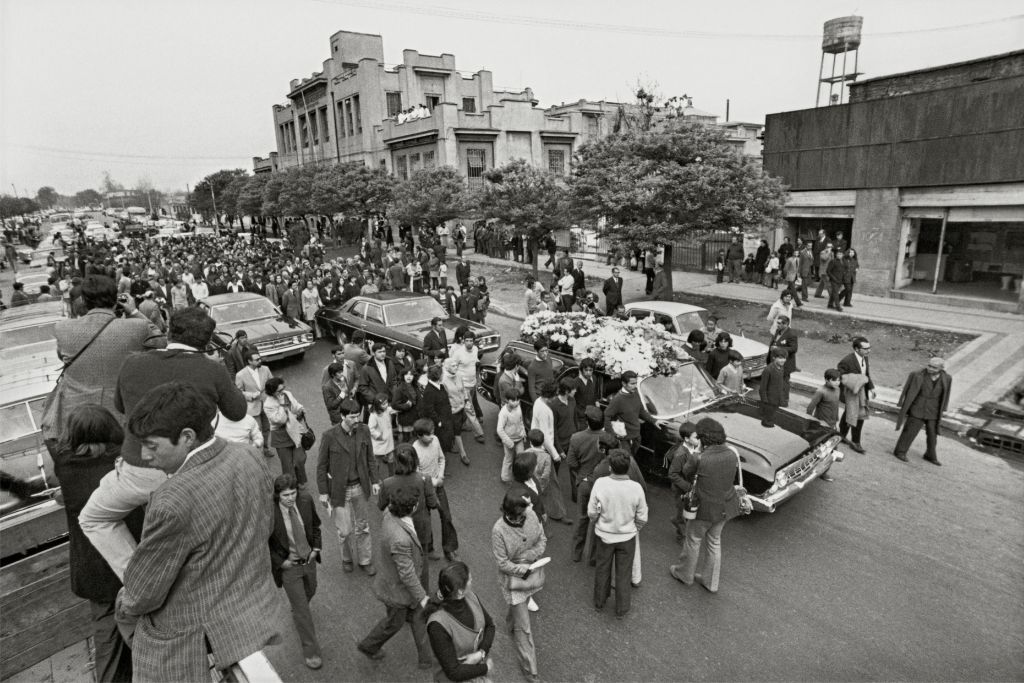

“The newspaper had power. We could travel wherever we wanted,” the photographer said. Some of these trips yielded historic clicks: Teixeira was, for example, the only Brazilian photographer to travel to Chile immediately after the coup carried out under the leadership of Augusto Pinochet on Sept. 11, 1973.

There, he was the only photographer in the world to enter the hospital where the body of the poet Pablo Neruda lay, poisoned by the dictatorship. He also photographed political prisoners and the writer's funeral, which became an act of protest against the nascent dictatorship. “Nowadays, they would probably use photos from news agencies. But it's different when the newspaper uses its own professional, who has the publication's perspective,” he said.

Funeral of Chilean poet Pablo Neruda. On the way to the General Cemetery of Santiago, the crowd grows with popular supporters(Photo: Evandro Teixeira/IMS Collection )

In addition to politics, Teixeira took striking portraits of many Brazilian personalities of the 20th century, such as Pelé, Ayrton Senna, singer Leila Diniz, poets Carlos Drummond de Andrade and Vinicius de Moraes and composer Tom Jobim, among others. He published seven books, the most important of which was dedicated to the centenary of the War of Canudos, in 1997.

His collection of more than 150,000 photos was donated to the Moreira Salles Institute, which last year organized an exhibition based on photos taken in Chile. The photos continue to be the subject of study and exhibitions inside and outside Brazil. In 2008, alongside Sebastião Salgado, Teixeira was one of only two Brazilians to participate in an exhibition at the Leica Gallery, in New York, bringing together 40 international photographers.

“Teixeira was someone who, in his work process, was always committed to journalism as a testimony, to being present in the place of events, with an audacity and boldness that led him to accept no limits to his commitment to quality information,” Sérgio Burgi, photography coordinator at the Moreira Salles Institute, told LJR.

Teixeira also received dozens of awards, including some granted by UNESCO and the Inter American Press Association. The photographer leaves behind two daughters, Carina and Adryana, and three granddaughters.