In March 2022, former Mexican President Andrés Manuel López Obrador called presenter Chumel Torres an “ideologue of conservatism” and accused him of being a voice his opponents used to discredit his government. The president made similar accusations against journalists Carlos Loret de Mola, Héctor Aguilar Camín and Enrique Krauze.

The difference is that Torres is not a journalist or columnist, nor does he work for a traditional media outlet. Torres is a YouTuber widely known in Mexico for his political criticism and satire on the online show “El Pulso de la República.”

The Torres case is an example of the growing visibility and impact that creators of digital satire are having on public debate in the Americas, according to Paul Alonso, a Peruvian journalist, author and academic.

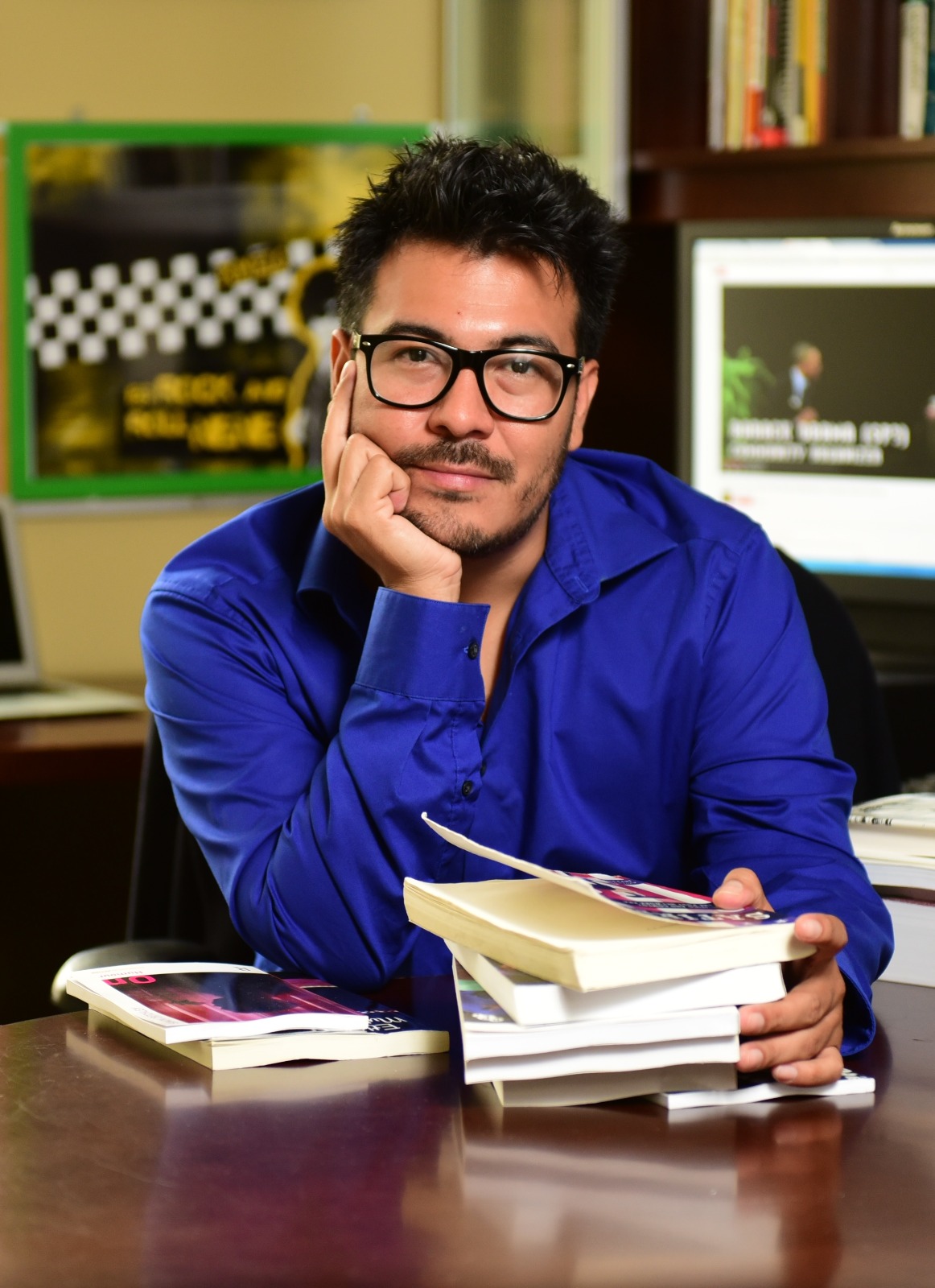

In his new book, Paul Alonso analyzes how online satire has become increasingly influential in Latin America. (Photo: Courtesy Paul Alonso)

Alonso, who is currently an associate professor at the School of Modern Languages at the Georgia Institute of Technology, is the author of several books on satire and infotainment in the media, including the forthcoming publication “Digital Satire in Latin America. Online Video Humor as Hybrid Alternative Media.”

“The fact that the president of Mexico called him – a digital creator – one of his main adversaries, I think was symptomatic of saying ‘okay, the president of a country is really understanding that these kinds of digital independent creators are his main critics and that his voice is very visible,” Alonso told LatAm Journalism Review (LJR).

In this new publication, Alonso, who has previously addressed satire on television and in print media, analyzes how online satire has become increasingly influential in Latin America and among the Latino population in the United States. He also addresses how digital shows of satire and sociopolitical criticism are filling the gaps left by television, traditional journalism and commercial entertainment.

For his research, Alonso conducted interviews with producers and presenters of some of the most influential satirical programs born on the internet in Argentina, Peru, Mexico, Colombia, Ecuador, and among the Latino population in the United States. He also studied each case from the perspective of discourse analysis.

One of Alonso’s key findings is that most online sociopolitical satire programs have emerged as a reaction to moments of crisis, social trauma or growing polarization.

“El Pulso de la República” was established in Mexico in the midst of a marked social divide between what López Obrador considered “the good people” and his adversaries. Meanwhile, in Colombia, political satire shows such as “La Pulla” and the gender-focused show “Las Igualadas,” both from the newspaper El Espectador, emerged in response to the trauma of a long period of political violence surrounding the peace process in that country, Alonso said.

“They approached the issues reacting to the context of the war in Colombia and to the polarization created by the national peace process,” Alonso said. “The same way that, for example, [comedian] Guille Aquino in Argentina reacted to the polarization created within the right and the left, the Kirchnerism and Macrism, and still does some satiric content about the polarization after [President Javier] Milei’s election.”

Online programs like the ones above are characterized, according to Alonso's findings, by putting the spotlight on issues that mainstream media outlets are not covering, or are not fully bringing to light.

“One of the main roles of satire has been – especially in the media landscape – to fill the gaps left by traditional media, television, newspapers, etcetera, which in Latin America have been traditionally aligned with political interests and have been more partisan,” he said.

Historically, Alonso added, social and political satire has had a sporadic presence in Latin American media due to the nature of the genre. The author describes satire as a transgressive, irreverent artistic form that targets power in, in some cases, an aggressive way. For a traditional media outlet, that kind of content can lead to the exit of sponsors and even legal proceedings, he said.

“It has other kinds of rules than the ones of traditional journalism, it can sometimes be a very effective form, very smart and very creative,” Alonso said. “But that also can alienate advertising, or not align with some of the most traditional conservative editorial standpoints of traditional media.”

Chumel Torres was considered by the former president of Mexico as an opposing voice, due to his criticisms in his online show “El Pulso de la República”. (Photo: Screenshot from YouTube)

For these reasons, satirical media and productions have mostly been produced independently, he added.

The impact that satirical programs have had online is due, in large part, precisely to the fact that they address issues that aren’t present in traditional news coverage, Alonso said.

One of the main impacts that the author found in his research is the attraction of young audiences who seek content on topics that other media do not fully address.

“They have created new conversations and attracted new, younger audiences, which was – especially in the period that I covered – a particularly important issue because traditional outlets were really struggling to get young readership, young viewership,” Alonso said.

Sociopolitical satire shows also have the potential to help combat disinformation, Alonso said, which has been especially noticeable during the COVID-19 pandemic and in similar contexts.

As an example, he cited the case of Peru and well-known comedian Gerardo García “El Cacash”, who comments on news in a comedic and dynamic way through his YouTube channel and a podcast. Alonso explained that creators like García dismantled the biased discourses about the health crisis that were reproduced by traditional media.

This type of criticism of the media is another characteristic that Alonso found in most of the digital satire programs he analyzed for his book. He said this type of content plays an oversight role, not only of political power, but also of media.

“Most of the contemporary satire is a criticism of the system, of some of the social vices of a society, but they also do media criticism,” Alonso said. “One of their main targets in most cases is the media of their countries, too. They present themselves as an alternative to the media by also exposing, criticizing, deconstructing the discourse of the media.”

While Chumel Torres absolutely rejects the title of journalist, “La Pulla” defines itself as an opinion journalism program. There is a difference in the types of approach to information that the creators analyzed in Alonso’s book exercised, he said. That is why there is no consensus in considering political satire as a form of journalism.

The author of “Digital Satire in Latin America” interviewed producers and hosts of digital satire shows in Argentina, Peru, Mexico, Colombia, Ecuador. (Photo: Musuk Nolte)

Some satirists shed the label of journalist to enjoy greater artistic freedom, Alonso said. Others argue that they are not journalists because they do not report or generate news, although they do analyze and comment on facts, which, at the end of the day, are also functions of journalism.

“In old traditional media, you have the reporting news section and you have the feature stories section,” Alonso said. “And then you have the opinion and analysis sections. They [creators of satire] do that part of interpreting, commenting and contextualizing.”

Some creators of satire, Alonso said, go even further, reaching into areas such as activism. He cited the example of American comedian John Oliver, whose pieces on corruption scandals at FIFA or the Internet neutrality controversy included calls to action to achieve real-life impact.

Similarly, Argentine comedian Malena Pichot, who throughout her career has starred in online satire shows, such as “Cualca”, has become one of the most relevant feminist voices in her country.

“She is always confronting and engaging with a lot of debates regarding gender issues and women rights,” Alonso said. “A lot of these satirical shows are also platforms for, I would say, a more visible criticism and sometimes even activism.”

Authors cited in the book, such as Geoffrey Baym, see satire as a new type of journalism with particular characteristics. However, Alonso prefers to define this type of content as a new form of sociopolitical communication that is becoming increasingly important in public discourse.

However, he found that several of the creators and producers of satirical content he interviewed for his research had some kind of experience or training in journalism. But they ended up dedicating themselves to satire because it better fulfilled their vocational needs, especially of those who had the desire to practice accountability journalism.

“Many journalists that couldn't find their way in mainstream media, especially the ones that had a vocation for a democratic conversations and watchdog journalism, found a space to do social, and political critique in satirical forms,” Alonso said. “I do think there is a very strong connection between the journalism background and the satirical discourse. The fact that many of these producers, hosts and writers have a professional connection with journalism is very telling of the hybridization of these forms.”