In the Latin American news ecosystem, where polarization and misinformation are increasingly commonplace, it is essential for journalists to be prepared to identify and understand dangerous discourse. This discourse goes beyond hate speech and can incite violence, discrimination or even criminal acts against vulnerable groups.

To address this challenge, journalists must analyze the context and intentions of the sender of dangerous messages, recognize how people's biases and the algorithms of digital platforms influence the spread of disinformation, and keep in mind that the way stories are told has a real impact on society.

These were some of the recommendations shared by panelists at the webinar "Disinformation, audiences and dangerous discourse on diversity issues," organized by the Network for Diversity in Latin American Journalism and held on July 11, with the support of the Knight Center for Journalism in the Americas.

Mariana Alvarado, from the Network for Diversity in Latin American Journalism, moderated the talk in which Daniela Mendoza (Verificado), Edgar Zamora (DW Akademie) and María Teresa Juárez (Pie de Página) participated. (Photo: Screenshot).

Panel participants were Daniela Mendoza, director of Verificado (Mexico); María Teresa Juárez, co-director of the Red Periodistas de a Pie (Mexico); and Edgar Zamora, expert in media and information literacy of the DW Akademie (Guatemala). Mexican journalist and co-founder of the Network, Mariana Alvarado, served as moderator.

The following are 10 key issues mentioned by the speakers that journalists should consider in order to counteract dangerous discourse and the disinformation it generates.

Journalists must be prepared to identify dangerous discourse in order to avoid the consequences of this type of narrative.

According to Mendoza, dangerous discourse is any message broadcast through any media, aimed at a vulnerable group due to issues intrinsic to the people who are part of it, such as race, religion or sexual orientation, among others, and which incites violence, discrimination or criminal acts against such groups.

While many journalists are aware of what hate speech is, there are other types of dangerous speech that, while not hate speech, can lead to hate speech.

"Dangerous discourse can be hate speech when it includes imminent incitement to crime. That is, when it calls to act against a group or promotes taking away a group’s rights, or hinders the life of a group because of discrimination," Mendoza said.

The journalist was clear in saying that these types of narratives are not supported by freedom of expression, as it’s discourse that affects the physical integrity and rights of other people.

"Freedom of expression has its margins. Its margins are personal honor, national security and hate speech," he said. "Freedom of speech has limits when it reaches hate speech."

To detect whether a message constitutes dangerous discourse, it’s necessary to analyze the context in which it’s given. This includes identifying who delivers it.

"When we talk about hate speech, we have to take into account the speaker’s influence. That is, the position in which they find themselves and whether this person has the opportunity to influence other people," Mendoza said.

It’s possible that the author of dangerous discourse aims to create disinformation to re-victimize, discriminate or stigmatize a person or group. It’s therefore essential to recognize these signs in time to help prevent this discourse from spreading.

The close link between dangerous discourse and disinformation lies in the fact that the latter appeals to people's biases. That is, to their set of beliefs, which are commonly based on stereotypes and stigma, panelists said. Those stereotypes and stigma become disinformation because they appeal to the emotions of a set of other people who share the same biases.

Stigmas and stereotypes about a group of people easily turn into misinformation because they appeal to emotions, the speakers said. (Photo: Screenshot from Verificado.mx)

These biases take on a greater dimension due to the algorithms of digital platforms, especially the so-called "confirmation bias," which Juarez defined as the tendency people have to search for information that matches their way of thinking.

"If I search for a certain topic, obviously the algorithm in all my searches is going to return information that is akin to how I think," she said. “We have an issue to watch out for so we can have a contextual reading that can shed light on how to solve or offer creative responses to such a sensitive topic.”

Zamora added that with the development of artificial intelligence and its role in creating disinformation, journalists must also take into account that these technologies also influence the biases that lead to dangerous discourse.

"All the information that these artificial intelligences are being trained on also includes the same biases that are now creating this hate discourse as well," Zamora said. "It’s very likely that hate speech and dangerous discourse can also even continue to be reproduced from the creation of content by these tools."

Juárez said that when facing the strong emotional charge of dangerous discourse, it would appear that journalism techniques lose strength. Journalists face a formidable challenge in finding ways to respond to these narratives that create disinformation and incite hatred. However, they can do it with the most traditional journalism techniques, such as contrasting, verifying and adopting different approaches.

"What we see happening when, for example, we cover an anti-racist agenda, migration, [or various] feminisms is that we find in social media or in the public debate responses that do not focus on these nuances and this dialogue, but [rather] stoke the fire, passions and the often anonymous stances that incite virtual or physical violence," she said.

Dangerous discourse sometimes seeks to stigmatize members of a certain social group, or to re-victimize people who have suffered a crime or violence.

Mendoza and Alvarado gave the example of the murder case of Debanhi Escobar in Nuevo León, Mexico. During the coverage of this crime, the 18-year-old girl was labeled as an "escort" by the media, most of which highlighted details of the victim's private life instead of exploring in depth the crisis of violence affecting women in Mexico.

"This discourse stigmatizes, not only the victim, because it makes her appear as the cause of her own misfortune and ills [...], but also stigmatizes sex work," Mendoza said. “This has to do with the revictimization of women and with brushing aside the issue of very serious gender violence happening in our country, by labeling it a spectacular case, an unprecedented case, something different outside the norm, when the norm in Mexico is that women are victims of femicide.”

The journalist added that migrants are another group that is commonly stigmatized in journalistic coverage and are portrayed as individuals seeking economic benefit in another country, whereas the phenomenon of migration also has to do with other causes, such as the economy, violence and climate change.

Zamora reminded the audience that what happens in social media is a reflection of what happens in society, and vice versa. That is why journalists must be aware that the way they tell stories has an impact on reality.

"If there are a lot of people in a society who are extremely racist or misogynistic, that translates immediately to social networks," he said. “The violence you see on social media, on the internet and in the media, the way we headline or write this or that piece of news, has real-world consequences.”

Given this scenario, journalists must be clear about their role of paying attention to plurality, a diversity of opinions and their contrast to avoid falling into a discourse that attacks groups or ideological positions, Juárez said.

"We have a great responsibility in our hands to stop these kinds of discourses that harm people and make them suffer, because they provoke death in its extreme degree," she said.

In Latin America, authoritarian governments that draw a black and white reality and create polarization in society are gaining strength. Journalists, Juárez said, must be self-critical to avoid adding to this polarization.

Giving voice to individuals with dangerous discourse can have effects on reality, Zamora said. (Photo: Screenshot from Folha de S. Paulo)

"These open dialogues [...] require us to sit down and make a deep exercise of self-criticism, first as journalists and then as societies, about who wins with these polarizing discourses," the journalist said. “When we talk about the life and physical integrity of people [...] it’s important to stop and think about the discourse of journalism, which has often been a warlike discourse, an inflamed discourse, a discourse that does not consider these nuances.”

Juárez, Mendoza and Zamora agreed that individuals who engage in dangerous discourse should not be given a voice in order to respect freedom of expression or journalism’s objectivity, when it comes to inciting violence or harming groups or individuals.

"We have gone beyond this dialogue about objectivity and subjectivity and focus instead on journalistic rigor and the quality of public dialogue we are promoting, without inciting violence, being very clear on these boundaries between freedom of expression [and dangerous discourse]."

Identifying dangerous discourse in time can prevent it from going viral and ending up fulfilling its goal of causing harm. Although journalism cannot prevent these harmful narratives from emerging, it can help to keep them from spreading.

"It’s necessary to take into account whether the message is hostile to a certain group of people, or to a specific person. And also take into account to whom it is directed. If this discourse is aimed at a vulnerable group, then surely we are facing a very dangerous discourse and we can avoid spreading it," Mendoza said.

Zamora said that a good strategy to neutralize these messages is to analyze them rationally. He also said that journalists should think twice before voicing their opinion or joining discussions on social media that could contain dangerous discourse, as this could contribute to them gaining strength.

"We have to take into account that while algorithms work by showing us only what we like, they also work by showing us what keeps us there the longest," he said. “In a social media discussion on any of these topics it can make you spend all day replying to tweets or comments. What that does is give a lot of relevance to a comment that maybe might have gone unnoticed.”

Polarizing and disinformation dialogues tend to numerically feed the number of interactions on social media, although not necessarily in terms of quality, Juárez said. That is why it is necessary to be aware that giving visibility to figures who generate dangerous discourse helps them with their ultimate goals.

"Who wins? Maybe all these algorithm generators who gain publicity and spaces while a dialogue within society loses," the journalist said. "We can think differently and the direction is respect and dialogue, but obviously these types of discourse are not geared for that. What they are geared for is to feed animosity. And it’s the political parties, it’s the companies who win, who find favor."

Sometimes reporters covering day-to-day political events in their countries are forced to cover statements by officials or candidates that could potentially be dangerous discourse. In view of this, Mendoza recommended including the necessary information and context so the audience understands that such statements could be violating someone else's rights.

"If we realize that we are going to give a voice to someone who is not worth giving a voice to, but we’re being asked by the newsroom to do so for the sake of article, we can take advantage of those moments to include something else in our texts, such as why what [the interviewee] said is wrong," she said. "Somehow with that we can mitigate a bit the flooding of this type of discourse, the media and networks when we can't avoid it."

Among the final tips to combat dangerous discourse while doing diversity coverage the panelists offered to the webinar audience, Juárez recommended that newsrooms develop a strategy in their codes of ethics and editorial lines to outline the approach to be taken in such coverage.

Juárez said that Periodistas de a Pie does journalism with a position on issues such as migration, feminism and the anti-racist agenda. (Photo: Screenshot from Periodistas de a Pie)

“At Periodistas de a Pie we do have a situated journalism [...]. We do have a position on issues such as migration, feminism and the anti-racist agenda, but it is very important to us for this dialogue with audiences to also involve listening to other points of view. This can concretely be set down in protocols, in style manuals, [and] in codes of ethics.”

For her part, Mendoza said that her Verificado team has two strategies to combat dangerous discourse through the narratives of their stories. One is the creation of an alternate narrative through informative products that can fill information gaps that are susceptible to becoming disinformation and subsequently hate speech.

"An alternate narrative is when we develop an in-depth approach to a topic by explaining that what usually circulates out there is stigma and what it truly is, where we give ourselves the opportunity to work on a specific issue in a broader way, with specialists, with data, with facts," she said. “This creates information that at the end of the day produces knowledge, which is what journalism is all about.”

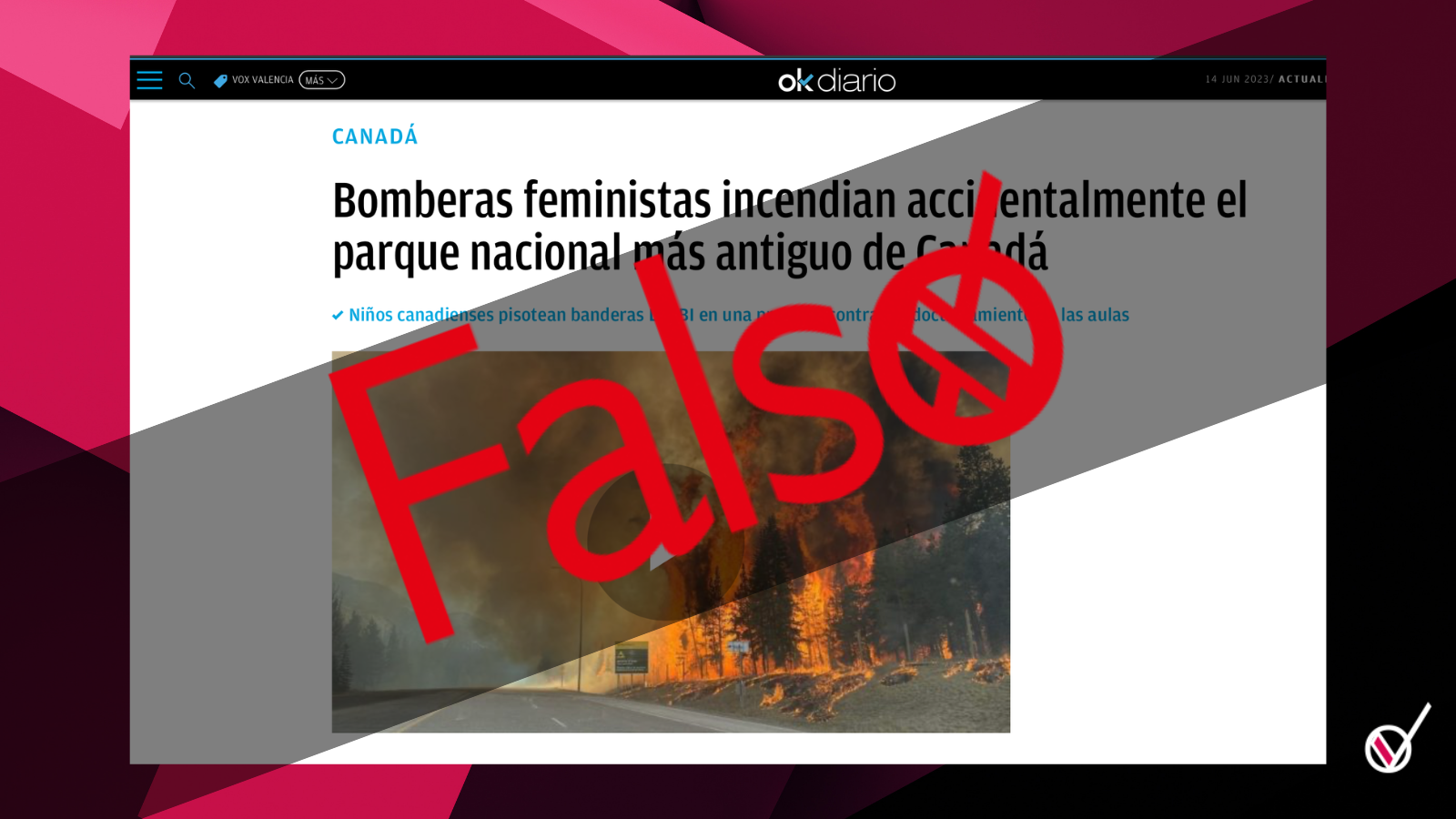

The second strategy is to promote a counter-narrative once dangerous discourses have already begun to generate disinformation. A counter-narrative, Mendoza said, is an immediate response to a fact that is already being created or that is reinforcing stigma or stereotypes.

"It’s precisely going out to combat an adverse narrative that is already circulating. So we have to create a counter-narrative, we have to point out, with words, with facts, with data, that what is circulating there is misleading or false and that it’s dangerous. Because, at the end of the day, it can create an environment of discrimination and of restriction of human rights for a specific group of people," she said.