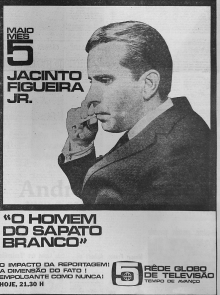

Prisoners accused of petty crimes taken straight from the scene of the crime to television studios to be subjected to inquisitorial interviews in front of the cameras. Non-Christian religious rites treated as frightening exoticisms. Surgical procedures turned into spectacle. Fights between actors pretending to be simple people brawling over trivial conflicts. All these have been presented as if it were journalism with direct access to the real thing, without the filter of modesty or hypocrisy. "The story’s impact! The fact’s extent!" said an advertisement from May 1968.

The incidents described above can evoke many TV shows around the world, but they refer specifically to innovations in Brazilian television introduced by Jacinto Figueira Júnior, better known by the nickname O Homem do Sapato Branco (The Man with the White Shoes). Beginning in the early 1960s and continuing, on-and-off, for almost four decades, he went on the air in the biggest Brazilian cities with a formula that mixed facts with hoaxes, denunciations with entertainment, pretentious moralism with a brash ambition for ratings. His work left a legion of imitators and offspring who still today occupy prime time slots in major Brazilian channels.

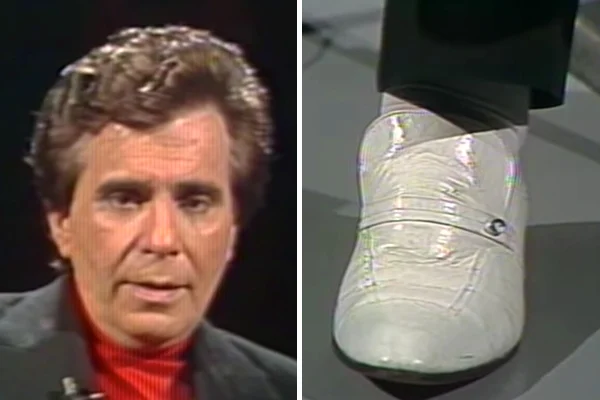

Jacinto Figueira Jr., also known as "The man with the white shoes" (Photo: Screenshot from Youtube/SBT)

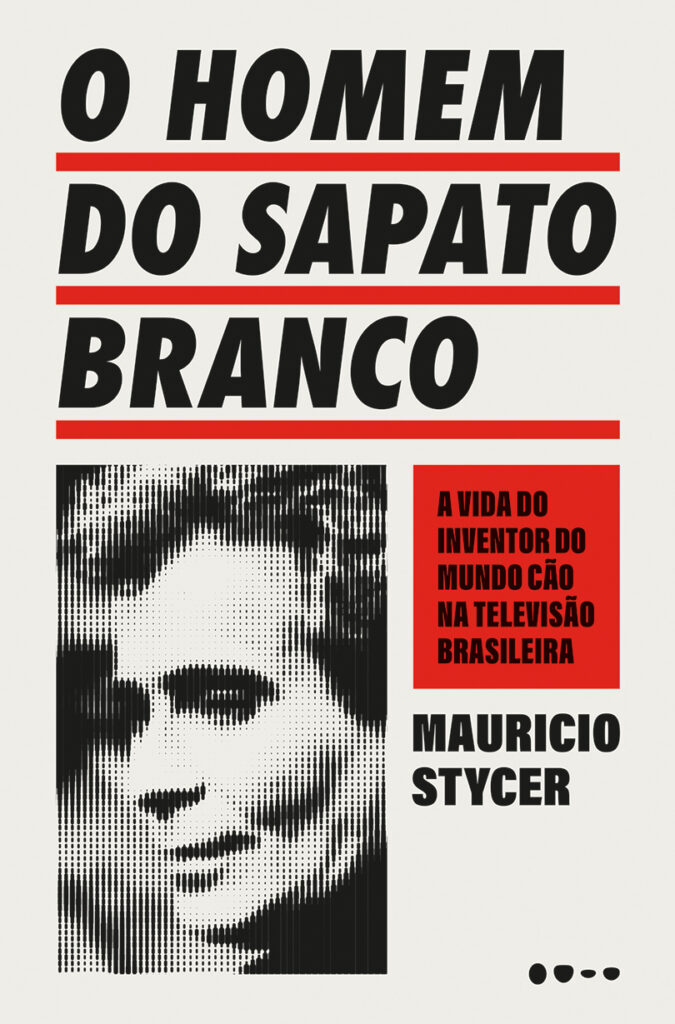

The professional trajectory, personal history and innovations in TV promoted by Figueira Jr. were little known until recently, but not anymore, with the release this month of "O homem do sapato branco: A vida do inventor do mundo cão na televisão brasileira [The Man with the White Shoes: The life of the inventor of the dog-eat-dog world on Brazilian TV]" (Editorial Todavia), by Maurício Stycer. In the book, the author, who writes columns for Folha de São Paulo and the UOL newsite, and is the most experienced TV critic active in the Brazilian media, contributes to the understanding of the emergence in Brazil of an over-the-top style of TV journalism, which has amazement and shock as its main production values.

"I’ve always been interested in sensationalism, and in the past I even dreamed of writing a book telling the history of sensationalism in Brazilian TV," Stycer told LatAm Journalism Review (LJR). "Often, while reading texts about the history of television, Jacinto's name would come up. But if you Googled it, what you found was enough to write a maximum of two pages. I thought, 'this guy is always mentioned as a forerunner, but there is no information about him. So I wanted to tell the story of who he really was.”

Figueira Jr., according to Stycer's research, inaugurated three tendencies that still persist today in Brazilian television. The first was that of police TV shows that glorify police actions, expose criminal suspects without worrying about their right to due process, and provoke a permanent sensation of alert and panic.

When Figueira Jr. started working as a producer for the São Paulo TV Cultura in 1961, Brazilian police TV journalism already existed. The TV host and journalist, however, transformed it into a much more intense and aggressive attraction.

Humble people would appear on the air handcuffed before even passing through a police station. According to the book, the program's production team had an agreement with an investigative police unit, which took the suspects.The interviews resembled interrogations where the word of the accused had little value. The convictions were given in advance. According to Figueira Jr.'s words, rescued by Stycer, "there was only one objective: To alert society, because society is responsible, we are all responsible."

This tradition is still very much alive in Brazilian TV today, especially in afternoon programs on regular broadcast channels, such as those presented by José Luiz Datena, Sikera Junior and Luiz Bacci. They no longer take prisoners into the studio, but still interview handcuffed people live.

Brazilian TV critic Mauricio Stycer, who authored the book. (Photo: Renato Parada)

"A very clear characteristic of these programs is to try to stoke fear, a feeling that stimulates the audience," Stycer told LJR. "They also don't always try to follow basic journalism rules, such as showing all sides, not making unfounded accusations, not forcing people to give interviews, nor sticking the microphone in the face of someone who has just been arrested."

The book analyzes how the police appear as a solution to all problems in these shows, which never bother to make an analytical effort or discuss the cause of social ills. "Instead of criticizing the lack of State investment in essential areas such as health, education, sanitation or employment, they call for a greater police presence," Stycer writes.

Another trend that Figueira Jr. started was that of stories in which reporters present themselves as champions of consumer protection, seeking to constrain those allegedly responsible for abusive practices by means of the on-camera.

Sometimes the reporters went after allegations so unsubstantiated that they created legal problems for themselves. In 1967, for example, accompanied by the police and his TV crew, the newscaster raided a psychiatric hospital but found no wrongdoing. In response, the clinic staff sued him. This kind of journalism still exists on Brazilian TV, in figures like the federal deputy Celso Russomano, who presents the "Patrulha do Consumidor" (Consumers’ Patrol) on TV Record.

Figueira Jr. 's third type of influence was that of talk shows to try to solve petty domestic conflicts, such as between relatives, neighbors or ex-lovers. Televised mediation often ended in fights. In these programs, which are reminiscent of what Geraldo Rivera did on American TV between 1987 and 1998 and are more openly distant from journalism, the irresponsible handling of information becomes more apparent.

An ad from May 1968 that says: "The story’s impact! The fact’s extent!" (Image: Courtesy)

Stycer gathers several testimonials in his book from people who say that, secretly, the program would hire actors to stage supposedly true litigious situations. This genre still exists in Brazilian TV, as for example in the João Kléber Show, and, according to the author, "it was born or at least developed a great deal in Jacinto's programs."

In response to ethical questions, Figueira Jr. always braced himself with the argument that he only showed reality in a raw way. An ad for one of his SBT programs in 1981 said "Jacinto Figueira Jr. presents the naked reality in a polemic, live, aggressive, factual show." In another ad disguised as a reportage from the same year, the host himself stated: "We’ve never been concerned with fancy production and miraculous special effect techniques. We’re interested in facts, and only facts. To focus on them within their full reality, to keep it raw and alive, is what we’ve always done.”

Stycer notes how this rhetoric worked as a marketing tool. "He needed to sell himself as a champion of truth. As a guy who is telling the truth, who is helping solve people's problems. Because if you watch his program knowing that it could be a sham, it takes on a different weight. You always have to reinforce that you are telling the truth," he told LJR.

Besides analyzing Figueira Jr 's career on TV, the book also tells his personal story. Son of middle-class Portuguese immigrants, he was born in São Paulo in 1927. In his youth, he dreamed of becoming a singer, and entered the world of media in 1960 selling advertising quotas for TV Cultura, then belonging to the group Diários Associados, also owner of TV Tupi, the country's largest broadcaster at the time. His nose for what was impactful, combined with the fact that he was on a precarious channel which had a penchant for experimentation, allowed him to move into journalism, first behind and then in front of the cameras.

The nickname "The man with the white shoes" came about in 1965, with the premiere of a TV show of the same name. Figueira Jr. several times attributed the epithet to quotes from philosophers Friedrich Nietzsche and Arthur Schopenhauer, but his producer Mário Fanucchi claims that it’s actually due to "the figure of the Brazilian malandro [bum], who loves white shoes.”

From the 1960s until the late 1990s, most major Brazilian television stations — including Globo, Bandeirantes, and SBT ― broadcast several shows and TV segments of the White Shoes Man. Few television records of his early days are still available, so for his research Stycer had to rely on interviews and journalistic accounts of the time.

Jacinto Figueira Jr. on his TV show on SBT in the 1980's (Photo: Screenshot from Youtube/SBT)

Besides his media career, Figueira Jr. took another path common to popular media figures: In 1966, he was elected state representative for the Democratic Brazilian Movement (MDB, in its Portuguese acronym) party. The choice for the party, which was the legal opposition during the military dictatorship in Brazil, was fortuitous, and happened after ties with former president Jânio Quadros (1961-1961). In March 1969, three months after the declaration of the Institutional Act 5 [AI-5], which hardened the regime in Brazil, Figueira Jr. had his term and political rights revoked for 10 years after a summary judgment.

"Although this was not stated in the documents I found about his disenfranchisement, my hypothesis is that the government feared he would become an even more popular and possibly dangerous figure. In the eyes of the military government, the fact that he attracted people’s interest might justify revoking his mandate. Because there is no evidence that he was subversive, leftist or corrupt," Stycer told LJR.

Figueira Jr.'s reporting style — which also included disturbing reports on drug use, the broadcasting of innovative medical surgeries, feature stories stigmatizing LGBTQ+ populations, biased stories against non-Christian religions, and topics such as incest — is summarized by Stycer with the term "dog-eat-dog world."

The expression became popular worldwide with the 1962 film "Mondo Cane [A Dog’s Life]," directed by the Italian filmmakers Paolo Cavara, Gualtiero Jacopetti and Franco Prosperi. A forerunner of the shockumentary genre, the feature film consisted of a collage of images with exotic and abject scenes.

Stycer has an explanation for why this aesthetic has such a great appeal. "It's because it's 'sensational' indeed. Sensational is what you're not used to seeing, like all these elements. As critics we regard them in a negative light, but for a lot of people it's attractive, interesting, [and] curious. For a lot of people, it's really showing reality. You can understand why it's successful, even politically," the critic told LJR.

Cover of the book "O homem do sapato branco: A vida do inventor do mundo cão na televisão brasileira [The man with the white shoes: The life of the inventor of the dog-eat-dog world on Brazilian TV]"

The end of Figueira Jr.’s life, who died in 2005, is melancholic. He had been away from the cameras since 1997, with the end of the program "Aqui Agora [Here now]" on SBT, where he presented a show called "Repórter do absurdo [Reporter of the absurd]," which produced stories with an openly fictional twist. Sick and with facing financial difficulties after having mismanaged his money, Figueira Jr. resented seeing on camera the success of people who followed his format.

While hospitalized, Figueira Jr. became, in what Stycer calls as an "atrocious irony," the subject of feature stories in afternoon programs as sensationalist as his own. In one of them, in 2001, he answered what, in his opinion, was the secret of his former success.

"There’s only one secret. You meet the people. You do what the people want. People watched because I gave what they wanted. People wanted me to show the evils of São Paulo, which nobody else showed," he said. "I’d say, for instance: 'My friend, do you know who your son is with right now? He is snorting cocaine or marijuana. But the father didn't know. I’d warn him. And people found that interesting.”