In the words of the spokeswoman for the Cuban collective Palanca, independent women journalists in Cuba are in a state of "important defenselessness" and under constant judicial and police siege.

To try to remedy this situation, for six months a group of 20 women journalists and activists have organized and created the Palanca collective. As a first endeavor, they seek to create "Casa Palanca"—a shelter for women journalists.

“The harassment against women journalists has been more brutal, more vicious, by the State, than against male journalists,” journalist and spokeswoman for Palanca, Marta María Ramírez, told LatAm Journalism Review (LJR). "There is a gender bias in political violence."

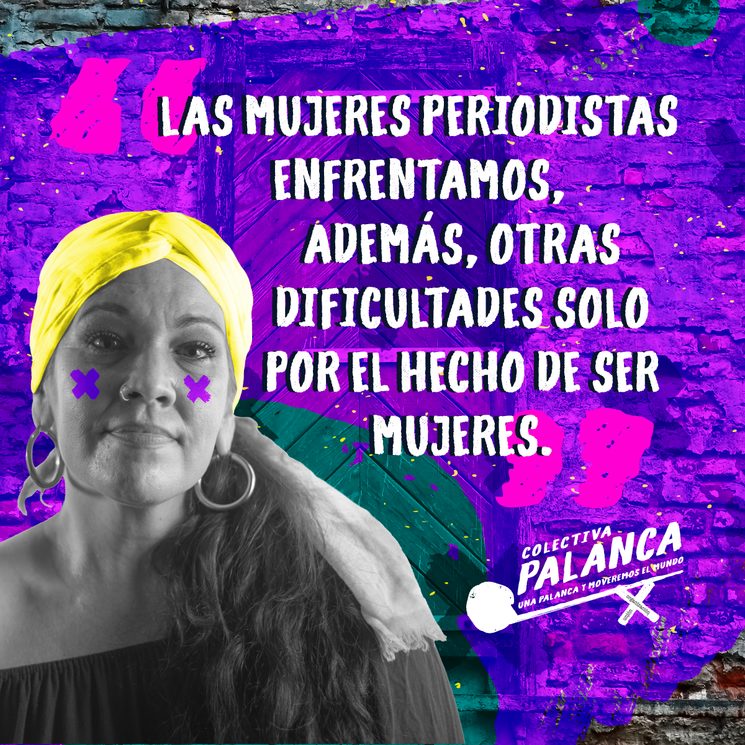

Image of the fundraising campaign for "Casa Palanca", by the Cuban collective Palanca. (Screenshot)

Through the Verkami fundraising platform, the group seeks to raise €25,000 (about US $28,000) to buy a property in Havana. The place would offer protection to women journalists, temporary lodging and child care, in addition to serving as a work space.

In particular, women journalists suffer humiliating arrests and interrogations by law enforcement, according to a special report on the situation of freedom of expression in Cuba, published at the end of October 2021 by the Office of the Special Rapporteur for Freedom of Expression of the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR).

One of the examples in the report is the case of journalist Iris Mariño from La Hora de Cuba, who in 2018 suffered 22 episodes of harassment against her. One of them was when State Security agents arrested her for trying to take a picture on the street.

Another case highlighted in the report is that of Adriana Zamora, a reporter for Diario de Cuba. According to the report, Zamora, who was pregnant at the time, was summoned to a police station and, during interrogation, one of the police officers allegedly threatened to make her miscarry.

Also, Cubanet correspondent Camila Acosta, who is currently under house arrest, was arrested several times during 2020 and has had to move more than 10 times because the police pressure tenants who rent her a place to live.

In addition to the arrests and interrogations, there are the judicial elements used by the Cuban regime to quash independent journalists, the Rapporteurship pointed out in its report. These are the processes for ‘seizure of functions and seizure of legal standing’ against those who practice journalism in non-official media.

"Not all women who are being harassed and who are in situations of sexist violence, whether within their families or by the State, denounce it publicly," the Palanca spokeswoman said.

According to Ramírez, in addition to all the difficulties journalists face for being independent and for being women in Cuba, they also lack sick leave, maternity leave, child care or any type of subsidy or retirement plan. This despite the fact that the majority pays taxes for carrying out other trades permitted by the regime.

With Casa Palanca the collective aims to lend a hand to their peers in trouble. "We are not going to solve, and we know it, all the difficulties we are facing at the moment, in a country with some important peculiarities, such as a significant housing deficit and with movement limitations between provinces."

What the group seeks with Casa Palanca is also to practice sisterhood, beyond ideologies, political beliefs, religions, geographical origins, life stories, social classes, according to Ramírez. “That is what we are envisioning and hopefully it will be replicated in other collectives and in other groups, not only in Cuba, but also within the region.”

Fundraising for Casa Palanca will be open until mid-February.