Pedro Valtierra Ruvalcaba is the fourth photographer to receive the "Fernando Benítez" National Tribute to Cultural Journalism at the Guadalajara International Book Fair (FIL) in Mexico, an award that has been given every year since 1992 to leading figures in journalism with a solid body of work and a long career.

The homage took place on Dec. 4, during the closing of the 2022 edition of the FIL. The recognition honors the 50 years that Valtierra has been practicing photography, since he received his first camera, a Kodak Instamatic, at the age of 16.

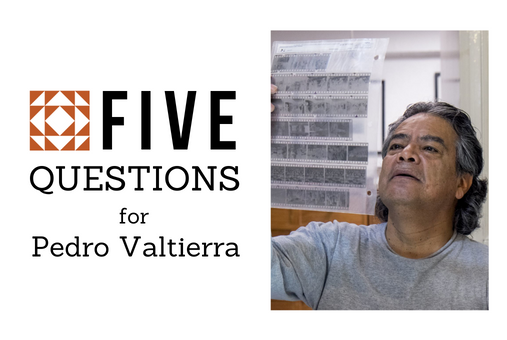

Photo: Isabel Mateos/Cuartoscuro. Banner: Edgar Chávez/Cuartoscuro

Since then, Valtierra has developed an outstanding career in photojournalism in iconic Mexican newspapers such as El Sol de México, Unomásuno and La Jornada. But he is also responsible for an important boost to the recording and preservation of documentary photography in Mexico, through the agency he founded in 1984, Cuartoscuro, as well as the magazine of the same name.

Valtierra, born in Fresnillo, in the state of Zacatecas, defines Cuartoscuro as an agency devoted to recording Mexico's important issues from an independent and open perspective. The magazine has published the work of more than 4,500 photographers, mostly Mexican.

A couple of weeks after the tribute, Valtierra spoke with LatAm Journalism Review (LJR) about the tribute, about how he uses social media to keep his photographic work alive and about how for him the threats and violence suffered by the press is nothing new. He has experienced them firsthand for decades, when he covered the Sandinista Revolution in Nicaragua or the Indigenous uprisings in Chiapas.

*This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

LJR: What does it mean for your career to have received the FIL's "Fernando Benítez" National Tribute to Cultural Journalism?

Pedro Valtierra: It’s a quite significant homage to my professional career, which dates back almost 50 years. It’s an important incentive, especially coming from the FIL, an important organization in Mexican culture, and bearing the name of Fernando Benítez [Mexican journalist who established several cultural supplements in prominent written media in Mexico] is something that makes me feel happy and grateful. This distinction is given to very few people and now that it is my turn, I am very happy, very grateful. As my friend [also a photographer] Julio Mayo used to say, you have to receive awards, be grateful for them and enjoy them. But don’t buy them either.

LJR: You have an Instagram account with more than 10 thousand followers. What advantages does it bring you as a photojournalist and what do you think of the fact that new technologies and social media are occupying the space that used to be covered by photography?

PV: It doesn't bring me many advantages. Not economically, no. But [with Instagram] you are paying attention, you are up to date, you are relevant. I am uploading my historical photos and that gives you relevance, it gives you a presence in the contemporary world. And well, as they say, you have to renew yourself, you have to keep up. I’m there, guided a bit by the people who work with me.

Mexico is a country in which the situation is quite adverse for journalists in general. And well, now with all this digital stuff, TikTok, social media in general, it has generated a disadvantageous situation for journalists, because it’s taking away a lot of jobs, a lot of work. But there’s nothing we can do because these are times of change. We can’t do much, we can only offer quality, offer better alternatives as photographers, better points of view, better work, with more rigor. In the world, digital is changing the media. The disadvantages it has now for professional journalistic photography are many, because now the media are largely supplied with photos from the social media, from people in the street. Now a phone is a camera. And then everything is depicted, everything is photographed everywhere. The truth is that this limits the development of photography a lot. I bet, I believe, I am confident that quality photography will prevail in the end. The media will have to work more with professional photography in the end.

LJR: In your career you covered conflicts in Central America, where today journalists are under siege and persecuted, especially judicially. What was it like for you to cover these conflicts of past decades?

PV: It was a different time, a different era. There were problems in Central America. For example, I appeared, along with many other journalists, on a blacklist that a paramilitary group put out. In Nicaragua there was a lot of hostility towards photographers and journalists of all media. [Those involved] did not want diffusion, they did not want promotion and well, we journalists always looked everywhere for information. It was interesting to interview the guerrillas, and that was inconvenient to the State, the Army, the governments. That put the work of journalists in a complex situation.

However, that’s what happens, it’s a risky profession. I’m not complaining. Of course, in the 70s and 80s it was a very different situation from what we are living now. Particularly in Mexico, where violence against journalists and photographers has been terrible.

[...]

I think the Mexican media should be more concerned about these issues [social conflict in the region]. Because, in the end, it is information that has a lot to do with what’s happening in Latin America and I think it is important to have a reporter and a photographer telling those stories from the ground.

LJR. Speaking of violence, one of the journalists murdered this year in Mexico was a photographer, Margarito Martínez, in Baja California. Similarly, in Haiti, Maxihen Lazarre, was also a photojournalist. Do you think this violence will stop photojournalists from covering complicated subjects?

PV: I think the idea [of the violence] is to intimidate the press, both by some local governments and by organized crime groups that intimidate so the press doesn't publish anything. It’s a way of trying to silence the press. For example, there are states in Mexico like Tamaulipas, like Guanajuato, where journalists have practically ceased to exist. They’re not on the streets because of the risk, because of the justified fear of being killed.

The purpose of all these murders against the press is to limit, to silence, to silence the press in the face of the facts. I’m among those who believe no one should risk their life for a photo or story. I know that what I am saying is a bit complex, but it’s worthwhile taking care of ourselves, because the situation is really ugly. The Margarito case, for example, was a direct action against the press to intimidate a photographer who was doing important coverage, police coverage that had to do with these groups.

[...]

We covered a lot of [the social conflict in] Chiapas, where there was terrible repression. We received threats even from the Army itself and we never complained or stopped covering. We are not reckless either, we do everything carefully. But well, we have to continue in the profession. I say to my fellow photographers who are in Michoacán or in other dangerous places: "Hey, we have to remain calm, we have to remain honest above all. We’ve been invited by organized crime groups to do some feature stories. We go in, but we always maintain an attitude of independence and I feel that many of them know that. We are neither with the government nor with the criminals. We do journalism. And we don't qualify, because if we qualify then doors close. I prefer to record these violent things, which must be recorded for the future and for daily information.

LJR: What do you think documentary photography in Mexico is lacking?

PV: In Mexico what is missing is to continue working with important social issues. Rural issues, urban issues. There are many issues that we’re not covering. Maybe we should dedicate more time to political issues, but it’s important to cover all social issues, world issues. That’s what we need, social issues that are important to people.

[...]

I am 67 years old. I’m getting on in years, but I still have that journalistic spirit and above all a spirit of freedom that we have earned for many years now.