After nearly five years marked by instability, the entry and exit of six presidents, attempted coups and social protests with fatal consequences, Peruvians will head to the polls for multiple elections nationwide in 2026.

Presidential and legislative elections happen in April, and municipal and regional elections in October. Additionally, this year the Peruvian Congress will return to a bicameral system, requiring the election of senators and representatives.

With nearly 40 political parties competing, the team at El Comercio, the country's oldest newspaper, faces a colossal challenge: helping its audience digest the enormous amount of electoral information so they can make informed voting decisions.

To meet this challenge, the newspaper relied on artificial intelligence (AI) in conjunction with a technology that was previously unknown in its newsroom: automated workflows. This combination allowed it to develop two interactive data specials focused on presenting, comparing and scrutinizing candidates and their proposals, based on public documents. This was achieved without extensive programming expertise.

One of the projects presents a statistical-descriptive analysis of the candidates' life, career and assets. (Photo: Screenshot from El Comercio)

“These two election specials transform complex information into accessible and, above all, relevant knowledge during a crucial election period,” Gisella Salmón, head of audience retention at El Comercio and one of the authors of the pieces, told LatAm Journalism Review (LJR). “[The challenge was] navigating a sea of information overload, a huge amount of data that is also complex to understand quickly, but which, when analyzed holistically, yields quite interesting results.”

Automated workflows are sequences of digital tasks in specialized software that run automatically according to predefined rules. They allow different applications and platforms to exchange information, process data or perform coordinated actions.

The first encounter that the El Comercio team had with this technology was at the LATAM Newsroom AI Catalyst, an accelerator from the World Association of News Publishers (WAN-IFRA) in partnership with OpenAI, in which Salmón and Mayte Ciriaco, leader of the newspaper's innovative journalism lab, participated. The program is run by Fathm, a London-based media lab.

In the program, teams from 16 media outlets in the region learned about the strategic implementation of AI and developed prototypes to automate tasks, improve efficiency and transform editorial production.

Following their participation in the program, Salmón and Ciriaco devised the special features “36 presidential candidates, one vote” and “What does your candidate propose?”, which were published in December 2025 and January 2026, respectively. The first analyzes the presidential candidates' profiles, while the second examines their plans for the government.

“36 presidential candidates, one vote” is based on documents each candidate submitted to the National Elections Board of Peru (JNE), in which they give personal data, educational background, their professional profile, income, properties and criminal records, among other details.

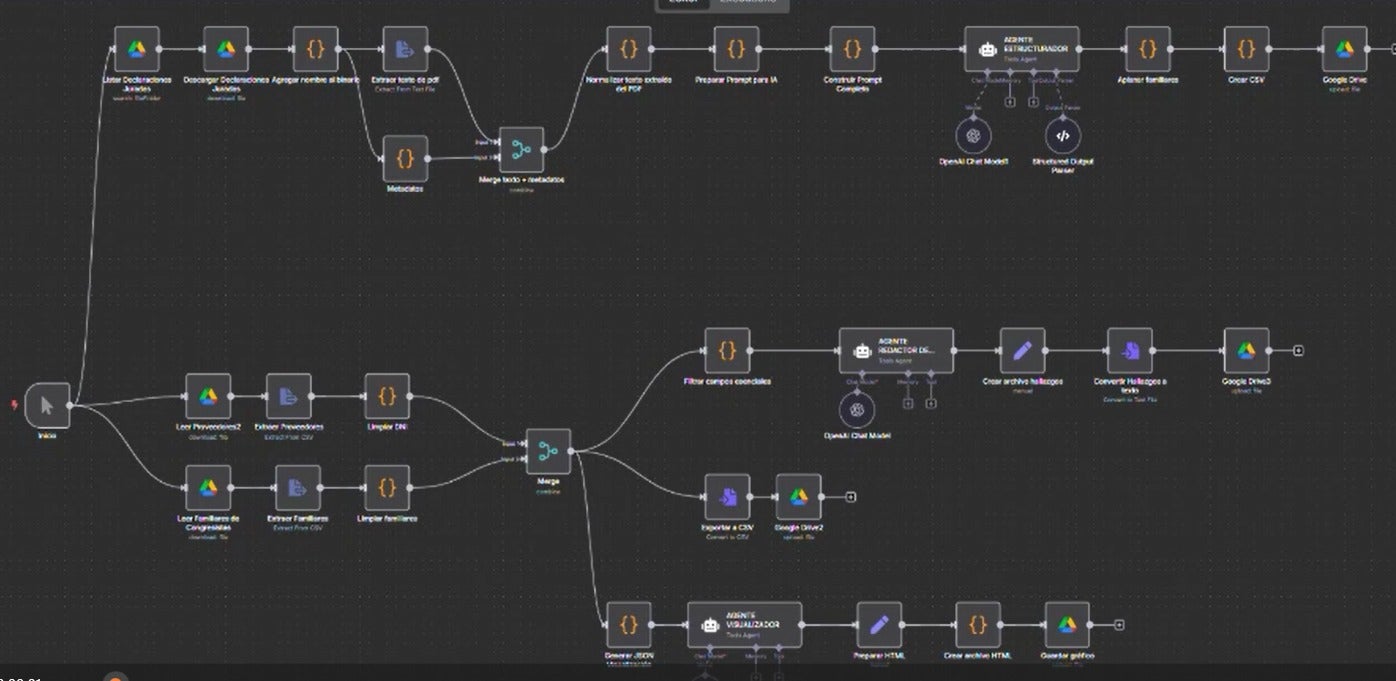

Using an automated workflow, the El Comercio team was able to extract, clean and structure the information from this profile information. This same workflow incorporated AI agents from OpenAI to analyze the data. The entire process was carried out on n8n, a platform that allows for the visual and intuitive execution of automated workflows without the need for complex programming.

The result was a statistical-descriptive analysis of the candidates' life, career and assets.

“The JNE [archive] is dense, very large and accessing it is complicated. And the path to find a candidate's profile information is very difficult. This made it hard for the average reader to quickly access and consult information,” Salmón told LJR. “The special profile section allows you to learn about the candidates in a visual way, from specific angles, such as where they were born, where they studied, how many are women, how many are men, their average age, and so on.”

Furthermore, the analysis revealed which candidates were vying for more than one position, who had the highest incomes, and their average level of education. In addition, using the extracted information, the special report presents summaries of each candidate with their profile data, presented in a more concise, practical and visually appealing format.

Similarly, “What does your candidate propose?” addresses each presidential candidates’ plans for the government and makes a feasibility analysis – how likely promises are to be fulfilled – of their proposals presented graphically, so that the user can objectively explore, filter and compare what the candidates propose and what they omit.

This second special report is also based on public documents from the JNE, which were cleaned and structured using automated workflows. The team then divided the government plans into units to facilitate analysis and, using AI agents integrated into the automated workflow, classified them by topic.

“What we’re aiming for, to make it more appealing to the audience, is not just to show a summary, but to allow them to compare proposals by thematic area,” Salmón said. “If you want to know what the candidates say about security, for example, you can select the topic, choose three parties, and then we’ll give you an overview of their security proposals so you know what each of them has to offer.”

The journalist emphasized that all the results generated by the automated workflows of both special reports were reviewed and validated by human observers. The feasibility analysis of the proposals for the second special report was also conducted by a human, Salmón added. For this, they had the support of El Comercio's political editor.

Automated workflows are made up of nodes, which are blocks of individual actions. (Photo: Courtesy)

“Initially, technology was involved in helping us find verifiable phrases [in the candidates’ proposals],” Salmón said. “But then we compared those arguments with specific quotes in legislation or current regulations, which were then reviewed again to ensure consistency. That’s the part where there was the most human intervention.”

Salmón said that the workflow methodology developed for these specials, which took more than six months to complete, is replicable and scalable so that, once the current situation has passed, it can be applied to other, even larger, specials.

“These are modifiable and adaptable architectures that can be used for other projects,” Salmón said. “We also hope that this tool can be validated again in October, when we have the municipal and regional elections, because we already have the workflows built.”

Automated workflows are made up of nodes, which are blocks of individual actions, which are connected to perform tasks without much human intervention.

Each node is linked to a software program or application, depending on the required action. Thus, there can be nodes connected to, for example, Google Drive or Microsoft Excel. Nodes can also be linked to code repositories to perform specific actions, or to AI applications. These latter applications function as "AI agents" when they are able to autonomously execute tasks based on natural language prompts.

Thus, the flows in n8n for the El Comercio specials included nodes linked to Google Drive to extract public PDFs, others with code for actions such as extracting and cleaning data, others linked to Google Spreadsheets to export the results to spreadsheets, and others linked to AI agents from OpenAI, for tasks such as analyzing information or writing texts, among others.

“If we have a folder with 50 PDFs containing sworn statements from members of Congress, and we want to transfer them to Excel, but we want the data separated into tabs, that's called structured data, which then allows us to program and analyze it,” Armando Scargglioni, a developer at El Comercio, told LJR. “That's something a human could do, but it would take many hours to open each PDF, read it, search for text, copy it and paste it into the corresponding tabs in Excel.”

This entire process can be automated in n8n, using a workflow with nodes for each action, which, in this example, results in an Excel spreadsheet with structured data. These automated processes reduced the workload for the El Comercio team by 80 percent, said Scargglioni, who participated in the technical aspects of producing the election specials.

Salmón said that automated workflows don't always achieve the desired results on the first try. However, one of the advantages of the node architecture is that if something goes wrong in the process, you only need to adjust the node where the error is occurring without affecting the others, and then run the workflow again, she added.

Automated workflows in n8n are considered "low code" because they don't require writing code from scratch. However, Scargglioni said that sometimes it's necessary to add code to some nodes to perform specific tasks.

However, someone without programming knowledge can request that code from generative AI platforms like ChatGPT, Gemini or Claude, Scargglioni said. In fact, he added, these platforms can be asked for a complete workflow.

“You don’t need to be a programming expert to create flows in n8n. [...] The [generative AI] models are so advanced that they give you the flows exactly as they are. They build them for you, and you simply download them and open them in n8n,” Scargglioni said. “N8n is a very powerful tool that I feel would be a great ally for writers if they could overcome their initial apprehension about it.”

The election reports made it clear to the El Comercio team that processing official documents with AI technology invariably involves the possibility of errors. And on several occasions, these errors are imperceptible to the naked eye. And if they go undetected, there is a risk of publishing erroneous or distorted information, said Lorena Obregón, an investigative journalist who was in charge of verification and quality control for the projects.

El Comercio's New Narratives team members Angela Peña, Armando Scargglioni, Gisella Salmón, Marcelo Hidalgo and Lorena Obregón. (Foto: Hugo Pérez / Diario El Comercio)

That's why human verification and journalistic judgment were fundamental at all stages of the development of the specials, Obregón said.

“AI does accelerate processes, but journalistic judgment remains fundamental,” Obregón told LJR. “And even more so when you use AI in elections; editorial judgment is the only thing that will separate this approach of responsible automation and misinformation.”

The AI agents used in the automated workflows for special reports made mistakes by confusing numbers or letters when extracting data or filling empty spaces in the documents with random information.

“That definitely has a huge impact because if that information wasn't verified, we could very well receive a cease and desist letter or a lawsuit. Or even [be giving] information that doesn't exist to the public,” Obregón said. “So it's not like you can blindly trust AI.”

Obregón said that the special section on government proposals alone consists of at least 400 texts that were read, verified, and, in some cases, manually improved.

“We’re a small team. Three of us worked on validating information, so each of us had to read more than 100 fragments to see if they were correct,” Obregón said. “And every time we made a change [to the workflow], we had to go back and revise it, or we made changes manually, because in some texts we felt that human writing was much easier to understand in some way.”

Furthermore, for the use of automated workflows, it is important to know how to create good prompts to give correct instructions to AI agents and to correct errors, Scargglioni said.

“When you see the agent making certain mistakes, you start identifying those errors yourself and improving the prompt,” Scargglioni said. “You had to create very, very specific prompts to prevent them from continuing to make those mistakes. Obviously, specifying things like, ‘Don’t imagine things, don’t invent information, if you find an empty field in the PDF, leave it as is, don’t fill it with data that doesn’t exist,’ and so on.”

Obregón said that the team noted each of the errors that the AI generated during the production of the election specials in order to advise the agents not to make those same mistakes in future projects.

Although El Comercio has a ten-point code on the ethical use of AI in the newsroom, the production of these two special reports reinforced in its creators the idea that technology cannot operate without human editorial judgement, Obregón said.

“Our team has more precisely defined which tasks can be automated, but there’s also a line separating this from which tasks must remain human responsibility,” Obregón said. “The lesson learned was that AI is useful for scaling, organizing and structuring public information. But it only works responsibly when there are explicit editorial criteria and people overseeing the entire process.”

Salmón agreed and said that after producing these election specials it became clearer to her that AI is not meant to replace journalists, but to enhance their work.

“When you create a prompt and are amazed by what can be achieved, that achievement isn't solely the AI's. It's the achievement of the person who knew what to ask the AI to do,” Salmón said. “And when you start working hand in hand with AI and understand the boost it can give you when used effectively, you learn that AI won't replace you because it doesn't have its own judgement. You provide that judgement.”

#Elecciones20265 ¿Qué propone tu candidato?

Una guía rápida para comparar planes de gobierno 2026–2031.https://t.co/S2u0FYukUh— Política El Comercio (@Politica_ECpe) January 22, 2026

This article was translated with AI assistance and reviewed by Teresa Mioli