The Amazon is the epicenter of climate change and therefore must be covered by journalists with a lot of preparation, including local voices, from approaches beyond the environmental, such as human rights, economics and politics, and with caution not to fall into the trap of misinformation.

These were some of the main lessons learned from the First Amazon Summit on Journalism and Climate Change 2022, held from June 9 to 11 in the city of El Puyo, in the heart of the Ecuadorian Amazon, according to some of its participants.

The Summit, organized by the regional non-profit organization Fundamedios, the Amazon State University and the National Federation of Journalists of Ecuador, brought together both Ecuadorian and foreign journalists, as well as activists and scientists. The goal was to open spaces for dialogue on the best ways to communicate climate change and conflict in the Amazon.

Helena Gualinga, environmentalist and activist, spoke about the importance of documenting and communicating globally what is happening in the Amazon from a human rights perspective (Photo: Screenshot of a YouTube livestream).

"The first thing to understand is that the environment, climate change and the Amazon, understood as part of the environmental issue, are issues of interest in general and should be addressed from different perspectives and not necessarily by environmental journalists," Antonio Paz, editor of the environmental media Mongabay, from Colombia, and a panelist at the Summit, told LatAm Journalism Review (LJR).

Paz, who moderated the panel "How should we tell the story of Climate Change?," said that journalists should be aware that the issues of the environmental crisis are relatively recent and both the media and people see them as very specialized subjects, far from their [everyday] reality. Therefore, journalists wishing to cover the Amazon must prepare themselves very well before embarking on their investigations, seeking both the right sources and the right language.

"We need to try to bring the issue to a more general language, so that anyone can understand it. And also understanding that what happens in the Amazon is not something that only matters to those [who live] in the Amazon. Rather, everything is related to everything else and, sooner or later, the fact of neglecting the important issues of the Amazon, such as conservation, protection of forests and water, etc., will end up impacting us all globally," he said.

Documenting and communicating globally what is happening in the Amazon from a human rights perspective and with the inclusion of local voices is important, said Helena Gualinga, environmentalist and human rights activist from the Amazonian territory of Sarayacu, who was the keynote speaker at the inaugural conference.

Gualinga, 20 years old, has taken her defense of the Amazon to international conferences on climate change. She spoke about how her uncle, Indigenous filmmaker Heriberto Gualinga, used his documentary "I am a Defender of the Jungle" to obtain justice for his community before an international court.

In 2012, the Kichwa Indigenous people of Sarayacu won a case against the Ecuadorian State before the Inter-American Court of Human Rights (IACtHR), after an Argentine oil company was authorized to enter the territory for exploitation purposes despite people being opposed to it.

"The Amazon depends on Indigenous peoples, Indigenous peoples depend on the Amazon; climate change depends on the Amazon," Gualinga said during his speech. "Yes, there is international coverage, but local media does not reach it as it should. Because here we have real knowledge of territory, we have access to the communities that are living through what is happening in the Amazon. Even we ourselves can communicate what is happening, we just need the space and openness to do so."

Regional or local journalists are more familiar with the context and problems of the Amazon, so when journalists from countries far from the Amazon rainforest or from non-specialized media are interested in covering this region of the world, partnerships and collaborative journalism become especially important, according to Paz.

"If there is interest from other countries that value what happens in the Amazon and understand all this objectively and with a much broader and not simplistic vision of an isolated territory, it is best to contact other colleagues who are working on the issue. They can provide context and help to understand what happens there, so this has a greater reach, a wider dissemination and so the right messages are transmitted," the Colombian journalist said.

Covering the Amazon from abroad should also involve avoiding the extractivism of information committed by some journalists who want to extract information and stories from a Western perspective, with prejudices and without respecting the beliefs and customs of the Amazonian communities, according to Alexis Serrano, editor of Ecuador Chequea and moderator of the panel "The challenges of Amazonian journalism: Ancestral knowledge, extractivism and the environment."

"Sometimes we look at all these issues from the bubble of the capital, of the city, of thinking that everyone has Twitter, that everyone has Instagram and, in reality, they don't," Serrano told LJR. "That was my main take-away [from the Summit]: Not to pretend that doing journalism is the same everywhere; in my case, doing journalism in Quito [Ecuador].”

The editor pointed out that Indigenous communities have little access to Internet and electronic media, so the medium with the greatest reach in these territories is radio. There are outstanding examples of community radio stations in the Amazon territories that fulfill the mission of keeping their inhabitants informed. Although most are small radio stations formed by the inhabitants themselves, that cover little beyond their communities.

"Since these are communities that have a lot of orality, radio is very important to them. That is why community radio stations fight so hard for the radio spectrum, so that their community radio stations can reach further," he said.

Stripping away prejudices when covering the Amazon also means making room for the knowledge and values of the Amazon’s Indigenous people in journalistic stories, according to Isadora Romero, Ecuadorian photographer and audiovisual producer. She is the winner of the World Press Photo 2022 contest in the Open Format category, in both the global and regional categories.

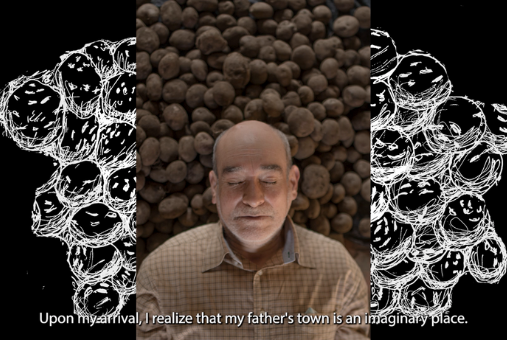

Romero was a special guest at one of the Summit's panels, where she presented the project with which she won the competition: "Blood is a Seed." It is an audiovisual piece on the loss of cultural memory in relation to the protection of seed diversity, forced migration, racism, colonization, and the loss of ancestral knowledge of the Indigenous community of Camuendo Chico, in Ecuador.

"Blood is a Seed" is an audiovisual piece by Ecuadorian documentary filmmaker Isadora Romero, winner of the World Press Photo 2022 Open Format competition (Photo: Screenshot).

To cover the Amazon in a fairer way from the point of view of photojournalism, photographers and documentary filmmakers should seek to tell those stories that have to do with other types of knowledge beyond Western science and hegemonic views, Romero said during her presentation. She added that the fact that these belief systems are often not quantifiable and tangible knowledge does not mean that they should not be part of the stories.

"There are still a lot of media that think that taking a photographer to cover a story is simply to illustrate the text. I think that is a total waste of what could be a new way of seeing, a new area that could broaden the discourse, that could include other perspectives," she said.

In her opinion, photojournalists should begin by exploring beyond photography to tell a story with greater accuracy about the reality of Amazonian Indigenous communities.

"These new formats that World Press Photo decides to award allow us to talk about all these things that sometimes we can't connect to only from words or a still image," she said. "We have this whole communicational spectrum that allows us to connect with people on other levels."

Climate change is a topic particularly susceptible to misinformation. Denialists and other movements that reject documented realities have increasingly sophisticated ways of disseminating false or misleading information. And journalists covering the Amazon have to be extremely vigilant.

Alexis Serrano addressed this issue in the workshop "How to combat disinformation and fake news," which he taught as part of the Summit.

The origin of the disinformation about the Amazon is not limited to those who share false information. It also has to do with the fact that this area of the world is not being covered as it should.

"From the first Summit panel, the main complaint was that the Amazon region has not been covered enough," Serrano told LJR. "The Amazon population has been neglected information-wise and efforts must be made to cover it more and better."

Journalism’s fast pace can cause journalists to inadvertently fall into misinformation when working on the issue of climate change. That is why it is necessary to get immersed in the subject.

"The first thing is to be very well informed, to read, learn, ask questions, and consult expert sources. And I would even recommend, if the subject is highly complex, to prepare before a formal interview by trying to figure out basic, structural questions about concepts," Antonio Paz told LJR.

Consulting a variety of sources and specialized sources will also reduce the risks of falling into the trap of misinformation. In environmental and scientific topics, one should go for specificity when choosing sources, the journalist said.

"A biologist can talk to you in general about how an animal species is doing. But if you want to know specifically about its interactions with the environment, you should look for an ethologist. If you are going to talk about viruses, look for a virologist and not someone who works with parasites or bacteria," Paz said. "It's about looking for the right sources and not stopping at the more general sources."

During its two days and throughout its 10 keynotes and panel discussions, the 1st Amazon Summit on Journalism and Climate Change brought together nearly 700 attendees, including journalists, scientists, activists, academics, students, and citizens, on the campus of the Universidad Estatal Amazónica, in El Puyo, the capital of the province of Pastaza, in Ecuador.

Panelists also included Milagros Salazar of Convoca (Peru); Mónica Valdez of the World Association of Community Radio Broadcasters; Maritza Félix of Conecta-Arizona (United States); Gesell Tobías of La Voz de América (United States); Cristian Ascencio of Connectas (Colombia); Susana Morán of Plan V (Ecuador); Isabela Ponce of GK (Ecuador); and Diego Cazar of La Barra Espaciadora (Ecuador).

The Summit's Tech Camp was attended by 70 journalists who worked for eight hours in workshops focused on new journalistic tools (Photo: Fundamedios Instagram).

"There is no first without a second. I can already tell you that we have made a firm decision to hold the second Amazon Summit on Journalism and Climate Change," César Ricaurte, executive director of Fundamedios, said in the closing speech of the event. "This first summit has been an extraordinary experience [...]. Having this exchange with the scientific community, as human beings, as journalism professionals enriches us greatly. [...]. Listening to community journalists, learning from them and understanding their needs is also an extremely valuable learning experience."

he Summit, which also had the support of the European Union in Ecuador, the U.S. Embassy in Ecuador and the UNESCO Regional Office for Venezuela, Colombia, Ecuador and Bolivia, also offered four workshops and a Tech Camp. Seven journalists from Ecuador and Peru, mainly from the Amazon region, participated in the latter. For eight hours, participants worked in various workshops focused on new journalistic tools.

"The location of the Summit, in El Puyo, in the heart of the Ecuadorian Amazon, allowed us to learn first-hand about the effects of climate change and the consequences of legal and illegal extractive practices. We learned it from the voice of the main people affected, who are the inhabitants and the Indigenous communities," Kevin Arteaga, a Venezuelan journalist from the newspaper El Carabobeño, who participated in the Summit, told LJR. "It is imperative to show the social face of climate change through the stories of those affected. As well as to emphasize the reporting of what it means for countries adapting to climate change in economic terms".