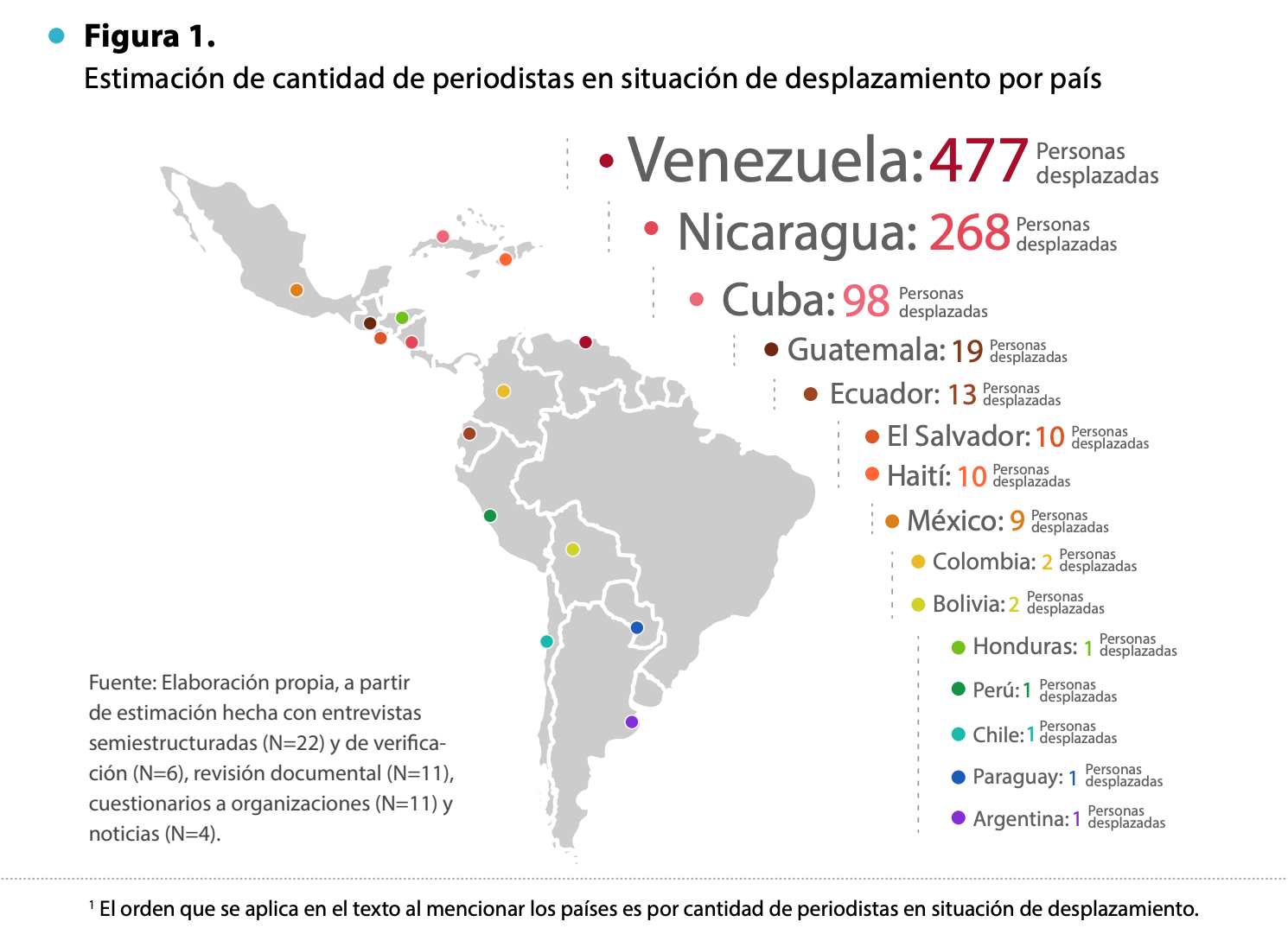

From 2018 to 2024, nearly 913 journalists from 15 Latin American countries have been forced to move to other countries to protect their lives, their safety, and that of their families. A large portion end up leaving the profession altogether.

This estimate comes from the recently released report "Displaced Voices: A Snapshot of Latin American Journalistic Exile 2018-2024,” whose authors say the figure represents an open wound in Latin American democracies.

The figures on journalist displacement in Latin America represent an open wound in the region’s democracies, the report found. (Photo: Screenshot)

“The fact that 15 countries have expelled journalists simply for doing their jobs reveals that democracies in Latin America are undergoing a significant process of erosion,” Óscar Mario Jiménez, a researcher at the University of Costa Rica and research coordinator of the report, told LatAm Journalism Review (LJR).

“Displaced Voices” was developed by the Freedom of Expression Right to Information Program at the University of Costa Rica, press freedom organization Fundamedios and the UNESCO Chair in Communication and Citizen Participation at Diego Portales University in Chile, with support from UNESCO.

It found that Venezuela, Nicaragua, and Cuba are the countries from which the most journalists flee, accounting for 92 percent of displacement in the region. Meanwhile, Argentina, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, the United States, Spain and Mexico are the countries that receive the most displaced journalists.

Furthermore, the report finds the two main reasons for the international displacement of journalists are political persecution and threats from organized crime or corrupt actors.

“We noticed that [the forced displacement of journalists] was a growing phenomenon and that it had affected several countries, but a regional perspective was needed,” Jiménez said. “This is like a first attempt to take a more global look at the phenomenon in Latin America.”

The figure of 913 displaced journalists is an estimate obtained from a methodology that included interviews with organizations, online surveys, and focus groups with journalists in exile. However, Jiménez said the real number is likely higher.

“We are absolutely certain that there are more than 913 [displaced] journalists,” he said. “Many journalists do not report [their departure] to any organization, and the States do not keep an inventory of those who leave or those who enter.”

The report ranked Latin American countries according to the number of journalists expelled. Leading the pack with the highest numbers of forced departures are Venezuela, Nicaragua and Cuba. They are followed by Guatemala, Ecuador, El Salvador, Haiti and Mexico. Then come Colombia, Bolivia, Honduras, Peru, Chile, Paraguay and Argentina. Finally, Belize, Costa Rica, Panama, the Dominican Republic, Puerto Rico, Uruguay and Brazil are countries where no forced departures of journalists were recorded.

However, since the investigation was completed, the situation of journalist displacement has worsened due to various factors, Jiménez said. These include the U.S.’s elimination of "humanitarian parole" to Venezuelans, Cubans, Nicaraguans and Haitians, and the consolidation of President Nayib Bukele's authoritarian shift in El Salvador, where constitutional changes have accelerated the suffocation of journalism.

“El Salvador, which in December 2024 was estimated to be a country with moderate emigration, has moved up one notch in our categorization, because in the last three months alone, the Association of Journalists of El Salvador (APES) has indicated that approximately 40 or 50 communicators have left that country,” Jiménez said.

The report identified the main consequence of the forced displacement of journalists to be the diminishing of citizens' access to accurate and timely information within their own countries. The majority of a group of 98 journalists in exile who responded to a survey for the investigation mentioned that leaving their country meant the creation of a news vacuum, Jiménez said.

"News deserts are forming where some topics aren't discussed, some issues aren't addressed, some problems aren't highlighted, which ultimately ends up affecting democracy itself," he said.

With just US $100, a small backpack full of clothes, and knowing no one, journalist Víctor Manuel Pérez arrived in Costa Rica in August 2018, fleeing his native Nicaragua. His mother had begged him to leave the country in the face of a crackdown on the press by Daniel Ortega’s dictatorship during the so-called "cleanup" operation, a wave of repression against social protests that erupted that year.

Upon arriving in Costa Rica, Pérez faced most of the main challenges for practicing journalism exile that were documented in “Displaced Voices”: achieving legal standing; confronting rejection and xenophobia; maintaining security of sources on the ground; ensuring personal and family safety; and overcoming legal and professional obstacles to practicing.

Displaced journalists from Venezuela, Nicaragua, and Cuba represent more than 92% of the total of Latin American journalists in exile, according to the report. (Photo: Report "Voces desplazadas: radiografía del exilio periodístico latinoamericano")

After hopping from one accommodation to another until settling into a shared room with eight other people, Pérez had trouble formalizing his refugee status. He had to wait in line every day for a week just to make an appointment to submit his application.

“I would leave from 3 a.m. until 10 a.m., when they closed, and I had to go for at least a week straight because there was never any space,” Pérez told LJR. “In September [2018], I applied for refuge. They gave me an eligibility appointment in 2026, which is the interview to determine whether or not you'll be granted refuge.”

Thanks to his investigative skills, Pérez researched the case and filed an appeal for protection. Five years later, in 2023, he obtained refugee status. However, during those five years of waiting, he was restricted from performing almost any activity, from leaving the country to opening a bank account and, of course, working.

However, as soon as he could, Pérez resumed his journalistic work. With four colleagues he met in exile, he created the digital media outlet República 18. Together, they reported on the crisis in Nicaragua. Later, during the pandemic, he founded Intertextual, a digital project on LGBT+ issues, which he continues to work on to this day.

In line with findings from the “Displaced Voices” report, Pérez said the safety of his colleagues and sources in Nicaragua has been one of his main challenges. This has led his outlet to expand its coverage to other Central American countries.

“Sources [in Nicaragua] are no longer giving such public interviews. Very few sources still dare to speak publicly or give their names,” Pérez said. “For editorial reasons, for people who are still in Nicaragua, even if they tell us their names, we use pseudonyms or anonymity to avoid exposing them.”

Transnational persecution and persecution of families in one's homeland, another challenge identified in the report, was one of the challenges faced by a journalist in exile who asked to be identified as Ángela. Originally from a Latin American country with an authoritarian regime, Ángela left her country in 2018 due to the stigmatization and imprisonment that colleagues were facing back home.

With great effort, she was able to continue working in her profession within a few months, first in the communications department of a foundation and then in some feminist media outlets. But she soon realized that the persecution against her continued through harassment of her family in her home country.

Víctor Manuel Pérez is example of journalists who manage to launch their own journalistic projects in exile: he co-founded digital outlets República 18 and Intertextual. (Photo: Screenshot of Intersexual YouTube channel)

“Our fear, and many exiled journalists can tell you this, is that even though we're outside, there's repression against our families inside,” Ángela told LJR. “At first, I wasn't afraid. I reported, I identified myself, I showed my face and everything, but I stopped doing that because the harassment is very hard on the family.”

For both Ángela and Pérez, another of the toughest challenges has been achieving financial sustainability. Both agree that the cost of living in their host countries is considerably higher than in their places of origin, so they have had to pursue activities alongside journalism.

“Costa Rica is twice—and I dare say sometimes three times—as expensive as Nicaragua. And with the salary we had in Nicaragua, we can't live here in Costa Rica,” Pérez said. “I have to do other things to survive.”

In his spare time, the journalist drives for Uber and takes photos and videos at social events. Likewise, Angela said she's had to take on jobs such as cleaning beauty salons and bagging bread.

Since living in exile, every time sports journalist Diobert Tocuyo watches a soccer or basketball game, he is overcome with nostalgia at the thought of covering it instead of just being a spectator.

Since arriving in Chile in 2018 after fleeing the precarious conditions of his native Venezuela, he has been unable to return to journalism, despite now having legal residency in his destination country.

The low salaries in journalism in Chile and the loss of his Venezuelan professional degree forced Tocuyo to abandon his search for employment in his field and accept an administrative position at a podiatry center. His wife, also a journalist, has also been unable to find work in the media and works at a camping supply store.

“As a journalist, I haven't been able to find work. On the one hand, it's become difficult, and on the other, the salaries aren't very attractive,” Tocuyo told LJR. “I've stayed out of journalism, given that the jobs I've had the opportunity to be interviewed for are much lower than what I earn.”

Like Tocuyo, many displaced journalists end up abandoning the profession due to factors such as difficulties in formalizing their immigration status, the impossibility of validating their job accreditations, and the complexities of launching their own journalistic projects, according to "Displaced Voices."

The report identified three main employment situations for displaced Latin American journalists: those who manage to adapt to the workplace in exile, those who struggle to start their own jobs, and those who abandon their professional practice.

"It seems that the trend is that the majority of journalists who go into exile, those who don't achieve that sustainability, which is a very small group, try to become entrepreneurs," Jiménez said. "In some cases, they do it for one or two years, but eventually they end up abandoning their professional practice."

In the digital survey conducted for the report, 32 of the 98 participants indicated they had abandoned their journalistic practice, compared to 64 who continue to work as journalists. However, the majority of those who continue to work do so without adequate compensation, or even voluntarily.

Despite the challenges of sustainability, Pérez and Ángela agree that, although they have considered leaving journalism, their calling to inform is stronger.

“Believe me, I ask myself the same question every day: ‘Why am I still doing this?’ Doing journalism in exile really isn't something you can make a living from,” Pérez said. “But I think I have a conviction. I believe that reporting goes beyond just writing. It's about feeling like you're contributing something to society.”

Venezuelan journalist Diobert Tocuyo (left) misses covering sport events. Since he was forced to move to Chile, he has been unable to practice his profession. (Photo: Courtesy Diobert Tocuyo)

Based on interviews and focus groups, the report's authors identified three main narratives about what it means to do journalism in exile: some see it as a form of democratic activism, others as a mechanism for preserving historical memory, and still others as a way to cope with sadness and displacement.

While Pérez feels that his persistence in continuing to report on sexual diversity in exile is more of a form of activism, Ángela identifies with the idea that her work is a way to contribute to her country's historical memory, especially regarding issues of feminism.

“I'm a journalist at heart. It's like that, right at the surface, to seek out information and share it,” Angela said. “And I do believe that things have to be there, somewhere, written down, or in a photo. They have to go down in history so we don't forget them.”