Almost thirty years after his abduction, Peruvian journalist Gustavo Gorriti is witness to a criminal sentence he considers “fair and conclusive.” However, he said that, in the course of a long and hard conflict, everyone ends up losing.

At the end of November 2021, the National Superior Court of Criminal Justice of Peru sentenced Vladimiro Montesinos, defacto former director of the National Intelligence Service (SIN, by its Spanish acronym), to 17 years in prison for ordering the abduction of Gorriti, a well-known investigative journalist, on April 6, 1992.

The trial of Gorriti's kidnapping began in March 2016.

One of Gorriti's lawyer, Carlos Rivera, told LatAm Journalism Review (LJR) that “it took forever” for the judiciary to determine whether the case should be tried in an anti-corruption or a human rights court.

Finally, when it was decided that it should be tried in a human rights court, the public prosecutor’s office requested 25 years in prison for Montesinos and several former high-ranking members of the Armed Forces who were allegedly involved in the abduction, news agency Andina reported that year.

Vladimiro Montesinos and Alberto Fujimori being interviewed in the news program La Revista Dominical, of América TV, in the lobby of the National Intelligence Service, on April 1999. (Screenshot)

This sentence only adds years to previous sentences that weigh on Montesinos, also a former presidential adviser to Alberto Fujimori (1990-2000). He has been in prison for 20 years and has more than 30 convictions for corruption and crimes against humanity committed during the 1990s, including overseeing the death squad Grupo Colina.

"After my release, I experienced months of extreme tension–and great danger–under the [Fujimori] dictatorship," Gorriti said in an interview with LJR.

Gorriti's abduction immediately followed the self-coup of April 5, 1992, when then-President Fujimori shut down Congress and ordered the military and their tanks to patrol the streets. In addition to Congress, the Armed Forces also laid siege to the buildings of the judiciary, the Court of Constitutional Guarantees, among other State institutions, as well as the headquarters of various media.

As a journalist critical of the government, Gorriti is convinced the goal of his abduction was his disappearance. Moments before his abduction, a group of men dressed in civilian clothes and armed with military weapons raided his house and, after confiscating his computer and several files containing his journalistic stories, he was taken to the SIE (Army Intelligence Service) offices basement, leaving him incommunicado for several hours.

“I was captured in the early morning of April 6 [1992]. At dawn on the 7th, I was transferred from the SIE to the Anti-Terrorism Directorate of the Police. They wanted to release me around noon, but I refused to leave until they returned some of the documents that had been stolen from my house. I then arrived home around mid-afternoon,” Gorriti told LJR.

When Fujimori's self-coup happened, Gorriti alerted Spanish newspaper El País, of which he was a correspondent, that if he did not transmit his dispatch about the coup in the next few hours, it meant he had been detained.

"I also had detailed contingency plans on what to do in such a situation," Gorriti said. His wife followed one of the contingency plans he had devised, and so did his eldest daughter from New York.

These contingency plans also succeeded in getting El País to communicate with Spain’s foreign minister within the first hours of his abduction, the journalist said.

“The Spanish Foreign Minister sent instructions to his ambassador in Peru, the very notable Nabor García, who on the morning of April 6 was already at the office of the then-Minister of Defense [of Peru], adamantly demanding my release and sweeping away the minister’s weak excuses, in which he argued they knew nothing of my whereabouts,” Gorriti said.

There was also pressure for his release from a senior U.S. government official—whom Gorriti had arranged to interview on April 6—through the U.S. embassy.

“Along with that, the international pressure, the voices of protest were many times stronger than what Montesinos and the other coup plotters had anticipated. This led the Fujimori regime to first acknowledge they had captured me, to transfer me to a police station (the Directorate against Terrorism), and then to make an effort to free me as soon as possible,” Gorriti said.

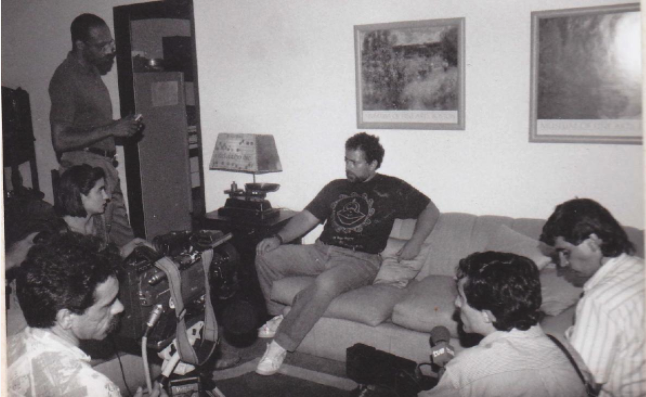

Peruvian journalist Gustavo Gorriti at home after being released on April 7th, 1992. (Courtesy)

Nevertheless, when Gorriti reflected on his abduction, he said that despite this chain of events, it could have had dire consequences. "I was very lucky," he said.

In a conference Fujimori gave to the foreign press shortly after the self-coup, Gorriti rebuked the leader regarding his abduction, while demanding that he return his computer. During the press conference, Fujimori said he knew about the withholding of Gorriti’s files and computer.

The next day, Gorriti said, his computer was returned at a police station.

“They didn’t delete the files, but they did manage to break the login password. Fortunately, the most important information was not there,” he said.

During the 1980s and early 1990s, Gorriti covered the internal conflict unleashed by the forces of the Maoist-oriented terrorist organization Sendero Luminoso, the response of the State and paramilitaries.

Years later, Fujimori became the first former president to be extradited and tried in his own country for human rights violations, according to the Inter-American Court of Human Rights (IACHR).

In 2001, Fujimori resigned via fax from the Presidency of Peru from Japan, where he spent several years until his trip to Chile in 2005, when he attempted to return to Peru. By then, there was already an international arrest warrant on him for the various and serious crimes he allegedly committed during his ten years in power.

Chile ended up extraditing the former president in 2007. One of the extradition arguments of the Chilean justice rested on the abduction of the Peruvian fishing businessman Samuel Dyer and that of Gorriti, according to a report from the Inter-American Court.

After his abduction, Gorriti said, he became "unemployable" as a journalist. "Not even as a correspondent" could he get a job, he said. “Then, I was offered to travel to Washington D.C. as a Senior Associate at the Carnegie Endowment. I took my family along, thinking it would be for a few months. We came back to Peru together nine years later, although in the meantime I came and went several times.”

Regarding the dangers facing the critical and investigative press in Peru today, Gorriti said that although we have much better means and tools of communication than in the past, "the threats are far greater and more complex."

The technologies that exist today, such as the internet and social media, which were supposed to allow us conquer greater knowledge and freedom, have become, to a significant extent, tools of deception and oppression, Gorriti said.

"As in the past, the enemy is also in our midst, only more toxic than before," he said.