Journalist Leonardo Sakamoto, general director of Repórter Brasil, likes to cite the number of hours he traveled by bus to report at the beginning of the organization, in 2001.

"We didn't have any money at the beginning, planes were expensive at the time. So we traveled by bus. I did a story in the interior of Alagoas and it took 48 hours. Another in the interior of Amapá took 53 hours by bus to Belém, another 18 by speedboat, more hours to the interior of Amapá,” Sakamoto recalled in an interview with LatAm Journalism Review (LJR).

Repórter Brasil team in 2015 (Courtesy)

At the time, about ten young people, mostly journalists, got together to form Repórter Brasil with the objective of "bringing out the voice of those people who could not have their stories publicly told, bringing the invisible onto the agenda,” Sakamoto said. They wanted to do something different, not in the sense of opposing the mainstream press, but to complement the coverage of traditional media.

When they traveled, they offered the stories to partner media, but they were not always able to sell the material, and they suffered a loss. Of the initial founders, many worked for other outlets and used their own money to write the articles for Repórter Brasil. "There were times when we lost money," Sakamoto recalled.

From this period of lack of resources and young journalists traveling by bus chasing stories, a lot has changed. The non-profit organization grew, became professional and institutionalized. It won dozens of awards and recognitions in the country and abroad, carried out journalistic investigations and multimedia specials, documentaries, partnerships with national and international media and published scoops that impacted the conduct of companies and public policies. It has also established itself as a reference in human and socio-environmental rights, especially in the areas of combating human trafficking, slave labor and labor violations.

Repórter Brasil celebrates its 20th anniversary on Oct. 9, the date the site was originally launched – in Sakamoto's words, the NGO is today, due to its history in the country, "a grandpa of digital journalism organizations.” To mark the anniversary, LJR spoke with key people at Repórter Brasil to talk about how it works, their way of doing journalism and their plans for the future.

According to Sakamoto, Repórter Brasil is not just a journalism NGO, but "an information hub" on social, environmental and labor issues. With around 25 permanent employees, the organization is divided into four programs: journalism, documentary, research and education.

The journalism arm is the news agency, specializing in large, in-depth and investigative reporting. There is also a kind of independent sub-area, which is documentaries, whose films have won awards at national and international festivals.

"Since 2006, we have been producing feature films about the Brazilian reality, slave labor, workers in slaughterhouses, in the construction of large hydroelectric plants, or those who were massacred by working with asbestos," Sakamoto elaborated.

Another important program is the research program, which carries out field research and produces reports on economic actors. This area is known for the so-called "follow the money” investigations, Sakamoto explained, meaning they follow the trail of money and goods in production chains.

"We tracked more than 2,000 productive units, such as farms, charcoal plants, production sites, construction and industries, showing how goods manufactured with slave labor, human trafficking, child labor, illegal deforestation, attacks on traditional communities, with environmental damage, reach the national and international market,” Sakamoto said.

The research reports produced by Repórter Brasil over the past 18 years have had an impact on policy formulation by the production, banking and financial sectors, as well as by governments and civil society. For Sakamoto, journalism is the main activity of Repórter Brasil, because it encompasses these three areas: the news agency, documentaries and research. Furthermore, the vast majority of the organization's employees are journalists.

Teacher and leadership training in the program Escravo New Pensar (Courtesy)

The fourth branch is education, with several programs, the most important of which is Escravo, nem pensar! (Slave, no way!). Created in 2004, the project has already trained more than 22,000 teachers, social workers and popular leaders in 465 municipalities in 11 states on the issue of preventing slave labor. Repórter Brasil also teamed up with professors from journalism universities to offer an online course to combat disinformation, called Vaza, Falsiane! (Scram, fake!), which received support from Facebook.

For Repórter Brasil's journalism coordinator, Ana Magalhães, the fact that the organization has separate branches that works with journalism, education or advocacy, for example, is something rare in Brazil, but common in other countries.

"I think this is another example of Repórter Brasil’s pioneering spirit," she explains to LJR.

Magalhães says that the areas are financially independent, that is, she is responsible for raising funds for the journalism nucleus. "I have a lot of autonomy. I can hire, I'm the one who manages the resources that I raise myself,” she said. At the same time, all the nuclei contribute to maintaining the administrative sector, which deals with common expenses such as rent, accounting, among others.

This separation of resources also helps ensure the news agency's editorial independence, explains Magalhães. She says that the journalism arm does not participate in campaigns or advocacy. "I think this mixture cannot happen. We try to isolate journalism, precisely to escape this prejudice of being perceived as activists," she said.

Magalhães explains that Repórter Brasil's journalism is "combative and warrior" and, at the same time, very rigorous and technical. "What I do within Repórter Brasil is exclusively journalism, within all the technical criteria of quality and scientific proof, confirmation of the origin of information and the other side. And the proof of our technicality is that we are republished in large outlets in the country.”

Reports made by Repórter Brasil's research team are often used as a reference to improve company policies, and there may be some dialogue in this regard, but this does not affect journalistic production at all, Magalhães says.

"There's an arm of Repórter [the research team] that actually often sits down with companies that are targets of our stories [...] to talk about how they can improve control over suppliers that deforest or use slave labor. It's interesting that there isn't any editorial influence, I don't even notify the other nuclei of the reports that we are going to publish. And I never received any suggestion from another nucleus not to investigate, an interference in my work,” she said.

Journalism coordinator Ana Magalhães (Courtesy)

Asked whether the organization's advocacy work could pose any editorial conflict for journalism, Sakamoto replied, "no, none." And he added that only journalists are used to putting this issue in that way, as an opposition. He explained that Repórter Brasil advocates against slave labor and human trafficking, universal themes present in the Brazilian Constitution. "I would find it very strange to advocate in favor of slave labor. How can you be impartial in the issue of combating slave labor? I don't know," he asked.

He points out that modern journalism was born "hand in hand with human rights,” "in the same soup.”

"Freedom of the press and of expression is one of the human rights. So journalism is born with one of the functions of preserving and guaranteeing that human rights are implemented in a society. If journalism omits this, it is acting on behalf of its own destruction, because without the guarantee of human rights, journalism does not exist. Advocacy for human dignity should be a mandatory condition of journalistic activity," he argued.

Sakamoto emphasizes that it is not the journalist's job, for example, to "take all enslaved workers by the hand and liberate them,” but rather its obligation is to bring quality information to society, so that it can act to realize human rights.

He reinforces that Repórter Brasil is very strict with the other side. "It is even heard more than in many traditional outlet. We follow very heavy parameters [in this]. When you go to investigate, and the other side gives a version that is really strong, the story is dropped. The other side is not pro-forma, it is to try to find out the facts.”

Magalhães agrees that this is a characteristic of Repórter Brasil's journalism. It is not enough to send an email with a request for position, it is necessary to insist and be transparent in the demand. "If the company asks for more time, we usually give it, and we publish the other side in full. For us, the other side is never protocol.”

DNA of Repórter Brasil

Another hallmark of the organization's journalism is investing time and money in investigative, in-depth reporting and fieldwork – although this last aspect has been harmed by the pandemic, Magalhães said.

"It's very common to have a reporter of mine investigating a matter for one or two months just to write a story. Another difference is going to the field, going where no one goes, in places in the Amazon that are very difficult to access and often dangerous. This is very much Repórter Brasil’s DNA, to investigate in the field, even if they are expensive and time-consuming stories,” she said.

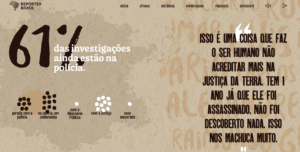

Repórter Brasil has also established itself as a producer of large multimedia specials. According to Magalhães, they try to publish at least one a year. In early 2021, for example, they launched the Cova Medida special, which tracks the 31 murders in rural areas in 2019, the first year of President Jair Bolsonaro's government, to discuss impunity. The investigation found that, a year later, no one had been convicted, and only one case had been considered closed.

Special Cova Medida, from Repórter Brasil (Screenshot)

Magalhães says that impact is one of Repórter Brasil's greatest strengths in journalism, because the reports manage to guide public debate and improve people's lives. Often, the first impact is immediate, right when asking for the other side, she says. This often occurs in investigations into production chains, which reveal, for example, the use of slave labor by some supplier or the association between slaughterhouses and illegal deforestation.

"When asking the other side, if the company is serious, it suspends the supplier. Or suspends it until it investigates [the report's complaint]. So, it's a journalism that fights for this [business] segment to be a little more transparent and sustainable," she said.

Likewise, stories about labor violations usually generate consequences quickly, with investigations by the labor public prosecutor’s office. "In many of the reports, we call a prosecutor to hear about that case and it happens with a certain frequency that they open an investigation."

For example, in August, Repórter Brasil revealed that the army had created a "shame corner" in shelters in the north of the country to confine Venezuelan Indigenous people who had consumed alcohol. Three days after the report, the federal public prosecutor’s office and the Federal Public Defender's Office carried out a surprise inspection of the accommodationand confirmed the existence of the "corner of ill-treatment," as well as collected complaints from migrants and refugees.

Perhaps the most relevant mark of Repórter Brasil's journalism is the themes that the organization covers: human rights violations in the labor and socio-environmental fields. And that encompasses a lot, such as slave labor, human trafficking, deforestation, Indigenous and traditional communities, rural violence, pesticides, production chains, labor rights, just to name a few.

It was these reports that made the organization famous, as Kátia Brasil, co-founder and executive editor of the Amazônia Real agency, recalls.

Repórter Brasil's application evaluates how brands fight slave labor (Courtesy)

"Repórter Brasil is a reference in Brazilian journalism in the fight against work analogous to slavery, which it has reported in numerous articles, the conditions of workers found in degrading situations and violations of rights," she told LJR. The two media are partners in several special reporting projects.

The executive editor says that she stopped buying products from certain companies after reading reports by Repórter Brasil about slave labor.

"I'm sure many Brazilians have changed their view of the world, especially about consuming brands that were investigated for hiring workers in this way." She claims that, just for this coverage, the organization can already be considered "a major Brazilian media outlet,”, and its journalists, "true combatants of human rights violations.”

Attacks and new headquarters

All these investigations, in a country like Brazil, have yielded censorship lawsuits against the organization and its journalists, including an attempted break-in of its headquarters in January and hacker attacks that took the site down.

"Is there censorship against us today? There is. Censorship for publishing public information of public interest. [...] It's attack after attack, but it's part of it. I learned over time, with death threats, being physically attacked, persecuted on the street, to understand the process and not get paranoid. We do an activity that puts us in the spotlight, but also at risk," Sakamoto said.

The anniversary celebration coincided with the purchase of a new, safer headquarters, and will be marked by the production of special content and an institutional campaign. The original idea was to do face-to-face events and a party, but everything was canceled with the pandemic.

Sakamoto says he is very proud of what the organization has achieved over the past twenty years, in a country where, "in many places, human rights is almost a bad word."

"We saw Brazil transform [in this period], but at the same time, regardless of the governments that passed, whether progressive or conservative, the fundamental rights of the most vulnerable groups in Brazil continue to be reviled. So we continue. I think Repórter Brasil's work will be essential in the coming years, because human rights will continue to be a luxury product for the country."