For more than a decade, journalist Carlos Martínez, from the Sala Negra investigative unit of Salvadoran site El Faro, has investigated the phenomenon of violence in Central America. From his experience following gangs, in an attempt to explain the social phenomenon, it’s possible he’s written about every aspect of them.

However, when his colleague, photojournalist Víctor Peña, recently invited him to return to the San Francisco Gotera Penal Center – a prison that Martínez had already written about after its inmates (all members of enemy gangs) converted to evangelical Christianity – he was surprised by what he saw. While Peña was taking his photos, the director of the compound told him about nine prisoners who had openly declared themselves as gay and who, for their safety, were isolated from the rest of the prisoners.

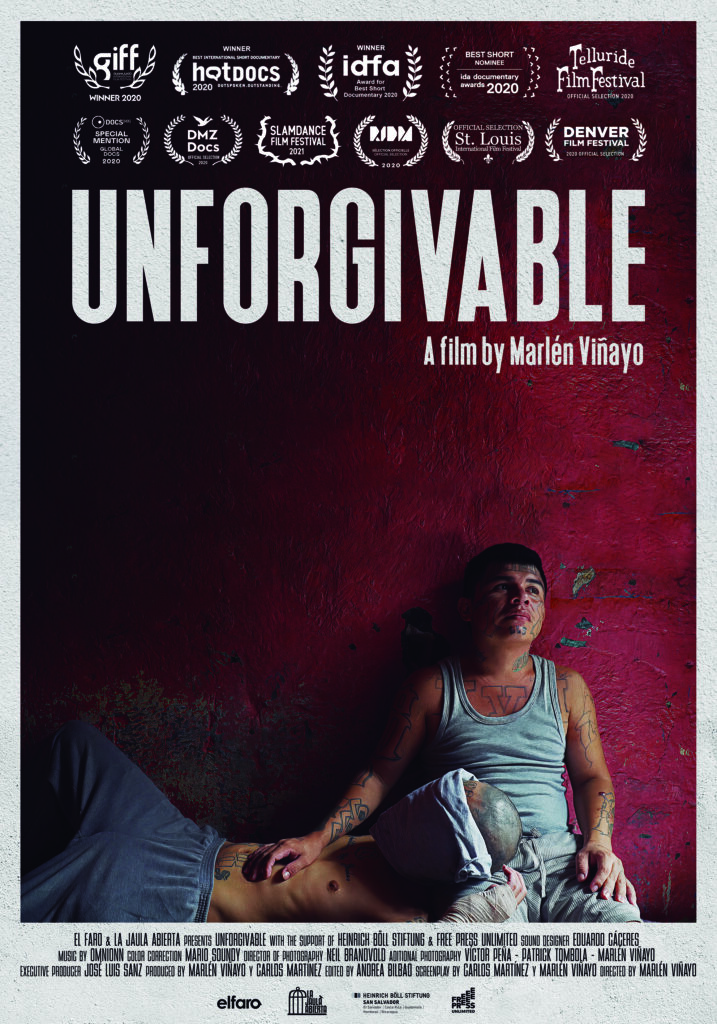

Poster Unforgivable

“One of the first things you learn about gangs is that at the slightest suspicion that one of their members is gay, they kill him. And they murder him in heinous ways,” Martinez told LatAm Journalism Review (LJR). “I was surprised by the fact that there was a cell full of these guys who – you’d assume they should be dead – also lived mixed together with former members of Pandilla 18 in its two factions and with the Mara Salvatrucha, and who also openly lived their homosexuality within the cells.”

The story seemed so complex and "difficult to convey with letters" that literally when he got out of prison he called film director Marlén Viyaño, who is also his wife and who fell "immediately" in love with the project. That was the beginning of “Imperdonable” (Unforgivable), the short film of which Martínez is co-writer with Viyaño and that is winning awards at film competitions and garnering buzz for the Oscars. Beyond this possible achievement, the film tells a different story than what is usually said or told about gangs: a forbidden love in the midst of violence.

Selling the idea to El Faro was not that difficult. El Faro is one of those visionary media outlets, according to Martínez, that bets on the highest possible quality. "El Faro invests a lot in allowing its reporters the time to do the intellectual work that journalism entails," Martínez said. "I understand that for El Faro it is super, super important to be able to narrate the society in which it serves and for this it has considered that it is worth making this type of investment."

In the past, El Faro was a co-producer of works by documentary filmmaker Marcela Zamora. This time, El Faro became one of the producers of the 35-minute short film, which had an estimated cost of US $40,000. La Jaula Abierta, a company owned by Viñayo, was the other producer.

The search for financing was joined by the search for permits to enter the prison for a considerable period. The permission to be there was given for 17 days, but they managed to record everything in 12, all before the pandemic began.

The team rented a hotel near the prison so that they could arrive at 8 in the morning, the time at which visits began, and leave just before the prisoners return to their cells, at 6 in the afternoon. They were long hours, Martínez recalled, which did not end once they left the prison. At the hotel, together with Viñayo and Neil Branvold, the director of photography, they began to do a kind of recount in which they were thinking about what the focus would be, who was the protagonist, how they should show the story, among other discussions.

Marlén Viyaño, directora, y Neil Brandvold, director de fotografía, durante la grabación del cortometraje. (Foto: Cortesía El Faro/ La Jaula Abierta)

"It's very complex, especially taking into account the type of documentary that Marlén makes, which is one in which there are no interviews and it is cinéma vérité," Martínez said. “Because of course, reality tends to reward you when you have enough patience to listen, to be quiet, to ask yourself questions. But 12 days is not a long time for reality to reveal itself and tell you a story that one is able to hear, understand and see. However, to our surprise, things started to happen that we found super interesting from day one.”

After thinking about it many times, having different arcs and narratives, and even proposing up to "80 names" for the film, they decided that the protagonist would be Giovanni. The central plot of the short film is his story and that of his partner, who agreed to appear but without his face being visible because he did not want his mother to know that he was gay. “Let's see, this is a man sentenced to 30 years in prison for murder. He is a murderer […] out of all the things that this man could feel guilty about, it turns out that what embarrassed him above all, being in jail for murder, was for his mother to realize he is gay.”

It’s an aspect that perfectly sums up what the short film is looking for, trying to make complex the debate around gangs, the already accepted conceptions about good and bad, about right and wrong so “embedded in the DNA of Salvadoran society.”

“The short intends to be a kind of reflection of a society, we say, with a very broken moral compass, very, very perverted, let's say. And it is a society, for example, that condemns equally or even more vehemently that a person falls in love with another person and compares it with the fact that someone can be a murderer or that someone can be a member of a criminal structure,” Martinez pointed out.

"Journalism must be interesting"

Martínez is not a filmmaker nor is he looking to switch professions, however, he likes to "play" with other languages. He does so because he is convinced that journalism, in addition to its obligation to be deep, meticulous, truthful, among other characteristics, has "a commandment" that is very important to him but that is usually left aside: to be entertaining and interesting.

“For what is important to become relevant it must be interesting. And that forces us to think of different resources and to play with different languages, to try to speak, to try to babble at least the language of our first cousins who are these other storytellers who also work to look at reality and be surprised by the wonders that usually it has to tell,” Martínez said. "I love what I do, but I am convinced that a 'polyglot' journalist, let's say, is more useful, better serves the society in which he works. I think he also has a better ability to sharpen his gaze and, of course, better opportunities to be interesting and to say things to people in an interesting way.”

The short film has, in fact, managed to interest quite a few others. At present, “Imperdonable” has won ‘Oscar-worthy’ festivals that could open up the possibility of at least reaching the short list for the highly sought-after award in January. For example, the short won as Best Short at the International Documentary Film Festival Amsterdam (IDFA), it also triumphed at Hot Docs of Canada, and in Guanajuato, and managed to enter the final list of candidates for best short for the IDA (International Documentary Association).

Once this stage of festivals and the possible entry to the short list for the Oscars ends, the “Imperdonable” team will seek to concentrate on reaching movie theaters in their country or for some streaming platform to be interested in the product. Martínez believes that especially with these recognitions, the film industry in El Salvador could be encouraged and other people motivated to tell the stories of Central America in a way that they can produce profits.

Giovanni, el protagonista del cortomatraje, y su pareja. (Foto: Neil Brandvold)

“Of course, if you can say the word Oscar along with a movie, you have an audience that is probably more receptive and more willing, let's say, to open their heads and listen to the story you have to tell them. So hopefully, hopefully this thing will be a contribution to that, so that there are people who consider that there are possibilities of making high-quality cinema from Central America and that there are a number of wonderful, splendid stories waiting to be told.”

For now, the Salvadoran public will have to wait a little longer for the situation of recently-opened theaters to normalize a little more in the country, according to Martínez.

Beyond these recognitions and its possible arrival on the short list for the Oscars, for Martínez the reflection that can be given around the role of journalism to tell stories in different ways is also interesting.

“I think these spaces are good for reflecting on the need, I think, to hybridize ourselves and try to bring together the different disciplines, the different languages of the storytellers of the reality that, I believe, is the future. That is, in the search to coordinate languages,” Martínez concluded. “And hopefully there will be more photojournalism, hopefully many animated reports will be made, hopefully non-fiction series will be made on radio, hopefully, hopefully we will be more playful, hopefully that we turn important things into something interesting. And I believe that the path is that attempt, trying to seduce first cousins to be able to tell stories together.”

*This story was updated to modify the headline.