A reporter insists with a source until she persuades him to give a bombshell interview. A team of journalists delves into a pile of papers and disorganized information until they put together a puzzle that points toward powerful interests. An ambitious photographer ignores the privacy of famous people for the sake of a click. A newcomer enters a reality that is foreign to him with the task of writing about it, and ends up reinventing himself.

These characters, in addition to countless others, are part of the imaginary that film, in its almost 130 years of history, has developed regarding journalism and the press. From “Citizen Kane” to “Civil War,” from “Truth” to “City of God,” representations of journalists have appeared in films since the beginning of cinema, whether in works that have journalism as the main theme, or in an ancillary way in plots involving other subjects.

More than 3,200 titles, from silent films to the present, are cataloged in the site Periodistas en el Cine (Journalists in Cinema), which offers the most complete database in Spanish on the representation of journalism on the big screen. This is a project by Argentine journalists Manuel Barrientos and Federico Poore, who created the site based on previous databases, their own research and data from national film libraries.

In May, the site published a ranking of the 200 best films about the journalistic profession and the world of media. It is the result of a survey in which 463 journalists, filmmakers, actors and actresses and academics from more than 20 countries participated. Led by “Citizen Kane’, the top 10 also includes “All the President's Men,” “Spotlight,” “La Dolce Vita” and “The Post,” among others. From Latin America, only “Cidade de Deus,” by Fernando Meirelles, was among the top 10.

Observing how film portrays journalism allows us to think about what values society attributes to the press and its professionals, how these values change over time and how they contradict each other, Barrientos and Poore said in an interview with LatAm Journalism Review (LJR).

"It is very interesting to be able to watch and analyze films about journalism, because they show different facets and ways of practicing it. They also serve to reflect on the profession itself and how the supposed objectivity of journalism is often put in crisis," Barrientos told LJR.

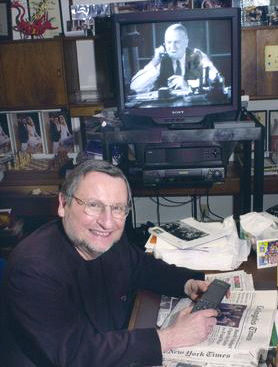

Federico Poore and Manuel Barrientos, the Argentinian journalists behind "Periodistas en el Cine." (Photo: Damian Dopacio)

The two minds behind Periodistas en el Cine are themselves journalists by training, although they currently also work in other areas.

Both studied Communication at the University of Buenos Aires (UBA) and worked in various Argentine media. Barrientos, 47 years old, worked at the political magazine Debate, now closed, and at the newspapers Ámbito Financeiro and Página 12, among others. Poore, 38, started his career at Página 12 and then went to Debate, where he met his colleague. He currently works mainly as a consultant in urban planning, while Barrientos works in the area of institutional communication.

The origins of the Periodistas en el Cine site date back to the year 2000, when Barrientos needed to write a thesis when concluding his undergraduate degree at UBA, he said.

“During those years, I had just seen many films by Nanni Moretti, an Italian director, which dealt laterally with the craft of journalism. I thought about doing a thesis based on how Moretti represented journalism in cinema," Barrientos said. "But my thesis director, Sergio Wolf, who is a documentary filmmaker and was director of the Buenos Aires Independent Film Festival, suggested that I expand on the topic, and I ended up doing my thesis on how cinema in the 90s represented journalism.”

The site emerged almost 20 years later, during the first year of the pandemic. Barrientos invited Poore to create a site with a database and brief film analyses. Afterwards, over the course of three years, the journalists would watch hundreds of films.

“We decided that we were going to watch a lot of films about journalists and that we were going to start analyzing them a little. Between the two of us, we have watched about 700 movies, which is a lot. Then there are obviously entries for films that we know exist, and we haven't seen yet," Poore said.

The site went live early last year. On that occasion, the journalists launched a ranking of 30 best films about journalism according to their own taste.

The collective ranking was organized from March to May this year. According to the duo, more than a thousand professionals linked to journalism or film were invited to participate, and just over 40% actually did so.

Barrientos highlights four types of journalists that film most commonly shows. The first, he says, “there is the heroic journalist, who defends the rights of citizens, joins popular causes and defends democracy. Examples of this type are journalists who investigate and denounce corruption networks, as in the 80s in Latin America, Asia or Africa.”

Examples of these films are "All the President's Men" (1976), which follows Washington Post journalists Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein as they investigate the Watergate scandal; "Under Fire" (1983), set in Nicaragua during the Sandinista revolution, which shows journalists who risk their lives to report the truth and support popular causes; "The Year of Living Dangerously" (1982), which tells the story of a journalist in Indonesia during the 1960s, covering political unrest and popular movements; and "The Killing Fields" (1984), which tells the story of a journalist in Cambodia during the Khmer Rouge regime.

“Another great prototype,” Barrientos said, “is the sensationalist, manipulative or cynical journalist.”]

Poster of "All the President's Men" featuring Robert Redford and Dustin Hoffman, one of the most voted films in the "Periodistas en el Cine" project (Credit: Courtesy)

A classic example is "Citizen Kane,” in which the protagonist, owner of a newspaper, manipulates information for his own ends. Another film that presents this type of journalist is "Mad City," by Costa-Gavras, where Dustin Hoffman plays a manipulative journalist.

Regarding these types, Federico Poore states that they often appear to behave unethically or have exaggerated disputes with colleagues.

“It is very common to think that journalists are hungry for exclusives, so they would do anything to get a story. This is linked to issues that conflict with ethics and exacerbated competition with other colleagues, such as stealing information or a photo," Poore said.

The third type is that of the journalist as a gateway to great stories and characters.

“This type of journalist allows the common citizen to learn about historical figures, places or moments that they would not have access to otherwise,” Barrientos said.

One example is Cameron Crowe's “Almost Famous,” in which a teenage rock fan embarks on a tour with a band.

Finally, the fourth category is the journalist who shapes the values of things in society. This is where the critic comes in, whether they’re looking at sports, film or theater.

“An example of this type is ‘The Devil Wears Prada,’ where a journalist establishes what is valid and what is not in the world of fashion. Another example is ‘Ratatouille,’ where a food critic determines the value of the food. We can also mention ‘Funny Face’ from the 50s, where a journalist defines trends in the world of fashion,” Barrientos said.

He emphasizes that the types are not mutually exclusive: the same film can portray more than one category of journalist, sometimes including the same character, which can be complex and mix behaviors.

“Many times, the same film can have heroic and manipulative journalists, showing the contradictions and diversity within the field of journalism. This reflects the complexity of the journalistic profession and how journalists can play multiple roles in the same story," Barrientos said.

The Periodistas en el Cine project calls to mind the largest global initiative on the subject: the online database Image of the Journalist in Popular Culture (IJPC), created by journalist and professor Joe Saltzman, from the Annenberg School for Communication, at the University of Southern California. Going beyond film, the archive includes depictions of journalists in TV, radio, fiction, commercials, video games and other popular culture.

The initiative came from a personal tragedy, following the death in 1990 of the professor's son, David, from Hodgkin's disease, six days before his 23rd birthday.

“I needed a research project in which I could bury myself in and not think about the tragedy. So for about five years I just stayed in the library researching,” Saltzman told LJR.

The first version of Saltzman's extensive research was published in 1995. Today, it includes thousands of references, from the 21st century to Roman and Greek times, defining journalists as anyone involved in disseminating news and information.

“The database even has Ballads of the 16th century whose songs were essentially news briefs. They would stand outside an execution, write a song about the execution and sell it to the people coming out,” Saltzman said. “Ancient messengers are beginning reporters.”

Joe Saltzman, founder of the Image of the Journalist in Popular Culture database. (Credit: Courtesy)

Saltzman was able to list more than 25,000 films that include depictions of journalists. According to him, around 80% of these works are lost. The most common representations of journalists include investigative reporters, newspaper editors and broadcast journalists, the researcher said. Saltzman noted that these representations often follow technological trends, such as the shift from print to television, and then to digital.

According to the scholar, although many cinematic representations of journalists are based on real events, they often display a “heightened reality,” condensing years of experiences into a two-hour film. He mentions "Absence of Malice," Sydney Pollack's 1981 film, as an example in which several real-life events were brought together in a character's experience.

“Let’s say I'm a newspaperman, and as many newspapermen do, I write scripts for movies. In films, they often incorporate every experience they've ever heard of, their own experiences, and their college experiences spanning over 20 or 30 years, cramming all of these into a two-hour film. If you look at each experience individually, you might say, ‘Well, that could have happened.’ But not all in two hours, not all in one film. It would take 20 or 30 films to cover all those experiences,” Saltzman said.

“So, I wouldn't say these films are not close to reality, but they exhibit a heightened reality with exaggerations. Whether it's negative or positive, these perceptions are always exaggerated, especially the negative ones. No journalist experiences everything; they mostly experience fragments,” he added.

Saltzman highlights three films as particularly realistic representations of a journalist's work: “All the President's Men,” “Spotlight” and “Call Northside 777,” from 1948. These works, says the scholar, portray the hard work the profession requires, which includes hours of research.

“The fact is that journalism can be boring. If you know what you're doing, you're researching—looking at the screen if you're working digitally or going through public records”, Saltzman said.

“Most films focus on drama and conflict. So what do they do? They show the journalist in the newsroom for the first five minutes, then again at the end, but in the meantime, they turn the journalist into a detective solving a crime or exposing corruption, often with their life in danger,” he added.

Some of the representations are problematic, and perpetuate negative stereotypes. Federico Poore highlights films that show female journalists approaching sources sexually in search of information.

Poster of "Blow-Up" by Antonioni, an iconic film exploring the world of photography and truth

"One of the films that did it was 'Richard Jewell,’ a film by Clint Eastwood, where there is a female journalist who I think sleeps with a police officer to get information about how the investigation is progressing,” he said.

Among his favorites are films from the 1930s, such as "Platinum Blonde," one of Frank Capra's first movies, before he made his best-known works. He also likes ‘Mystery of the Wax Museum,’ directed by Michael Curtiz, director of “Casablanca.”

“It is interesting because it has a female journalist, something rare for the time, but very determined,” Poore said.

Barrientos, in turn, highlights films that question the very status of journalism, such as “Citizen Kane,” Brazil’s “Boca de Ouro,” by Nelson Pereira Coutinho, and “Blow-Up,” by Antonioni. In these films, the very status of reality and creation in journalism is questioned, he said.

“I find to be very interesting the films that seem to show a hegemonic view of something and then fracture it, beginning to show a diversity of perspectives,” Barrientos said. “These types of films question the idea of truth, questioning the viewer about what they are seeing and making it clear that one is seeing a representation, and that journalism is also representation.”