The journalistic investigation known as "La Estafa Maestra” (The Master Scam) shook the Mexican political system by exposing a corruption scheme involving members of the cabinet of then-President Enrique Peña Nieto.

Published September 2017 in digital media outlets Animal Político and Mexicanos Contra la Corrupción e Impunidad (MCCI), the investigation’s impact in media and politics attracted the attention of Planeta Publishing, which approached the authors with an offer to publish their work as a book. Journalists Nayeli Roldán, Miriam Castillo and Manu Ureste accepted.

Five years later, Roldán and Ureste published another book, “La estafa maestra: la historia del desfalco” (The Master Scam: The Story of Embezzlement) with a detailed follow-up to the original investigation.

Nayeli Roldán and Manu Ureste, journalists of Animal Político news outlet, published two books based on a investigation that shook Mexican politics. (Photo: Screenshot)

Both books grew the impact of their journalistic work and brought it to audiences other than those who read it in Animal Político and MCCI, in addition to giving the authors prestige and media exposure.

“[Publishing a book] puts you in the media spotlight on the topic,” Ureste told LatAm Journalism Review (LJR). “That, for me, contributes to a greater awareness among the people who follow or read me.”

LJR consulted investigative journalists in Mexico who agreed that publishing books gives their work added visibility. This, they say, is especially relevant in a country where attempts to discredit journalism are constant and where reporters face multiple types of danger and violence.

They said books based on investigative journalism can also mean greater protection against censorship attempts compared to publishing in traditional media, as well as extra income for journalists.

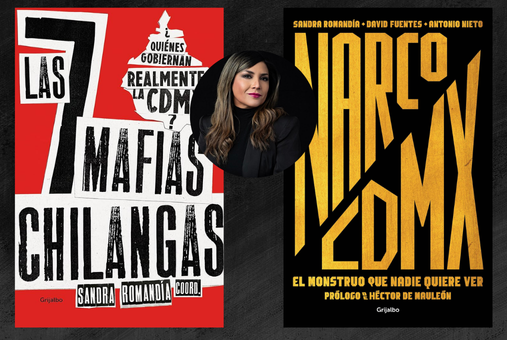

In recent years, investigative journalism in Mexico has been targeted by those in power who seek to discredit it, as well as by political and criminal groups who threaten it, says journalist Sandra Romandía, author of investigative journalism books about drug trafficking groups in the Mexican capital, "Narco CDMX" and "Las siete mafias chilangas.”

“Publishing books to capture nonfiction and journalism stories, and investigations in particular, is a valid channel and format, but also a very useful one for our times, especially in the Mexican context,” Romandía told LJR. “Making these stories into a book, into a necessary, important document that readers can reference and find interesting, is an important option.”

Books offer journalists much broader spaces to explore important topics in greater depth than the day-to-day pace newspaper, magazine, or digital newsrooms allow, said Enrique Calderón, literary director of Grijalbo Publishing, which has numerous investigative journalism books on political topics in its catalog.

“The importance of a book is acquired when it somehow manages to synthesize the chaos of information,” Calderón told LJR. “What we aspire to in order to make a book relevant is that synthesis achieved by journalism, one that can appeal to a reader, seeking a deeper understanding, even if it isn't necessarily newsy.”

Books also give journalists more space to reflect on the topics they investigate. It's this reflection that allows investigative journalism books to bring together in a single document everything scattered about a topic in the media or on social media, Calderón said.

"The main contribution of books is serenity, pausing a bit, and generating some kind of reflection within that same chaos, the speed of information," he said. "What books provide is precisely a space for reflection on the present."

The opportunity for reflection also gives journalists the chance to tap into their creativity and inspiration to create content that goes beyond the informative to become a form of entertainment.

For this reason, narrative journalism and genres such as crónicas and essays are best suited to the book format, the journalists consulted agreed.

“The book lends itself more to publishing crónicas, to narrative journalism, to describing scenes, dialogues, characters… And that makes the information the reader will acquire much more enriching,” Romandía said. “Letting go of the pen, unleashing creativity and inspiration to be able to recount what we saw, what we documented, what we investigated in a more interesting and attractive way for the reader, is one of the positive aspects of producing a journalistic work.”

Ureste said that a journalistic investigation in a book should include hard data, but presented in a more digestible and attractive way for the reader. His book, “The Master Scam: The Story of Embezzlement” begins with a scene narrated as if it were a movie sequence, for which the authors even enlisted the help of a screenwriter. However, he added, both he and Roldán were always careful not to violate journalistic rigor or stray from reality.

Journalist Sandra Romandía has published two books with investigations on drug trafficking in Mexico City. (Photo: Screenshots)

“We were able to adapt all the journalistic work we had to present it in a much more engaging way for the reader,” Ureste told LJR. “I think that's what really catches people's attention. But we're clear that we're not fiction authors; we're journalists, and so there's no room for even a license.”

Even the dialogue scenes featured in "The Master Scam: The Story of Embezzlement" are 100 percent true to the testimony of the people involved in this case, which Ureste and Roldán had access to thanks to their exhaustive coverage of the trials stemming from the corruption case.

“People ultimately want to find out, to be informed, in some way, but if along the way you also present them with a text that's engaging to read, which I believe can be achieved without violating journalistic rigor, then it's obviously much better,” Ureste said.

Calderón, for his part, said that the investigative journalism books under his imprint that are currently doing best in Mexico are those that address topics such as politics, drug trafficking and corruption. But of these, the ones that generate the most conversation are those that include denunciations of those in power.

“That's what we're looking for. If there's, for example, an investigation into drug trafficking, it works when there's a specific accusation against a public authority,” Calderón said. “We insist that our books intersect not only with raising awareness about a sensitive issue, such as corruption, violence, insecurity, etc., but also with some kind of demand for an accountability review of a public figure.”

Reporting on alleged crime and corruption, however, doesn’t come without risk.

Renowned Mexican journalist Anabel Hernández’s investigative journalism books have been the subject of lawsuits. One of the most recent was filed by actress and singer Ninel Conde after Hernández reported in her book "Emma y las otras señoras del narco” (Emma and Other Narco Women) that Conde allegedly had a relationship with drug trafficker Arturo Beltrán Leyva and allegedly collaborated with him to launder money.

In December 2024, it was announced that the actress lost her lawsuit, which demanded millions in damages from the publisher of the book. The legal team handling the case said that freedom of expression prevailed over the right to a public figure's image.

Publishing investigative journalism under a major label has the advantage that authors are supported by legal teams in the event of lawsuits or censorship attempts, something that doesn't always occur in media outlets, much less small or independent ones, Romandía said.

“In Mexico, media outlets and journalists who work independently don't have large law firms to defend us,” the journalist said. “What I see as a positive is that books, in the case of publishing houses, especially the largest ones, do at least have their legal departments, so as a journalist, you know they'll at least support you in a potential lawsuit.”

Romandía said that, although she has never been sued for her books, she has been the victim of threats while researching some of them. However, she does know of colleagues who have received threats of lawsuits in an attempt to stop their investigations.

The journalist said that, in her experience, the protocol in place at publishing houses to verify that all published information is supported by evidence is very meticulous.

“For a book to be published, it means that the information is accredited. There's a process and a methodology to verify that the story was true. Therefore, there shouldn't be [lawsuits], but there are,” Romandía said. “In that sense, there is much closer support.”

Journalist Alejandra Ibarra holds a copy of her book “Causa de Muerte: Cuestionar al Poder.” (Photo: Screenshot from Alejandra Ibarra's website)

Calderón said that publishing houses like Grijalbo are prepared for potential lawsuits in the case of books that could affect third-party interests. There are protocols for legal review of texts before publication and legal support for authors in the event of lawsuits, he added.

“We have an office that helps us read the manuscripts, and these lawyers who specialize in freedom of expression, among other things, point out some potentially problematic passages,” Calderón said. “It's not about erasing information or removing a story, but rather about taking care with the way it's formulated, the way the story is told.”

Alejandra Ibarra, journalist and author of the investigative journalism books "Causa de muerte: Cuestionar al poder” (Cause of Death: Questioning Power) and "El Chapo Guzmán: el juicio del siglo” (El Chapo Guzmán: The Trial of the Century), agreed that books are less vulnerable to censorship attempts because they generally have more visibility than reports in traditional media. This is especially true if the publishers and authors have a certain level of recognition and prestige.

“If we're talking about censorship in terms of physical violence, I think the visibility of the book and the author will play an important role,” Ibarra told LJR. “If the author is already well-known, the publishing house will be large, and the visibility of the book and the author will be enhanced and can serve as a protective measure. It's difficult for someone highly visible, well-known and very famous to be physically attacked.”

Ibarra said something similar happens with censorship attempts through smear campaigns or attacks on the reputation of journalists, which in Mexico often come from the highest echelons of power. The fame and prestige of the authors play an important role, as it's harder for a smear campaign against someone people love and trust to be successful, she added.

The authors consulted agreed that publishing journalistic investigations in books provides prestige and, sometimes, media exposure. But how much of an additional source of income does it represent?

Financial earnings from publishing royalties also depend on factors such as the author's fame and career. But currently, having an audience or a significant social media following plays an important role in the level of income a book can generate, Ibarra said.

“If you have your own audience that follows you, believes you, and likes what you do, they're very likely to buy your books. It's also very likely that a major publishing house will publish and promote you,” Ibarra said. “If you're in that happy place, I suppose book sales can be a significant percentage of your income.”

Journalists who don't fall into that category, and those who publish their investigations with small or independent publishers, often even contribute out of their own pocket to the production process of their books, Ibarra said.

“There are those of us who don't have a significant following and don't publish annual bestsellers. In these cases, the books we work on require a considerable investment of resources from the author himself,” Ibarra said. “When this is the case, royalties can be a valuable additional annual income, but they aren't the main source of income.”

Ibarra said that the more investment is put in building a community on social media, in the investigation itself, and in the editorial process, the better the publishers' resources can be leveraged and the greater the profits for authors.

Romandía said the precariousness of journalists' work in Mexico also extends to the publishing industry. However, while few journalists can make a living solely from publishing books, royalties can be a significant source of income.

“It's extra income, which is always appreciated in an industry that is so precarious,” Romandía said. “It's simply a supporting income that you might not be able to get all at once in your own media outlet or by publishing a report elsewhere. [...] Definitely, at least in my case and in the case of my close colleagues, we don't see making a living from writing journalistic books in Mexico.”

The book “Emma y las Otras Señoras del Narco”, by investigative journalist Anabel Hernández, was the cause of lawsuits. (Photo: Screenshot)

Ureste said the extra workload and time required to publish an investigative journalism book are not comparable to the pay it earns. Therefore, most authors in Mexico do so more for the prestige it brings than for financial gain.

“I remember getting up every morning around 5 a.m. and working until 9:30 a.m. developing the book. And the rest of the day, I did my day’s work at Animal Político,” Ureste said. “The investment of time, effort, resources, etc., that you have to make as a journalist to be able to write a book with the quality standards of Animal Político is far, far greater than the financial compensation you might receive.”

Nonfiction books were the best-selling books in Mexico in 2024, accounting for 43.5 percent of total sales, according to the National Chamber of the Mexican Publishing Industry (Caniem). However, the vast majority of this category were educational and self-improvement books, and only 1.7 percent were books on social issues.

However, the production and sales levels of investigative journalism books have remained stable over the years, Calderón said. This is due, in part, to the fact that over the past 20 years, these types of books have managed to build a loyal following, he added.

“There's a more or less fixed number of these types of books published each year, some with more success, others with less,” Calderón said. “I think they'll continue. They won't grow, but it's not like these types of books will run out in the short or medium term.”

Ureste agrees that there is a niche of people in Mexico who read investigative journalism, but it's not the mass audience that other types of nonfiction books have, he said. However, publishers continue to focus on investigative journalism because of the quality and prestige these books bring, Ureste added.

"Obviously, they're companies and they want to sell books wholesale, but they're also investing in titles that, while they know they won't earn as much, give their publishing label a boost with investigative journalism," the journalist said.

Romandía and Ibarra agreed that publishing these types of books brings investigative journalism to audiences other than those who consume news reports.

"They give you the opportunity to reach readers who probably aren't constantly up on the news or consume media, but who do like access to information, to a well-documented, engaging story that has something to do with them, their environment, their interests, their priorities," Romandía said.