In a democracy, what matters is how rights are exercised in practice, and journalism is a crucial tool in the conception, life and death of these rights.

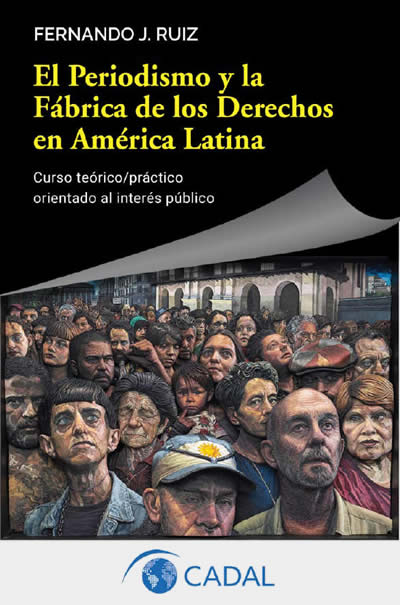

This is one of the central theses of the recently released book “El periodismo y la fábrica de derechos en América Latina” (Journalism and the social fabric of rights in Latin America), by Argentine journalist, political scientist and communications researcher Fernando J. Ruiz.

The result of more than seven years of work, the book, which is available free of charge online, describes itself as a “theoretical-practical course oriented to public interest.”

Ruiz describes the life cycle of rights, from victims' demands to the response of democratic authorities, and explains how journalism impacts each of these stages.

Former president of the Argentine Journalism Forum (Fopea, for its acronym in Spanish) and one of the most respected minds on the region’s press, Ruiz is also an expert on the political and social situation in Latin America. In the book, he makes reference to several countries in the region, from El Salvador to Brazil.

In the interview below with LatAm Journalism Review (LJR), Ruiz reflects on the best and worst of the regional press, how journalists can work in contexts that are far from ideal, and also explains his model to determine whether or not a right is being respected.

The interview has been edited for clarity and brevity.

Argentine journalist and researcher Fernando Ruiz during a public talk (Photo: CUP)

LatAm Journalism Review: First of all, what is this idea of the “social fabric of rights”?

Fernando Ruíz: In democracies, the way to know whether we're moving forward or backward is to look at the number of exercised rights we have—not in the law or on paper, but in the reality of our lives. Each use of those rights has a life cycle where it emerges, and then it can become embedded in our lives forever, or sometimes for a while. They rise and fall, almost like a stock market.

In this life cycle of rights, journalism, in its daily work, can have an impact both positively and negatively.

What I do in the book is describe, in seven stages, how a law emerges until it actually becomes part of our real lives. And I compare how journalism impacts or can impact each of those seven stages.

LJR: And what are the seven stages?

FR: In short, rights emerge when those affected demand them, they reach public opinion, and then democratic institutions and the State transform them into a right and demand their enforcement. In each of these moments, journalism can play a role.

The seven phases are: victimization, when victims perceive an injustice; access to media, when those victims or someone on their behalf gains the attention of journalists; standing, when that voice becomes established in the media; resonance, when the victims' voice is heard; consonance, when that voice manages to spread its indignation to society; formalization, when the legislative, judicial, or executive branches recognize that right; and, finally, the last phase is consolidation, when the State enforces that right.

In short, for a right to be effective and irreversible, its non-compliance must be unacceptable to society, democratic institutions, and even to the so-called street-level bureaucracy. This book analyzes good and bad journalism practices in each of these seven phases, with examples from all Latin American countries.

LJR: You said in the book that "journalism not only informs, but also legislates norms." We are now in a context in which other modes of communication, such as social media, are more powerful than journalism. Is this legislation of social norms still relevant?

FR: Journalism has been somewhat marginalized in recent years, but it still has significant power. Less so than before, but still a key player.

For example, when a company suffers a public crisis and comes forward to defend itself in the public arena, crisis experts generally know that the crisis is over when professional journalism stops covering the issue—even if social media continues to do so. What defines the cycle is whether or not professional journalists participate.

LJR: You argue that journalism schools don't talk much about law. In many Latin American countries, journalism is subordinated to communication in many countries. Should journalism be closer to law and also to political science?

FR: Public interest journalism needs to have much more training in law and political science. Because, in a newsroom, when deciding which topics to cover, many of those arguments have to do with whether the teachers' strike or the police strike is more just, or whether we should cover the story of this family whose son was killed.

There's a discussion that, among other elements, involves the weighting of rights: which is more important and which less, which needs more, which needs less. So, at least public interest journalism should be much more closely aligned with law and political science.

LJR: The editorial line implies a hierarchical approach to coverage of rights conflicts. Can this approach be contradictory? For example, is there a contradiction between economics and environmental issues?

FR: Yes, yes, exactly. The editorial line—especially in countries with a high level of democracy—may not be very clear. For example, the International section may have a more left-wing stance, the Politics section more centrist, and the Economics section more center-right. So, the alignment of rights would be different. But that's also part of an editorial line: how rights are colored differently.

LJR: And how can we prevent cases from becoming highly individualized in this management of rights disputes? For example, for there not to be a lack of understanding of the social factors behind a case of violence.

FR: It's part of journalistic practice to try to incorporate as much context as possible. But clearly, journalism is primarily explained by the individual case. Journalism isn't responsible for the more structural analysis; rather, it absorbs the structural analysis conducted by the academic world to provide context for specific cases.

I understand the meaning of your question, and clearly one must always try to connect the individual case to a context.

LJR: You also talk a lot about communication of the victims. How can we avoid re-victimizing them? Sometimes cases are discussed in a very quick, illustrative and generic way. How can we avoid that?

FR: I dedicate a lot of cases to analyzing this, which seems to me to be a very sensitive point. Because clearly, the strength of rights depends on the victims' or the victims' representative's ability to communicate.

And it's curious, because for victims, communication can be a form of revictimization or it can be a form of empowerment. In fact, in many cases, victims who actively seek communication do so to empower themselves.

In many cases, communication is even very healing for victims. I remember a case of a trial in which the defendant had committed suicide. The victims were allowed to continue participating in the trial to express their testimony because such public communication was healing.

So the relationship between communication and victims is very sensitive. Therefore, the sensitivity that journalists have in their relationship with them is also very important. Part of the rights training that journalists need is also training in sensitivity toward victims.

Returning to a previous question: I think they should also study psychology. And maybe anthropology, too. This brings me to a joke I have here at the university, which says that journalism is the highest level of the social sciences.

LJR: One of the most important points of the book is that journalism is a democratic profession. But when, and in what cases, even under democratic conditions, does journalism fail to fulfill that vocation, or is at odds with it?

FR: First, when it spreads closed discourses that are authoritarian and doesn't question them. When one treats them with moral equivalence compared to other discourses that are democratic.

I really like the expression that journalism is a democratic profession, because journalism is closely related to doubt, questioning, inquiry and investigation. And those are all verbs that, outside of a democratic context, are impossible.

For example, when journalism avoids showing sensitivity to victims and maintains opacity regarding very important groups of victims, this does not contribute to democracy. Because failing to give voice to groups of victims who have very serious grievances can lead those victims to seek other avenues—often, violence.

For example, in Latin America, the situation of extreme and persistent social inequality is intolerable in the medium and long term. It would not be surprising if Latin American democracies faced a crisis because, at some point, these millions of victims grew tired of this situation of neglect and became disruptors of the democratic process.

LJR: What topics do you think are covered most poorly in Latin America today?

FR: The issue of social inequality, without a doubt. I think the type of coverage is tourist coverage; that is, we go visit from time to time, take some photos, but there's no coverage that puts social transformation at the center of the agenda. Perhaps the problem is that social transformation isn't considered possible, and so, since it's not considered possible, there's a resignation: it's assumed that this situation of extreme inequality will continue forever.

Every now and then there's a gesture—some reporting, some indignant editorial—but that topic isn't permanently on the main page.

LJR: Could you briefly explain the VAR model? How did you develop it?

FR: I got that one from the [FIFA] Club World Cup. (Laughs.) It's like that. The democratic process has a stage where the “Voz” (Voice) of those who want to express themselves is built, a second stage in which that voice does or does not achieve social “Apoyo” (Support), and a third stage in which that support does or does not achieve a “Respuesta” (Response) from democratic institutions. If it achieves a response, that right is consolidated.

So, the V, the A, and the R represent those three stages. Journalism can evaluate its performance by observing how it impacts the voice stage, the social support stage, and the institutional response stage—understood as the response of the Legislative, Executive, and Judicial branches, as well as state bureaucracy. This allows one to democratically evaluate their work as a newsroom or as a journalist.

LJR: And how can journalism act effectively in the context of an ambivalent, fragmented state, like the one you mention in Latin America?

FR: And then you have to add an ambivalent press. That is, there's an ambivalent State and an ambivalent press; a press that's often limited, in a "corralito" (playpen); very dependent on its economic or political support, and therefore lacks freedom of agenda. So, the journalists in those newsrooms have very little room for maneuver. That's what's happening today in Latin America.

LJR: So how do you act effectively in these contexts?

FR: When there's little room for maneuver, you have to be as aware as possible of what you can do. For example, I propose a strategy for drug trafficking coverage in contexts where there's very little room for maneuver: working with an indirect agenda.

That is, instead of focusing on describing mafias—which can be very difficult in a precarious press, with an ambivalent State—the focus should be: Why can't the state combat organized crime? What powers does it lack? Instead of investigating crime directly, institutional weaknesses are investigated. That's a safer strategy and one that can have an impact.

We must be aware of the limitations, and within them, try to achieve the greatest possible autonomy to provide the best possible coverage.

LJR: Who is doing the most interesting coverage of Latin America today, in your opinion?

FR: El Faro, from El Salvador. Without a doubt. Because it has been able to reveal, in a very difficult context, the structural violence in El Salvador. Its investigations have spoken with the perpetrators, produced very interesting narrative journalism, with extremely sensitive treatment of sources.

And of course, there are other cases in Latin America. I really like a case in Entre Ríos, Argentina, called Análisis. In a situation of severe economic and political restrictions, it has investigated all political parties and powers with enormous sensitivity.

LJR: And El Faro recently had a controversial case when they interviewed two former gang leaders. In the book, you talk a bit about the risk of moral equivalence when interviewing criminals. What ethical principles should guide journalism in these situations?

FR: The main ethical principle is to be fully prepared for this interview. It's important to listen to the perpetrator, but even more important is that this doesn't re-victimize the victims. Therefore, it's not an interview for everyone: you have to be prepared, and the conditions have to be guaranteed.

For example, when Armando.info in Venezuela investigated one of the military officials most closely linked to torture, they didn't consult him, for obvious reasons.

Another case: the investigation into Judge [Sergio] Moro in Brazil. The Intercept published the leaks without consulting him first, because they feared that publication would be legally halted. It was a real possibility.

So, it must be considered. Contact should be made with the perpetrators only after a thorough assessment of the potential impact: both on the publication, the risk to journalists, and the possibility of re-victimization.

The most disastrous case of an interview with a perpetrator in Latin America was conducted by actor Sean Penn—who isn't even a journalist—when he interviewed El Chapo Guzmán and asked him if he considered himself a violent man. Of course, he replied, "No."

Cover of 'El Periodismo y la Fábrica de los Derechos en América Latina', by Fernando J. Ruiz; the cover features a 2024 reimagining of Antonio Berni’s iconic painting Manifestación, created by Mondongo, the artist duo formed by Juliana Laffitte and Manuel Mendanha (Image: Courtesy)

LJR: Here in Brazil, we had a case where an entertainment show host broadcast a kidnapping live. A boy had kidnapped his partner, and she broadcast the whole thing live. In the end, the boy killed his partner.

FR: Well, that's very serious. We always face a tension in journalism: we have to capture attention. That's undeniable. You can't be a journalist and not want to capture the audience's attention—otherwise, it doesn't work. It's like a professor who can't capture his students' attention.

But if this need to capture attention leads us to turn everything into a spectacle and lose sensitivity toward people, then we are clearly entering into bad practice.

LJR: One last question: What, in your opinion, is the main ethical duty of journalism today?

FR: Maintain sensitivity to ordinary people. In other words, if democracy is the regime most sensitive to ordinary people, journalism is part of the skin of that democratic regime. Therefore, it must never be hardened.