Information vacuums are common in Táchira, a Venezuelan state on the border with Colombia.

In 11 of its 29 municipalities, there are not enough media outlets providing local information, according to the Atlas of Silence by the Venezuelan Press and Society Institute (IPYS, for its acronym in Spanish). Additionally, Táchira has some of the worst internet connectivity problems in the country.

"There are towns in the state where there are virtually no radio stations, not even print media. In fact, the only print media in Táchira is La Nación, and it circulates three times a week," journalist Reinaldo Mora, originally from San Cristóbal, Táchira, told LatAm Journalism Review (LJR).

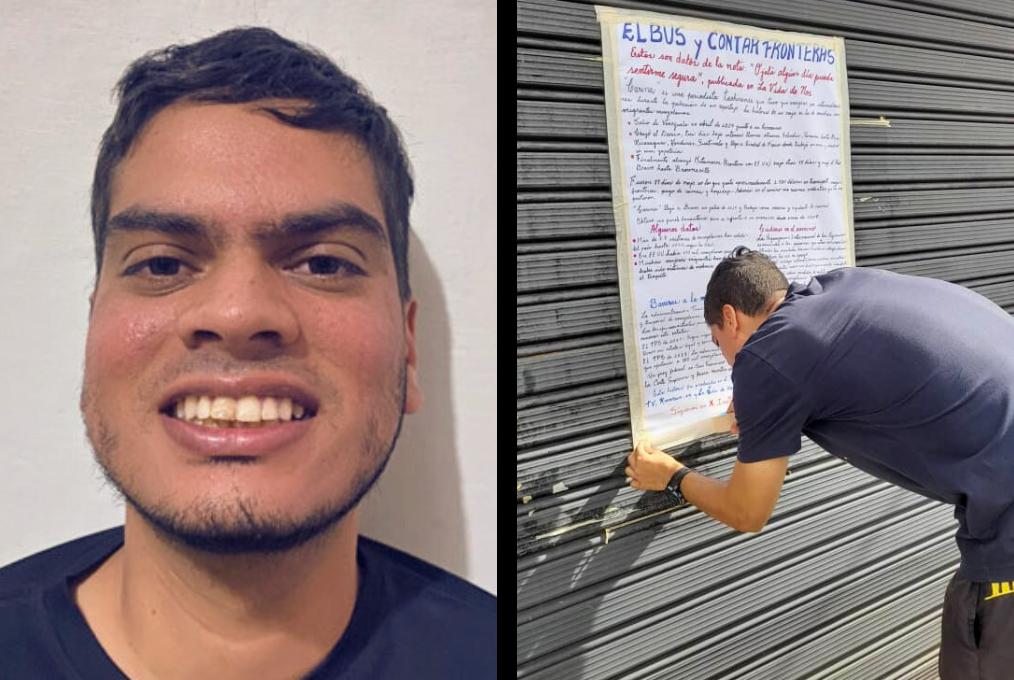

Journalist Reinaldo Mora taped on a street in his hometown San Cristóbal, Táchira, the “flipchart” with his story on the journey of a fellow journalist to the U.S. (Photo: Courtesy of Reinaldo Mora and El Bus TV)

Mora didn’t realize the impact that receiving local information could have on a disconnected community like his until he physically posted one of his reports on a wall in the city. The story recounted the case of "Carina," a colleague from Táchira who was forced to emigrate after receiving threats for working on the border. The article moved the neighbors who stopped to read it. Many confessed to not knowing such situations were happening so close to them, the journalist said.

This experience was the result of Mora's participation in Contar Fronteras (Telling Borders), a training and editorial initiative organized by independent news outlets La Vida de Nos, El Bus TV, and Runrun.es. As part of the program, 16 young journalists from the border states of Apure, Bolívar, Táchira and Zulia learned to report on hyperlocal issues with a focus on service and human rights. They also learned how to distribute stories in different formats, both digital and in person, like Mora did in Táchira.

Contar Fronteras included a series of workshops, mentoring sessions and support over seven weeks between March and May of this year. Organizers said they created it as a way to help address growing information vacuums in border states, where the lack of access to local information takes on different dimensions, given unprecedented migration from the country. Nearly 8 million Venezuelans have emigrated in the last decade, according to international organizations.

“Borders are highly vulnerable spaces. And on the other hand, they are areas of high movement, especially in this country, which is experiencing an unprecedented migration process in its history,” Erick Lezama, senior editor of La Vida de Nos, told LJR. “Dynamics are created there that are worth documenting because they reveal the complexity not only of migration, but of these spaces as a tangible stage for that movement.”

Lezama said the deterioration of the Venezuelan media system, the government's increasing repression of the press, and the country's economic crisis are some of the reasons why many border areas lack consistent hyperlocal news coverage.

“Based on this context, these three media outlets have come together to support young journalists, give them tools, and also motivate them to understand that there are issues, there are relevant stories in their immediate surroundings, stories that one doesn't hear about in the rest of the country,” Lezama said. “Encouraging the production of hyperlocal news helps us understand the country in a more transversal, more panoramic way.”

Contar Fronteras resulted in 13 reports that address complex and under-reported realities. These include stories of parents coping with their children's illnesses from exile, empty schools due to the migration of teachers, Venezuelan migrants deported from the United States to El Salvador, people forced into illegal work, and traditional businesses closing due to violence, among others.

The training component of the program consisted of three modules taught by representatives of the organizing media outlets: hyperlocal narrative journalism, led by La Vida de Nos; data journalism and reports with a human rights focus, with Runrun.es; and content distribution in different formats and offline publishing, with El Bus TV. The program also included a component on security protocols in border areas.

Six of the 13 reports resulting from Contar Fronteras were published on the websites La Vida de Nos and Runrun.es, while all the stories were distributed offline, that is, through analog or in-person methods.

One of these offline formats was the "flipchart," like the one Mora used to distribute his story about "Carina." This is a journalistic tool used by El Bus TV to bring news and relevant information to people without regular access to the internet or digital media. It consists of a sheet of bond paper on which reporters handwrite an adaptation or outline of an article using markers of different colors.

Flipcharts and bus newscasts—in which reporters board public transport and report live news behind a cardboard frame simulating a television—are the main forms of publication El Bus TV has used to combat censorship and informational insecurity since its founding in 2017.

Half of the Contar Fronteras stories were adapted for flip charts, and the other half were narrated aboard buses in the border states, said Laura Helena Castillo, co-founder and director of El Bus TV.

Nuestra reportera Pahola dejó su papelógrafo en una frutería de Maracaibo y allí lo leyó Alexander Perozo.

“Yo tuve que abandonar mi carrera de ingeniería agronómica porque a pesar de estudiarla en una universidad pública, los pasajes, los útiles, las copias y demás cosas que me… pic.twitter.com/oBcz6WvV0A

— El Bus TV (@elbusTV) May 27, 2025

Offline distribution allows stories to transcend publication and achieve face-to-face interaction with audiences, she added.

“At no university is it common for reporters to graduate having done more than two or three stories that have put them face-to-face with people,” Castillo told LJR. “This is the kind of journalism we're interested in, the kind that's done on the street, without intermediaries, that's done face-to-face, and that also has the ability to listen.”

One goal of Contar Fronteras was to teach the selected journalists the importance of making their stories impactful beyond the number of clicks or comments on social media, Lezama said.

“In a country like this, the impact of publication has nothing to do with solving people's problems, because the institutions don't work, because journalism is criminalized,” Lezama said. “One of the most important impacts of this program for me is that we had the opportunity to experience what it means for people to learn about what's happening around them, about aspects of their reality they weren't aware of.”

The offline publishing dynamics that the Contar Fronteras participants learned include the reporter remaining on-site for a while to establish contact with people who consume the news and, if possible, interview them and get their impressions firsthand.

Lezama and Castillo said the conversations that emerged after the stories were published on flipcharts and buses were very satisfying for the participants.

“It's very moving to hear people surprised, grateful for journalistic work, and, above all, how they express the relevance it can have in their lives,” Lezama said. “That's where the public service aspect that a journalist should always possess comes in.”

Castillo mentioned a case in which the impact of a story even had a ripple effect in other states in Venezuela. The report by journalist Isaura Ramos, from the state of Apure, told the story of a teenager whose first menstrual period coincided with her and her family's arrival in a border town after emigrating from their hometown. The family was experiencing poverty that prevented the young woman from accessing menstrual hygiene products.

The story was posted on a flip chart in the restroom of a high school in Apure. Dozens of teenagers came to read the information, sparking a conversation about a topic considered taboo in many schools, as Ramos reported in a social media post.

In response, the flipchart was also published in other states, and as a result, a community leader organized the creation of a menstrual hygiene bank in schools, Castillo said.

Sin buscarlo, Marielvis Zerpa se convirtió en una líder de la educación de su comunidad: es la maestra de decenas de niños, niñas y adolescentes de Cafetera, un pueblo del estado Monagas, donde creció

Ella fue una respuesta a la ausencia de profesores que dejaron el sistema… pic.twitter.com/dBYn1cJm2a

— El Bus TV (@elbusTV) June 5, 2025

“We put a lot of effort into always trying to say, ‘Okay, this is the problem, but how can this be solved in some way?’” Castillo said. “Usually [Contar Fronteras] stories are intertwined with some kind of solution or possibility.”

Throughout June, Runrun.es, La Vida de Nos, and El Bus TV shared their experiences publishing Contar Fronteras stories offline on their social media channels.

The public's interest and reactions to the Contar Fronteras stories demonstrate that it's possible to connect with audiences by addressing topics they can relate to, even those who tend to avoid political news out of boredom or distrust, Castillo said.

“People are already tired of the news and reject it,” the journalist said. “But when you suddenly choose topics that touch people in a different way, and you also break into their lives, you can reconnect with those communities. This program was quite revitalizing for us.”

Although border regions are characterized by very hostile realities, topics like those featured in Contar Fronteras allow for journalism that isn't marked by the political stigma and polarization that exists in most news outlets in Venezuela, Castillo said.

“If there's one thing people in these underserved areas appreciate, it's information, learning things they didn't know, and seeing how they can connect with others,” she said. “There's also your ability to choose topics, like period poverty, which isn't directly a political issue, but it is a completely political issue.”

Lezama said the media outlets involved are currently seeking funding to make a second edition of Contar Fronteras a reality.