For nearly two decades, Alex Sandro dos Santos lived by an unspoken rule of Brazilian sports journalism.

He called games, interviewed players and parsed lineups, but never revealed a question at the heart of his passion for soccer: Which side was he on? He never slipped on a club jersey, never declared an allegiance.

That changed in March 2020.

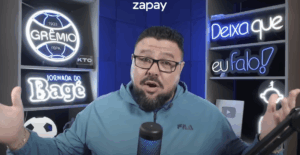

Appearing on a popular soccer talk show in the southern state of Rio Grande do Sul, dos Santos — better known by his nickname, Bagé — pulled on the blue, black and white jersey of the storied club Grêmio.

“From now on,” he told viewers, “we have a transparent relationship.”

His then-boss had warned him. “This is a decision that cannot be reversed,” Bagé recalled him saying. But the move drew more than 90,000 views on YouTube, and set him on a new path.

Five years later, Bagé’s gamble has transformed his career. He has built a following of 170,000 on Instagram and 250,000 on his own YouTube channel. He has a network of 15 collaborators who help him livestream games, post commentary and manage social media and market a brand that blurs the lines between fan and journalist, he said.

“Disclosing your team used to be taboo, but today it’s not anymore”, he told LatAm Journalism Review (LJR). “There were only a few who did it, but this new social media landscape gives you the freedom to do that.”

Many Brazilian journalists – primarily covering soccer – are embracing their fandom as a way to adjust to an evolving business model that entangles journalism, engagement, entrepreneurship and sponsorship from gambling companies. They’ve become known as “Identified Sports Journalists,” or ISJ for the title’s initials in Portuguese, because they publicly identify with the club they support.

Alex Sandro dos Santos, aka Bagé, is an identified journalist and supports Gremio. (Photo: Courtesy Bagé)

The results, at least in Rio Grande do Sul, have been a success. A recent story by a current journalism graduate at the State's Federal University (UFRGS) said the biggest identified journalists in the state had about as many followers as the social media accounts as the state’s two main teams – almost one million.

With the continuous news cycle and the need to be in front of a camera, it became more difficult for journalists to be private about the clubs they support, a passion that for most came before their own professional career.

Paulo Vinícius Coelho, aka PVC, has covered sports for more than three decades. His colleagues and audience know who he roots for, Sociedade Esportiva Palmeiras, but he considers himself a neutral journalist and said he only discloses his team when it is integral to a conversation.

“I have always avoided that old trick of pretending to support a tiny club or a club from another country to hide the fact that you are passionate about a club here”, he told LJR.

He’s aware of the market’s tidal changes, and launched himself onto Instagram to capitalize on social media’s potential, he said. But he warns: “What ends up happening is that your passion turns into an income, but some still say it's just passion.”

Even legacy media companies like TV Globo are creating identified spaces for journalists to express their passion separate from the general newsroom. Quetelin Rodrigues, 36, started as a neutral journalist, but chose to disclose her club, Grêmio.

Currently, she writes an identified blog about Grêmio for TV Globo’s sports outlet Globo Esporte and participates in several commentary programs with traditional and identified journalists. “I never would have imagined I would have become identified with my club. I thought I would be neutral forever,” she told LJR.

Other young reporters have also embraced this path, but not without questioning what it means to practice journalism from a partisan angle.

Leonardo Garcia Gimenez, 25, a reporter for the identified outlet Central da Toca, which covers Cruzeiro Esporte Clube in the southeastern state of Minas Gerais, distinguishes between identified journalists and influencers. He said identified journalists seek to inform, while influencers seek to cheer and give an opinion, even if they're not well informed.

“We definitely root for our team, but above all, we provide news coverage,” Garcia Gimenez told LJR. “Influencers, on the other hand, don't have this concern. They just cheer, whether they are well informed or not. But in a way, the target audience itself recognizes the difference”.

Still, even for identified journalists who set themselves apart from influencers, the pursuit of engagement remains a complicated issue.

Quetelin Rodrigues, is an identified journalist working for O Globo and supports Gremio. (Photo: Courtesy Rodrigues)

“Since these ISJ’s income depends precisely on engagement and what is converted into content, it is difficult not to try to follow a path that guarantees this success,” Josué Seixas, a Brazilian sports freelancer for outlets such as The Guardian, Daily Mail, told LJR.

Seixas notes that journalists with an established track record in traditional media can maintain a more sober profile, but he warns that those just starting out often need to take a “different” approach to win over the public. “This means that, if not with information or access, it will have to be based on some kind of performance,” he said.

That is one of the core criticisms made by Carlos Guimarães, 46, a sports editor at Rede Bandeirantes TV and a professor at the Escola Superior de Propaganda e Marketing (ESPM). A sports journalist of almost 30 years, he said he sees identified journalism mostly as spectacle and performance.

“If his or her team is in a big match and this ISJ gets a scoop that might inflict damage to the club in any sense, he might choose not to publish it,” he told LJR.

States with fewer big clubs, like Rio Grande do Sul and Minas Gerais, tend to have a more polarized sports viewing public, and have bigger issues with how identified journalists conduct interviews with players and staff of the club they love. Last year, a Brazilian coach from a Rio Grande do Sul club loudly complained about these new types of journalists, calling them extremely disrespectful in their questioning during a press conference.

Another challenge for identified journalism is the pervasive role of betting companies, some of which sponsor both the clubs and the outlets that cover them.

Renato Barros, 34, works for the Timbucast podcast, covering Clube Náutico Capibaribe in the northeastern state of Pernambuco. The betting company Esportes da sorte sponsors both the team and the podcast. But there is no direct relations between the team and the podcast, and the sponsor doesn’t try to exert any influence over the content of the podcast, Ribeiro said.

“We've never been subject to any kind of restriction, any kind of request not to talk about an issue”, Ribeiro told LJR. “Quite the opposite, we have a lot of freedom to talk about everything in a relaxed way.”

However, it’s challenging to draw a clear picture of betting companies in the evolving sports journalism landscape, said Samira de Castro, president of the National Federation of Journalists (FENAJ). It’s essential for outlets to be clear with audiences when a story is sponsored or has commercial ties, she told LJR.

“This requires a critical look at their relationship with the press,” she said. “We need to ensure that news coverage is guided by transparency, without confusing information with advertising.”

Today, all of the top-tier 20 clubs in Brazil are at some level sponsored by betting companies. Meanwhile, traditional outlets are seeing declining revenues as identified outlets are growing.

According to FENAJ, media employment peaked in 2023 with more than 60,000 jobs, and by 2023 had dropped by 18 percent, given economic downturns, the pandemic, technological developments and evolving business models.

At the same time, the country sees a skyrocketing number of bets, and issues like addiction are becoming a nationwide issue.

As betting companies become more deeply embedded in Brazilian soccer, journalism around the sport is also evolving. Journalists now face new revenue models as well as growing scrutiny over how their work is perceived.

“Identified journalism places the journalist in the role of reporting facts, but clearly rooting for the subject they are reporting on. This can lead to complications,” said sports editor Guimarães, adding that the ideal would be to have a certain distance from the things you cover. “When you are too close, you compromise yourself with issues that undermine your credibility.”

PVC, who has written 11 books on sports journalism, said the field is in need of a new code of ethics. “The journalist may be wearing a jersey or a suit and tie, but accurate information is non-negotiable,” he said. “And that's a point that's being lost sight of. People have begun to understand that this kind of identified journalism helps to increase confusion, and people are starting to think that it's impossible to have unbiased information.”

For Rodrigues, even though sometimes she just wants to cry after her team has a bad game, the current perspective is a positive one. “I experienced both sides as a journalist, but today I live in the best world, right? I am in my profession, doing what I love to do and openly talking about the team I love. Of course there is a good side and a bad side to that, but the good is this freedom.”