A year into her presidency in Mexico, Claudia Sheinbaum has shown a contrast with her predecessor in her approach to the press. However, she retains some characteristics of the communication policy of former president Andrés Manuel López Obrador, during whose term watchdog journalism declined, according to British historian Andrew Paxman.

Although violence and hostility toward journalists in Mexico persist – at least eight journalists have been killed so far during Sheinbaum's term – the president's rhetoric is significantly less aggressive and confrontational, Paxman said.

“She is generally avoiding being critical of independent journalists and independent media,” Paxman told LatAm Journalism Review (LJR). “This is a major rhetorical shift which I'm very happy about and I think we should acknowledge that.”

However, he added: “The situation is still very grave on the ground.”

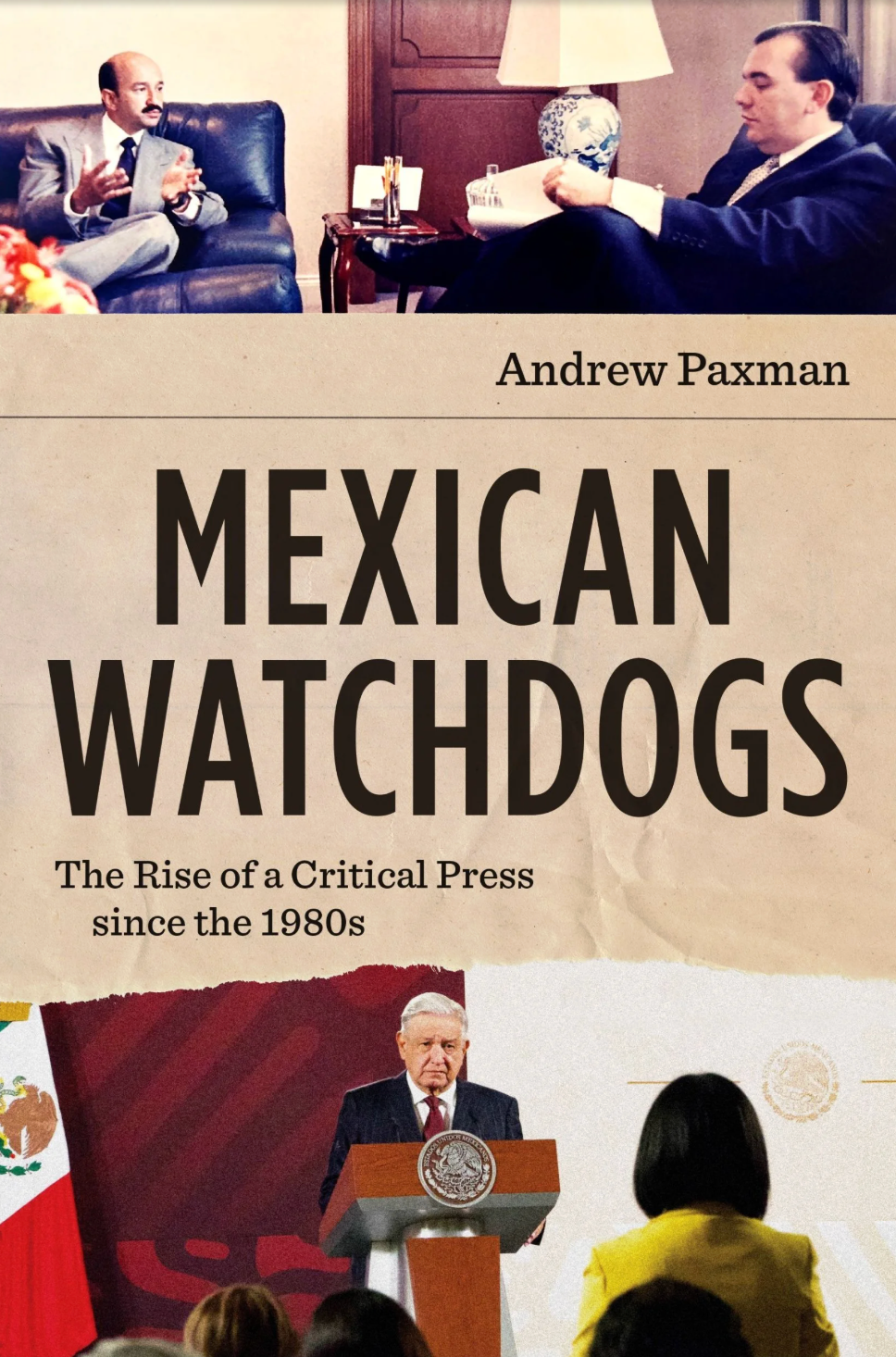

In his new book, Paxman writes about the opening and evolution of the Mexican press toward critical journalism since the 1980s. (Photo: Courtesy)

In his new book, “Mexican Watchdogs: The Rise of a Critical Press Since the 1980s,” Paxman writes about the opening and evolution of the Mexican press toward political pluralism and critical and investigative journalism since the 1980s.

"I think one key to understanding the current relationship or the recent relationship between [López Obrador and Sheinbaum's political party] Morena and the press is to know how journalism was practiced in Mexico for most of the 20th century,” Paxman said.

The author, who is currently a professor of history and journalism at the Center for Research and Teaching in Economics (CIDE, for its Spanish acronym) in Mexico, explains in his book that watchdog journalism was able to flourish in Mexico starting with the presidency of Carlos Salinas de Gortari in the 1990s, due to the convergence of several political and economic factors.

In his attempt to project a democratic image during North American Free Trade Agreement negotiations with the United States and Canada, Salinas de Gortari reduced press controls and adopted a more tolerant attitude toward criticism, Paxman explained. At the same time, increased private advertising investment, the liberalization of the newsprint market, and the support of visionary businesspeople fostered the emergence of more independent, professional and modern media outlets in Mexico, he added.

This watchdog journalism had a boom during the administration of Enrique Peña Nieto, from 2012 to 2018, the author said, but its decline began when the nationalist and populist left-wing party Morena came to power in 2018 with its founder López Obrador at the helm.

The arrival of López Obrador to the presidency represented a radically new policy towards the press, Paxman said.

Until 2018, investigative and watchdog journalism was practiced with relative freedom, the author said. But measures such as the radical cut in subsidies in the form of government advertising, the constant discrediting and stigmatization of media outlets and journalists, and the imposition of the news agenda from the National Palace, contributed to the weakening of that journalism, Paxman added.

Several critical media outlets suffered significant cuts in official advertising, Paxman said, while others more aligned with López Obrador received generous subsidies that consolidated them as de facto propaganda organs, he added.

Paxman believes that the financial relationship between the government and the media has not changed much under Sheinbaum's presidency, and believes that support for pro-government media continues.

The cuts in government spending during López Obrador's administration were compounded by a decline in commercial advertising. The near-zero economic growth recorded during López Obrador's presidency impacted the advertising sector, Paxman said.

Many journalists who previously did watchdog journalism for major newspapers became independent and continued to publish their investigations individually, mainly through books, Paxman said.

The book format has become an important vehicle for investigative journalism. Journalists such as Anabel Hernández, Diego Enrique Osorno and Nayeli Roldán have published investigative reports in books that have shaken public life in Mexico.

In the last 15 years, journalistic collectives have also emerged that publish watchdog journalism on digital platforms. However, they often struggle to secure funding, Paxman said.

“La Mañanera” is the popular name for the morning press conference that López Obrador instituted when he was Head of Government of Mexico City and reinstated as president. It is a daily meeting with journalists at the National Palace, where the president sets the day's news agenda, making it difficult for the media to compete, Paxman said.

“La Mañanera” became known primarily as the president’s main platform for discrediting, attacking and intimidating opponents, including journalists. “Opposition” press, “conservative” press, “chayotera” (corrupt) press, and “fifi” (elite) press were some of the most common terms López Obrador used to denigrate critical media outlets.

Paxman said that with this rhetoric, López Obrador was sending —intentionally or unintentionally— the message that journalists were the enemy. The author believes this may have been one of the reasons why the number of journalists killed did not decrease during his administration.

President Sheinbaum continues to hold the daily morning press conferences started by her predecessor, although the attacks against the press during them have diminished. (Photo: Screenshot from the YouTube channel of Mexico’s Presidency)

“I think the way that his anti-press rhetoric would have been interpreted by certain corrupt politicians and by certain criminal organizations is ‘we have a green light to carry on bumping off journalists who are poking their noses into our business,’” he said. “So there are various sorts of rhetorical prompts that I think are allowing corrupt actors in the states to think ‘if I kill a journalist I'll probably get away with that.’”

During Felipe Calderón's six-year term, which began the war against drug cartels (2006-2012), 48 journalists were murdered for reasons related to their profession, according to figures from Article 19. Under Peña Nieto's administration, 47 journalists were killed. Under López Obrador, the number remained the same.

President Sheinbaum continues to hold daily morning press conferences. And although the attacks against the press have lessened, she retains Jesús Ramírez Cuevas, former communications coordinator for López Obrador and considered by many to be a co-creator of these conferences, as one of her closest advisors.

One of the narratives that originated in "La Mañanera" is that journalists are by nature "chayoteros," a term that was popularly used in Mexico to refer to reporters who received bribes from their sources, something that Paxman said rarely happens nowadays.

“But the idea that journalists are on the take has remained very much in part of the way that the public perceives the press, because it went on for so long,” Paxman said. “If a journalist is criticized as a chayotero, whether that's true or not, it's a resonant criticism because the public in general perceives that historically journalists have been chayoteros.”

While watchdog journalism plummeted during López Obrador's presidency, the popularity of influencers and vloggers with pro-government messages skyrocketed, Paxman said.

These types of communicators, characterized by sensationalist content and "clickbait" style headlines, gained a lot of influence from the beginning of the six-year term and served as an echo chamber for the messages of "La Mañanera," the author said.

“If AMLO criticized a particular journalist, such as Carlos Loret de Mola, who's a very prominent multi-platform journalist chiefly active on radio and YouTube, or if he criticized Ciro Gómez Leva, Enrique Krauze, or even Carmen Aristegui, they [vloggers] would amplify that criticism on their YouTube channels, their tweets and Facebook accounts,” Paxman said.

Many of those vloggers benefited from front-row seats at "La Mañanera," the opportunity to ask the president questions and easier access to government politicians, Paxman said.

While many of these influencers have been accused of being on the government payroll, Paxman believes that most do not need government subsidies, as many of them earn between 50,000 and one million Mexican pesos per month (between US $2,700 and $54,000) from social media advertising.

“I use the term monetizing their stridency,” Paxman said. “The more outrageous they are, the more traffic they're going to get. And that traffic means revenue.”

In his book, Paxman argues that there is a triple threat to press freedom in Mexico: the violence of drug cartels, the crisis of media sustainability and the discretionary use of official advertising.

In that context, journalism done in the states, outside the capital and major cities, is the most threatened and faces the greatest obstacles, Paxman said.

In “Mexican Watchdogs,” the author argues that there are two clear trends in journalism in Mexican states: self-censorship due to threats from crime and the return of “official” media outlets that live at the expense of the government.

Andrew Paxman is a British-born historian and journalism professor, whose work centers on Mexico’s media, politics, and modern history. (Photo: Paxman's X profile)

In many states where organized crime has a strong presence, more and more local media outlets have decided to stop covering organized crime because of the danger it represents, Paxman said.

“There are areas of Tamaulipas, Michoacán and other states where there's a strong presence [of organized crime] where there are zones of silence,” he said. “And they managed to continue doing a good job as journalists despite everything.”

This is in addition to the fact that, traditionally, state governments tend to financially benefit media outlets that treat them favorably, which, Paxman said, became more evident under López Obrador's administration. The author sees an increasingly marked return to pro-government coverage.

“For example, [the state of] Puebla in the 1990s had three pretty strong independent newspapers. Today I don't think it has one,” Paxman said. “There are two good news websites in Puebla, which are E-Consulta, which is a daily news service, and Lado B, which is kind of a news magazine. Those are good independent media, but the print media and other online media are basically all living off the state.”

In his book, Paxman proposes a system of subsidies for journalism in the states of Mexico, like the one that existed in the 1960s and 1970s in many European countries whose governments realized that many small-town media outlets were at risk of disappearing.

This, he said, is supported by academic research that also shows that local governments are less efficient and more prone to corruption when local media disappear.

“These institutions are overseen by a pluralistic board and they've cultivated a tradition over the decades of giving subsidies in a non-partisan fashion in order to ensure the survival of print media, and I imagine digital media these days are also getting subsidies,” he said. “I would like to see something like that set up in Mexico.”

The international English edition of Paxman’s book was released on Oct. 28, but a Spanish version that delves deeper into López Obrador and Sheinbaum will be available in summer 2026, the author said.

This article was translated with the assistance of AI and reviewed by Teresa Mioli