When the peace process with the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC, for its initials in Spanish) began in 2015, the team at the country's Foundation for Press Freedom (FLIP) wanted to measure the armed conflict's impact on local journalism.

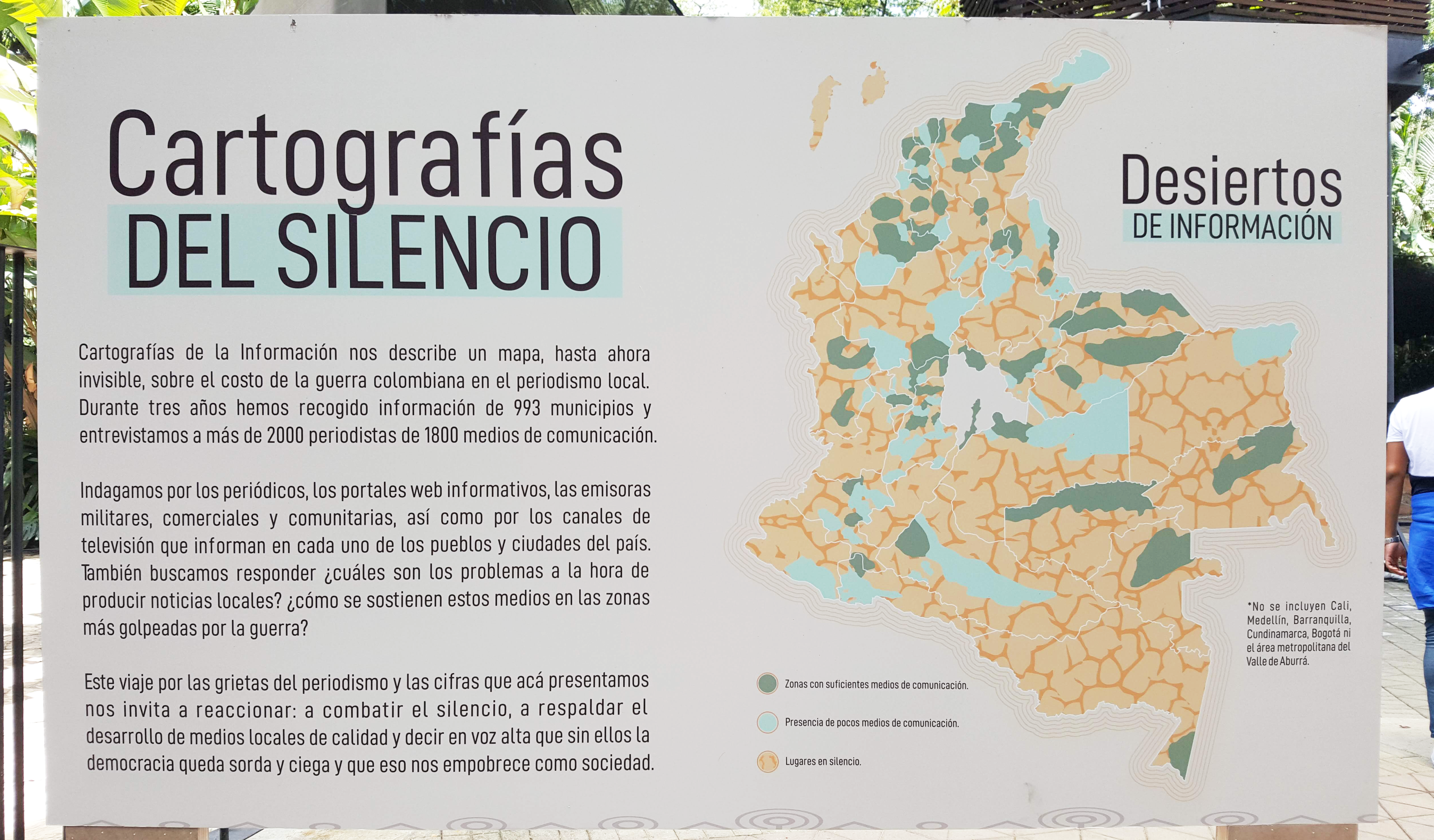

Among its findings published in the report “Cartografías de la información” (Information cartographies), is that 8.8 million Colombians live in zones of silence, meaning they do not have access to local information.

Exhibit of the Cartographies of Silence report at the Gabriel García Márquez Festival in Medellín. (Teresa Mioli/Knight Center)

Exhibit of the Cartographies of Silence report at the Gabriel García Márquez Festival in Medellín. (Teresa Mioli/Knight Center)For the report, the team took a look at the country’s media ecosystem.

“How many had closed, where there were no media,” said Jonathan Bock, researcher of the FLIP Studies Center and project coordinator, told the Knight Center. “And we began to test this project in the departments that has been most affected by the conflict, such as Arauca, Putumayo and the southern area of the country, and what we found is that there were many municipalities where there were no media.”

After this initial look, the team saw it was a problem spread across the country.

“Maybe there is a station that only produces music, or a television channel that only offers movies, but does not give local information,” he explained.

In Colombia, 585 of 994 municipalities mapped by FLIP are “in silence.” Further, according to Bock, media are concentrated in capital cities.

“The war between the armed actors left, in the majority of municipalities in the country, a patent fear to speak openly about issues of public interest. These places continue to be information deserts,” reads part of an exhibit that launched the report at the 2018 Gabriel García Márquez Journalism Festival in Medellín.

The team spent three years gathering information from close to 1,000 municipalities in order to produce the report. They also interviewed more than 2,000 journalists from 1,800 media outlets.

There is the case of San José de Uré in northern Colombia, where there are only two media: a bulletin board run by a community leader and a community radio station that has unsuccessfully sought to be legalized. According to FLIP, in the town, there are things people don’t talk about: paramilitaries, drug traffickers, bacrim [bandas criminales], hitmen and others.

In Jericó, one radio station relies heavily on advertising provided by a local mining company, according to the report. By contrast, a local newspaper that does not receive advertising from that company, or others like it, cannot afford to pay its employees.

During the long-running armed conflict, radio stations run by the security forces would arrive in a town for military and marketing purposes. They are used to demobilize the guerrillas and boost morale, as the FLIP report explains. And in many towns affected by the armed conflict, they are the only source of local information on the radio.

The FLIP team discovered two common characteristics for the zones of silence: a lack of resources for equipment and operation, and censorship. In the case of the latter, FLIP says certain interests force censorship and that journalists also keep quiet because of the advertising they need to survive.

Beyond looking at areas without access to local information, the exhibit discusses conflict between military and community radio stations. The two are unequal in terms of financing, infrastructure and institutional support, according to FLIP. Additionally, it says military radio stations – of which there are 108 stations – have been thought of in terms of supporting the armed struggle, not providing information to citizens. And in some instances, community radio stations have been stigmatized, according to FLIP.

Exhibit of the Cartographies of Silence report at the Gabriel García Márquez Festival in Medellín. (Teresa Mioli/Knight Center)

Exhibit of the Cartographies of Silence report at the Gabriel García Márquez Festival in Medellín. (Teresa Mioli/Knight Center)The report also looks at the status of internet connection in the country and its impact on media. “In 12 departments in Colombia, internet speed is between 60 and 100 times slower than in Bogota,” the exhibit explained.

For certain areas, this means launching a digital media site is impossible, the report emphasized. As an example, only 171 of the 1,805 media investigated were digital.

And finally, the report looks at the financial conditions that journalists work under. Of the 1805 media analyzed, “340 pay less than a minimum wage.”