*This post has been updated.

Eleven media outlets from Latin America worked on the latest transnational investigation spearheaded by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ). The Implant Files, released on Nov. 26, looks at the global medical device industry and the regulation (or lack thereof) surrounding it.

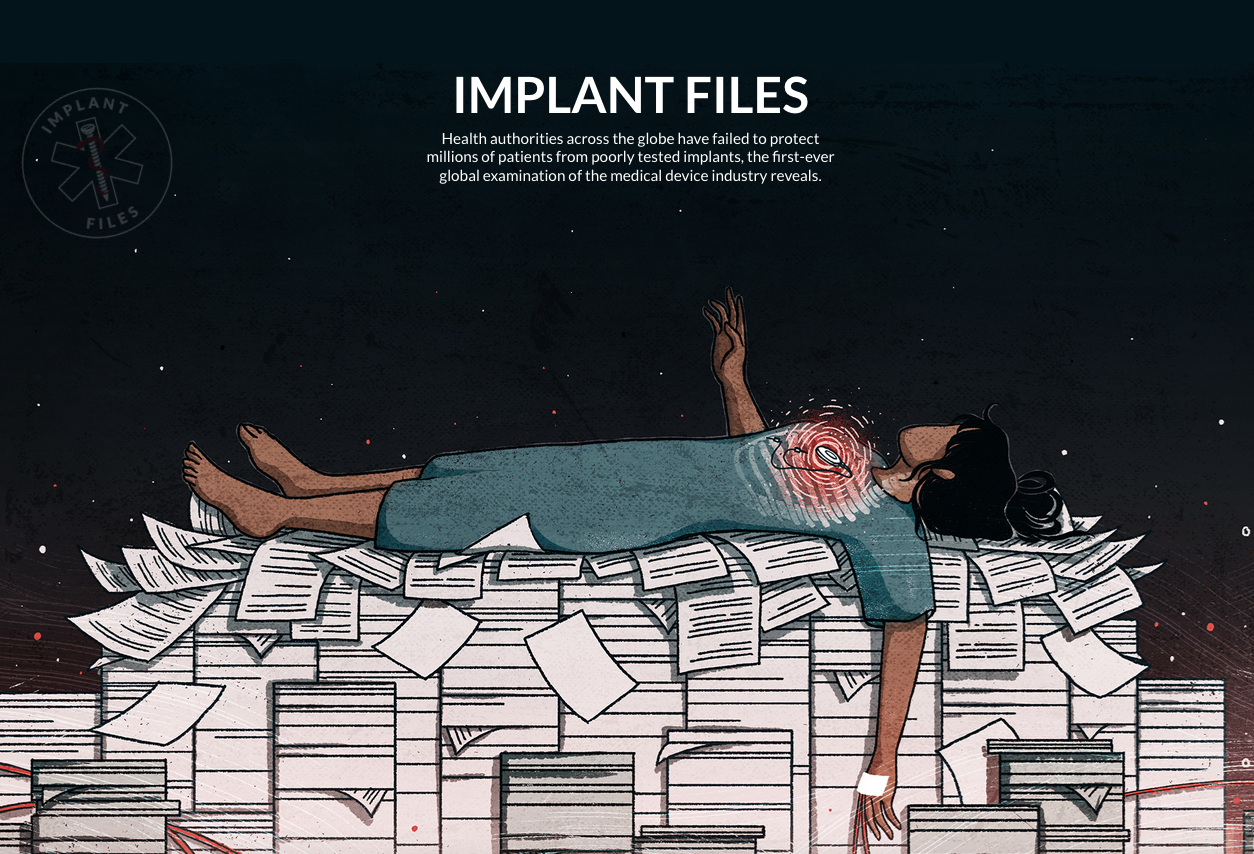

The Implant Files is a transnational investigation led by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ). (Screenshot)

The Implant Files is a transnational investigation led by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ). (Screenshot)The project was inspired by reporting done by Dutch journalist Jet Schouten. In 2014, she and a team presented regulators with a fake vaginal mesh made from a net bag that carries mandarin oranges. The intent, as the Columbia Journalism Review (CJR) reported, was “to show how easy it can be to get medical devices onto the market in Europe.” None of the private “notified bodies,” which are in charge of approving devices, questioned the “alarming” safety data Schouten submitted, CJR added.

To report the Implant Files investigation, ICIJ contacted investigative reporters with experience working on health topics. They looked at what the data and initial research showed and then began to involve media allies from countries where they found data or the market was large, said Emilia Díaz-Struck, a Venezuelan journalist, as well as data editor for the Implant Files and Latin America coordinator at ICIJ, told the Knight Center.

Thirty-nine journalists from Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Costa Rica, Ecuador, Mexico, Peru and Venezuela were among the more than 250 professionals who worked on the project, which took a year to plan and another year to finish, according to ICIJ.

Within the larger ICIJ collaboration, Latin American journalists involved in the project also worked together.

“Latin American journalists shared a common chat and had a special group to share thoughts, questions and ideas. They coordinated the translation of stories and also helped each other in the process of getting a better understanding of the topic and the data. We had regular regional virtual meetings and the team was great and active,” Díaz-Struck explained.

The teamwork also extended to the country level. For example, three media organizations worked together in Mexico, three in Argentina and two in Brazil.

In Mexico, the 12-person team was comprised of reporters from Mexicanos Contra la Corrupción (MCCI), Quinto Elemento Lab and the magazine Proceso.

“When we learned the investigative topic for this year, reporting first was done about Mexico’s situation with respect to the topic of regulation and monitoring of medical devices, and from that we had at least two meetings with all the members of the Mexico team to design the entire battery of information requests we made,” said Thelma Gómez, journalist with MCCI.

They divided the work of requesting information, and then gathered and systematized the answers. The team held meetings to check progress and decide which stories to follow, she added. Working in a group, the reporters were able to move reporting along more quickly, Gómez explained.

In Argentina, the collaboration was an effort of six journalists from La Nación, Infobae and Perfil.

“We had worked together on the Panama Papers and on the Paradise Papers, so we had the dynamics, we knew each other and knew how to organize tasks. The results that this team achieved, in all projects, rest in the trust and mutual respect that we have with each other,” said Argentine journalist Sandra Crucianelli, who worked for Perfil.

As far as communication, journalists from around the world took advantage of a tool used in previous ICIJ transnational collaborations: Global I-Hub.

“It’s a kind of closed Facebook, where you can follow themes of interest (in this case, a product or a company in particular, a country, etc.). You can exchange information, ask questions and it transforms into a kind of collective reporting,” Francisca Skoknic, a reporter from Chilean media partner LaBot, explained to the Knight Center.

Latin American reporters also met with each other and Díaz-Struck via teleconference to talk about the project and to share progress in the final stages, Skoknic said. And in the days leading up to the launch of the reports, Spanish-speaking partners were very active in the I-Hub and in messaging, she added.

“There, we coordinated the last details and solved doubts. There was a lot of generosity and team spirit, although many of us don’t know each other. Those who did translations shared them with the rest, as well as visualizations and graphic pieces."

But before all the reporting and the publication of results, the first challenge was finding the data: the Implant Files team sent more than 1,500 requests for information.

“It’s not a project where we had all the documents or all the data in one place, but we had to harvest them,” Díaz-Struck explained.

Media outlets shared documents obtained through these information requests through the ICIJ Knowledge Center, as explained by Díaz-Struck. The platform was previously used for the consortium’s Paradise Papers investigation.

Mexico, one of the largest markets for medical devices in Latin America, is illustrative of a challenge in accessing data: low returns. Journalists filed more than 900 requests in the country and received only 40 answers, according to Díaz-Struck.

Among the information requests made by Implant Files partners was data about recalls, which would inform a good deal of the reporting done by media partners.

According to ICIJ, “fewer than 20 percent of the countries in the world had public data online permitting citizens to find safety and recall information on medical devices.” Further, Díaz-Struck added that the level of detail in the information coming from different countries is not always uniform, posing another challenge.

Some of the information received from information requests went into the International Medical Devices Database (IMDD), a searchable database of more than 70,000 recalls, safety alerts and field safety notices that has been published by the ICIJ.

The records in the IMDD are from 11 countries, including Peru and Mexico. Díaz-Struck said records from more Latin American countries, including Brazil, will be added to the IMDD in coming updates.

As part of the investigation, reporters –including those in Peru and Argentina– were able to trace items recalled in the U.S. to their own countries.

“Latin America is very opaque about how imports, purchases of these devices and the relationship of doctors with medical implant manufacturers are handled. Patients are very poorly informed by their doctors about what is placed in their bodies,” Fabiola Torres, Peruvian journalist from Ojo Público and ICFJ Knight Fellow for Latin America, told the Knight Center.

“Therefore, we decided to keep track of where the majority of implants in Peru come from, because it is so easy for products that have been retired or have received alerts in the U.S. or Europe to enter,” said Torres, who collaborated on the investigation through her project Salud con Lupa.

Through information requests, discoveries about regulation, or lack thereof, were made in Chile.

“In Chile, except for five exceptions, medical devices are not regulated, so, on the one hand, we concentrated on showing this weakness in Chilean legislation,” said Andrea Insunza, a reporter on the team from LaBot. “Using the Transparency Law, we requested information about the ‘incidents’ or adverse ‘events’ caused by devices and the public body in charge of the subject reported only four cases for 10 years. This surprised the ICIJ team: Chile became an example of lack of regulation.”

The ICIJ team itself also faced a challenge when it came to analyzing the data, for which they employed machine learning to uncover under-reported deaths, Díaz-Struck explained.

Rigoberto Carvajal, a Costa Rican journalist on the ICIJ data and research team, created algorithms to analyze records in the U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s Manufacturer and User Facility Device Experience database, or MAUDE. The database contains medical device reports of “suspected device-associated deaths, serious injuries and malfunctions,” according to the FDA’s site.

Carvajal’s algorithm analyzed reports for mentions of deaths that were misclassified and then a team of eleven people manually combed the records to make sure the results were accurate. Carvajal ran his algorithm again to see if a medical device was involved in the death and the team again checked the flagged records, one by one.

“ICIJ found 2,100 cases where people died, but their deaths were classified as malfunctions or injuries,” the consortium reported. “Of these, 220 reports showed that devices may have caused or contributed to the deaths. The other reports did not include enough information to determine conclusively if the device played a role in the patients’ deaths.”

In addition to reporting on the lack of public information available regarding medical devices, the lack of regulation, and under-reported deaths, Latin American journalists also looked at conflicts of interest between doctors and the medical device industry.

Others took deep dives into some of the giants of the industry, like Medtronic in Chile, and their roles in the region. News organization piauí looked at the growth of lawsuits against Silimed, a breast implant manufacturer in Brazil, where more than 215,000 aesthetic surgeries to implant silicone prosthesis were done last year.

Media partners also interviewed patients, the people affected by malfunctioning or unsuccessful devices or implants. Agência Pública in Brazil interviewed women who experienced serious negative side effects from the female sterilization device Essure.

El Universo interviewed the executive president of the Ecuadorian Association of Producers and Distributors of Medical Products (Asedim) who denounced the presence of fake products and contraband in the national public health system.

These stories are being shared across borders, with media partners publishing each other’s findings and translating them into other languages.

To get the reports to the widest audience possible, Latin American outlets are utilizing a variety of storytelling formats.

For example, Torres said this project was the first time Ojo Público in Peru used 3D visualizations and posters “in the style of El Surtidor [from Paraguay]” to summarize findings. Using animation and textual explainers, the posters answer questions like “How does a defective implant get into your body?”

Media partners are sharing findings via video as well. For example, MCCI in Mexico employed video to share trial documents used in their reporting on a subsidiary of Zimmer Biomet, a manufacturer of dental devices, that was investigated by U.S. authorities, according to MCCI. The use of video on social networks has great effect, as pointed out by Raúl Olmos, author of the report.

In Chile, a chatbot was employed to tell readers about insulin pumps and sanitary control of medical devices in the country, among other stories. When LaBot releases a new report as part of the investigations, readers get notifications on Facebook Messenger or Telegram and can then converse with the chatbot to learn more.

“It is a new way of telling stories and we believe that it contributes something different to the project. The first chat we launched was the main report of ICIJ, which is very long and gives a lot of information,” said Andrea Insunza, a reporter on the team. “The appeal of the robot is that it was able to take that data and relate it in a simple and friendly way, simulating a conversation with our audience.”

Now, some media partners are looking to the audience to gather information for future reporting. They’ve used social media to put out calls to patients, medical providers or others involved in the medical device industry, to share their stories.

“We want to follow up on this issue,” said Gómez, from MCCI. “So the information that readers can give us in the coming months will be very valuable.”

Below are the Latin American media organizations that participated in The Implant Files and links to their investigations:

Media: La Nación, Perfil, Infobae

Reporters (6): Emilia Delfino, Iván Ruíz, Maia Jastreblansky, Mariel Fitz Patrick, Ricardo Brom, Sandra Crucianelli

Reporters (8): Allan de Abreu, Anna Beatriz Anjos, Bernardo Esteves, Camila Zarur, Gabriele Roza, Jose Roberto Toledo, Natalia Viana, Vitor Hugo Brandalise

Media: LaBot

Reporters (4): Andrea Insunza, Francisca Skoknic, Ignacia Velasco, Paula Molina

Reporters (1): Rigoberto Carvajal (data and research team, ICIJ)

Media: El Universo

Reporters (1): Mónica Almeida

Media: Mexicanos Contra la Corrupción, Proceso, Quinto Elemento Lab

Reporters (12): Andrea Cardenas, Daniel Lizárraga, Dulce González, Ignacio Rodriguez Reyna, Jorge Carrasco, Laura Sánchez Ley, Mathieu Touliere, Miriam Castillo, Raúl Olmos, Thelma Gómez, Valeria Durán, Xanic von Bertrab

Media: Ojo Público

Reporters (6): Antonio Cucho Gamboa (web developer, ICIJ), Fabiola Torres, Jason Martinez, José Luis Huacles, Mayté Ciriaco y Rocío Romero

Reporters (1): Emilia Díaz-Struck (data editor, ICIJ)

*This post was updated to clarify that the Knowledge Center was used in the Paradise Papers, not the Panama Papers.