A week ago, a police action resulted in 23 deaths in Vila Cruzeiro, a favela or slum in the North Zone of Rio. The scene and violence changed little 20 years after the death of Brazilian journalist Tim Lopes. It was in Vila Cruzeiro where he was captured, tortured and assassinated when he was investigating for TV Globo a complaint of sexual exploitation of minors by drug traffickers. On the anniversary of the journalist's execution, LatAm Journalism Review (LJR) heard from friends, work colleagues and relatives of Lopes, who became a symbol of violence against the press in Brazil.

"We can say that there was a before and an after in journalism, and the landmark is the death of Tim Lopes. A brutal death, that murder," Angelina Nunes said. She is the coordinator of the Tim Lopes Program, which investigates cases of violence against journalists in Brazil. "We started to discuss the need for bulletproof vests, helmets, armored cars. Whether it’s worth putting a team in that place in the middle of a shooting or not. This type of reflection inside the newsroom did not exist before. We in the press placed ourselves as the fourth estate, and we believed there was a certain respect for us when we entered places.”

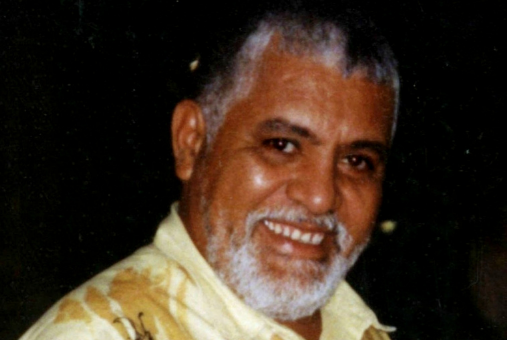

Tim Lopes was an experienced journalist in undercover situations and the use of hidden micro-cameras. (Photo: Courtesy)

With 25 years of covering public safety in Rio de Janeiro, independent investigative journalist Sergio Ramalho experienced firsthand the changes that took place in newsrooms after Lopes' murder. He himself has taken three safety courses throughout his career, as stipulated by the newsrooms where he worked, to be better prepared for potentially violent situations. This type of concern with training professionals to deal with risky situations has become a routine part of newsrooms in the years since the journalist's death.

"We were reporting in several at-risk places and we really didn't have a notion of what the impact could be. The media started to prepare their professionals who were going to the front. What we experience in Rio de Janeiro is not very different from a conventional war, especially when you do the kind of reporting that he did, in conflict areas, and using a micro-camera," Ramalho said.

Another effect of the security measures implemented after Lopes' death was that access to favelas by Carioca journalists [born in Rio de Janeiro] became limited. Previously, it had been common for journalists to enter favelas dominated by drug gangs even while unescorted by the police. Many media companies established rules that ended up blocking their teams’ access to areas at risk of armed confrontation. The preference became to do coverage in the outskirts, with a detrimental effect on the quality of information.

"I was born and raised in Rocinha [a notorious favela for being huge, violent and located in the middle of one of Rio’s most affluent neighborhoods]. As a journalist, it was easy for me to deal with risky situations in areas of conflict -- I was more than used to protecting myself from the countless confrontations I had witnessed since forever. But after that June 2, 2002, entering a favela as a reporter was only possible with the police by my side. It changed everything," Che Oliveira, veteran TV reporter and winner of the 2008 Tim Lopes Investigative Journalism Award, said. "[Afterwards,] there was no longer any way to ascertain whether a death inside a favela had really been the result of a confrontation or an execution perpetrated by security forces."

One of the main legacies of Tim Lopes' death is the creation, in December 2002, of the Brazilian Association of Investigative Journalism (Abraji, by its Portuguese acronym), which has become one of the most influential journalist associations in the country. At its genesis were the commotion in the profession and the discussions about journalists' safety that followed the murder. The kick-off was the seminar 'Investigative Journalism: Ethics, Techniques and Dangers,' organized by the Knight Center for Journalism in the Americas.

A founding member and the first president of Abraji, journalist Marcelo Beraba believes that despite everything that has changed in security protocols for journalists, the situation today is even worse than it was 20 years ago. This is especially so considering the increased threats and the efforts to discredit journalists by politicians and other people in positions of power.

"Today we have more technological and digital resources at the service of investigative reporting, but working conditions are more difficult. The financial situation of news companies and journalist collectives has worsened with the epidemic and endless economic crises. Journalists are working more and earning less. And we all suffer from the Bolsonaro government's violent, daily attacks against democratic institutions, the press as one of the main targets. Tim would never accept this situation, just as we journalists do not accept it and we resist," Beraba said.

In the same vein, Nunes is concerned about the precarious working conditions, the unreliable work contracts, and the lack of legal support to deal with the frequent lawsuits and cases of judicial harassment to which investigative journalists are subjected.

"There is a whole movement to discredit journalism and journalists. Especially so when you have, in charge of the country, a person who stands up against journalism, spreads rumors, and encourages this. This is very bad for democracy and for all of us. Quality journalism is necessary, resistance is necessary. It's what I always say: journalism is resistance," Nunes said.

In the assessment of the president of the National Federation of Journalists (Fenaj), Maria José Braga, in the 20 years since the death of Tim Lopes, "violence against journalists has worsened and diversified, as absurd as it may seem."

"We are still awaiting, from the National Congress, the approval of a bill that federalizes the investigations of crimes against journalists and other measures, such as institutional positions against violence against journalists. From the Executive, we are waiting for the creation and implementation of protocols for the actions of the security forces, especially for actions in public demonstrations and conflict situations. From the Judiciary, we are always demanding speedy trials for aggressors and the non-use of lawsuits to intimidate journalists," Braga said.

The president of Fenaj recalls that despite the protection measures implemented by news companies soon after Lopes' death, there is no unified and mandatory national protocol with effective measures to ensure the physical and mental integrity of journalists in cases of violence.

After the death of Tim Lopes, journalism in Rio de Janeiro would suffer two more hard blows. In 2008, a team from the newspaper O Dia was doing an undercover investigation in a slum about the buying of votes by criminal groups formed by police officers and former police officers: the militias. A reporter, a photographer and the drivers were barbarously tortured, but survived. In 2011, cameraman Gelson Domingos died while covering a police action in another slum: the bulletproof vest he was wearing did not resist the rifle shot.

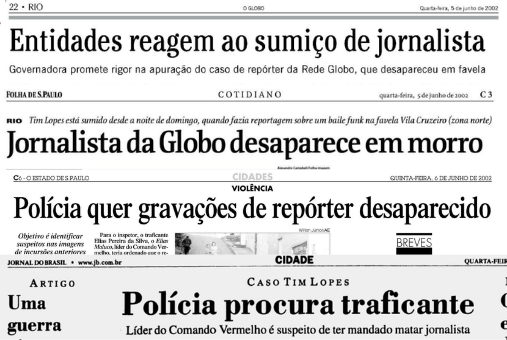

The journalist's disappearance and death were widely covered at the time and the case became a watershed in Brazilian journalism. (Credit: O Globo, Folha, Estadão and Jornal do Brasil)

Lopes was murdered ten months after producing a feature story that showed the open sale of drugs in broad daylight in another Rio favela, Grota, next to Vila Cruzeiro where he would be captured. The story earned him in 2001 the Esso Journalism Award, the most traditional and prestigious award in the Brazilian press. On the occasion, he made use of two resources characteristic of his work: the infiltration and the use of a hidden micro-camera.

"He had the quirk of really trying to experience the lives of the characters in his stories, taking part in the daily life of the people he portrayed. This created almost a school, this thing of pretending to be a beggar to register the drama of the street kids in downtown Rio. Or being a coconut water seller at the Central [train station] to register the daily violence of robberies. This is something he did on a daily basis and he was a master," said Alexandre Medeiros, a board member of the Brazilian Press Association (ABI) and a close friend of Lopes. Medeiros’ daughter, Cecília, is Lopes’ goddaughter, who christened her a week before he disappeared.

"Tim was very important to us in journalism, in Rio de Janeiro and in Brazil. He made use of the micro-camera when this model of capturing images was beginning here in Brazil. The news outlets had a certain resistance to it, just as in the past there was also resistance to changing from typewriter to computer. And Tim used the micro-camera very well," Ramalho said.

Ten days went by from his disappearance on June 2, 2002, until the charred fragments of his body were found. Then, the hunt for the journalist's executioners took another four months until the arrest of the gang's leader, Elias Pereira da Silva, known as “Crazy Elias.” He was convicted of the crime and died in prison in 2020.

"Tim Lopes was a journalist ahead of his time. While today, society in general is debating ways to increase diversity in news companies and is concerned with issues of social relevance, Tim was already doing this 25, 35 years ago. Journalists like him come about rarely. I'm very proud to have spent time with him," Marcelo Moreira, journalism director of Globo Minas and former president of Abraji, said.

"Tim was an affectionate and caring son and brother to all his family, parents and siblings! He took the pen and a tape recorder, and followed his instinct, permeated by indignation and the strength of his well-chosen profession. He developed his work focused on fighting discrimination and social injustice," Tania Lopes, the journalist's sister, said. "Today, with the oppressive political context, which omits and excludes, Tim's presence, his work, is necessary. Many journalists follow in his footsteps in the country. And that’s a good thing!"

*Cover photo: Tomaz Silva/Agência Brasil