"The situation is a very unsettling crisis in which several elements dovetail," said Carlos Martínez de la Serna, program director of the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ). He explained the environment in which journalists, the media and freedom of expression in general find themselves in Ecuador and which is described in the recent CPJ report "Ecuador on edge: Political paralysis and spiking crime pose new threats to press freedom."

The report, published on Wednesday, June 28 and written by Carlos Lauría, analyzes what is causing the increased risks for journalists in the practice of their work, the effects this has on their daily practice, and ends with recommendations to national authorities and the international community.

"For us there are two central [elements]: A security crisis that exposes journalists to violences, and I say violences in the plural because there are different forms and origins of this violence. [...] And on the other hand, this situation takes place at a time of political uncertainty in which it’s very important that the different institutions and political parties, who understand their different visions for Ecuador, coincide in identifying this problem and the solutions to solve it," Martínez de la Serna told LatAm Journalism Review (LJR).

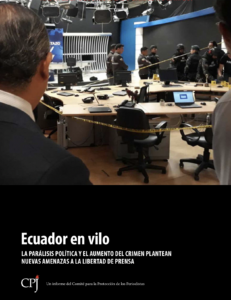

Cover of the CPJ report on the situation of press freedom in Ecuador. The photo shows journalist and news presenter for national television network Ecuavisa, Lenín Artieda, watching Ecuadorian authorities enter his newsroom to investigate a letter bomb sent to him. (Photo: Attorney General's Office of Ecuador)

According to Martínez de la Serna, journalists in Ecuador are facing "[types of] violence" from organized crime, verbal violence — through aggressive rhetoric usually from authorities —, as well as violence during coverage of protests or public events, and even threats for covering more sensitive topics.

The figures indeed show that it is becoming increasingly difficult to practice journalism in the country. During 2023, the country has registered the exile of at least two journalists, the sending of explosive material to news outlets and reporters, and 96 attacks on the press in the first four months of the year.

A trend that is not new: In 2022, the NGO Fundamedios, recorded 356 attacks on the press, the highest figure since 2018. That same year, there were three murders of journalists. However, CPJ has been unable to confirm whether the three killings were related to the journalist’s work, “but the deaths inevitably have had a chilling effect on their colleagues.”

In addition, an economic crisis has been exacerbated by the COVID pandemic, which has led to 22,948 layoffs in media companies from March 2020 to November 2021.

The legacy of former president Rafael Correa, who was known for his conflictive relationship with the press, is also still present in the country. According to the CPJ report, on the one hand, his actions such as filing defamation lawsuits, enacting restrictive measures, and denigrating critics "have weakened the media's ability to report the news," local journalists told CPJ. On the other hand, online defamation campaigns and troll warfare by former President Correa continue to undermine private news outlets whose finances have been affected.

All this in the midst of a political crisis after President Guillermo Lasso dissolved the National Assembly while it was impeaching Lasso. For journalists and activists, this is creating the "perfect storm" regarding press freedom, according to CPJ.

The increase in crime in general in the country has had a direct effect on the practice of journalism. According to the report, violence and organized crime has left "silenced zones" in the country.

After examining conditions in 10 provinces — Carchi, Chimborazo, Cotopaxi, Esmeraldas, Guayas, Loja, Los Ríos, Manabí, Pichincha and Santo Domingo de los Tsáchilas — CPJ found that "organized crime and local political forces have endangered the media in much of Ecuador, taking advantage of their vulnerability, precarious working conditions and lack of security."

In Esmeraldas, for example, the place where a team from the newspaper El Comercio was kidnapped and murdered by dissident members of the Colombian FARC guerrilla, journalists have decided to "turn a blind eye." According to information provided to CPJ by the Fundación Periodistas sin Cadenas, journalists in the area avoid reporting on any criminal activity.

Added to this are complaints from some journalists and press freedom advocates about the lack of "rigorous investigations" in cases of crimes against journalists and news outlets. The country's Attorney General told CPJ that the security crisis is "unprecedented" and that the protection of victims and witnesses requires greater resources. Regarding the investigation of cases, she said that all these cases needed time and added that some journalists would not collaborate with the investigations.

Given this scenario, CPJ has stated that one of the urgent actions by the government is an injection of resources for both the Protection Mechanism and the Prosecutor's Office. For Martínez de la Serna, although the mechanism exists and the office is "very capable" in compiling statistics on the situation, it requires more money to be able to execute specific protection measures or when they [journalists] need to be relocated, among others.

"There is a mechanism, which is already a step. But if the mechanism does not have critical financial resources, it’s not going to be possible, it’s not going to be able to respond to a threat like the one that exists right now in Ecuadorian society already. That has been clearly demonstrated, it’s not a projection for the future," Martínez de la Serna said.

Another issue that CPJ considers vital and that was recommended to the authorities in the report is the regulation of the Organic Law of Communication (LOC, by its Spanish acronym). The former LOC, enacted by former President Correa and known as the "gag law," left a legacy of millions of dollars in fines for media and journalists, the institutionalization of repressive mechanisms, and state regulation of editorial content, CPJ said.

In November 2022, President Guillermo Lasso signed a new law that corrects some of the most important issues: State power over the media, guaranteeing freedom of expression in social media and the protection of journalists, according to the CPJ report.

However, for Martínez de la Serna its regulation is necessary and urgent. "It is essential, at least in one critical aspect, which is to limit, we say it in the report, state interference in the media and at the same time regulates the protection of journalists, thus addressing essential elements such as freedom of publication, the right to journalistic activity without interference, and the element of security that is central to our report," he said.

Press conference in Quito, Ecuador, during the launch of the report "Ecuador on edge" on June 28th. From left to right: Carlos Martínez de la Serna, program director of CPJ; Carlos Lauría, senior consultant for CPJ; and César Ricaurte, executive director of Fundamedios. (Photo: Courtesy Fundamedios)

The report also analyzes the situation in the country and its relationship with the international community. For journalists and other sources who spoke to CPJ, there is a need for greater attention from the international community to what is happening in Ecuador. Despite the fact that the country has become “a key puzzle piece for organized crime,” the country's experience “is usually eclipsed by countries with heavier regional political weight,” according to the report.

In addition to the fact that Ecuador's press freedom crisis should receive support from organizations such as UNESCO, the OAS and the European Union, CPJ also recommends in its report that the work of Ecuadorian journalists be publicly supported, and recommends an official visit by the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights.

The report ends with a series of recommendations to the executive branch, as well as to judicial, administrative and law enforcement authorities. Martínez de la Serna highlights, however, three aspects that should be resolved as soon as possible.

"Three aspects that should happen now, that should happen in the next few weeks and if it is days, all the better: The allocation of a direct budget and that of extraordinary resources for the development of the protection mechanism, the allocation of resources to the Prosecutor's Office, and the regulation of the [organic communication] law. These three things are urgent," Martínez de la Serna said forcefully.