Drawing is capable of conveying the atmosphere of a moment, recreating a scene in the past, and expressing sensations and thoughts inside a person's head.

All of this can make it a tool at the service of journalism: drawn or painted images can sometimes summarize in clear and expressive ways aspects of reality that text, photography, video, infographics and sound alone may have difficulty translating.

Although comics have long been considered a mature form of art, using them to produce journalistic work is still in the minority compared to other formats.

A newly released book in Brazil aims to change this situation. It explains, step by step, how to produce comics journalism, from defining the story, to the investigation, to the scripting and editing.

Available since the end of last year, launched at the Congress of the Brazilian Association of Investigative Journalism (Abraji) in July and about to be published in Germany, the "Pequeno manual da reportagem em quadrinhos" (Small manual of comics journalism), by Porto Alegre journalist and researcher Augusto Paim, shares recommendations and best practices for anyone who wants to produce comics journalism, whether they are journalists, artists or aspire to be both. The manual is a result of his doctorate from Bauhaus University in Germany.

Book cover of the "Pequeno Manual da Reportagem em Quadrinhos", written by Augusto Paim, that offers step-by-step guidance on how to create comics journalism

"Comics are an artistic language that can be used for anything,” Paim, who creates comics journalism himself, told LatAm Journalism Review (LJR). “Including superhero stories and children's books. But there is also a lot that goes beyond that."

For Paim, comics journalism should not be seen just as a way of simplifying information, but as an area of journalism, just like print or television journalism.

This area of journalism includes different modalities, including the production of features, news, interviews or reviews. The author focuses specifically on the first type, although some of his tips also apply to other forms.

Among the Brazilian journalists working in the format, Paim highlights Pablito Aguiar, known for embracing the comic interview format, and Carol Ito, who did an important report on women in an open-air drug market in São Paulo for piauí magazine, in addition to mentioning Gabriela Güllich and Cecilia Marins as other important figures in the area.

In search of practical tips and reflections for those who want to produce comics journalism, LJR spoke to Paim and came up with seven recommendations.

1) There are topics that are more and less conducive to comics journalism

In the book, Paim proposes a maxim: "this should be our goal: to make comics journalism that simply wouldn't work in other formats. That needs to be made in comics!”

This, says the author, means that there are stories that are more or less favorable to the comic book format. Some things work in comics, and wouldn't work in other languages.

"The language of comics allows for an artistic and narrative depth that can be difficult in other formats,” Paim said. “This may have to do with making a theme more accessible, but also with the possibility of deepening themes artistically and creating an atmosphere for work that would otherwise be more difficult."

Paim said comics journalism allows for a more subjective and personal approach to reporting. Comics can be especially useful for dealing with sensitive topics or situations where the privacy of sources needs to be protected.

“Sometimes, the life of the person speaking is at risk or they are a victim of domestic violence. In these cases, you can draw people protecting their identity,” he said.

2) The style of the stroke impacts the narrative

Paim mentioned that the drawing style directly impacts the journalistic narrative. The sophistication of the stroke, therefore, maintains an intimate relationship with the journalistic content.

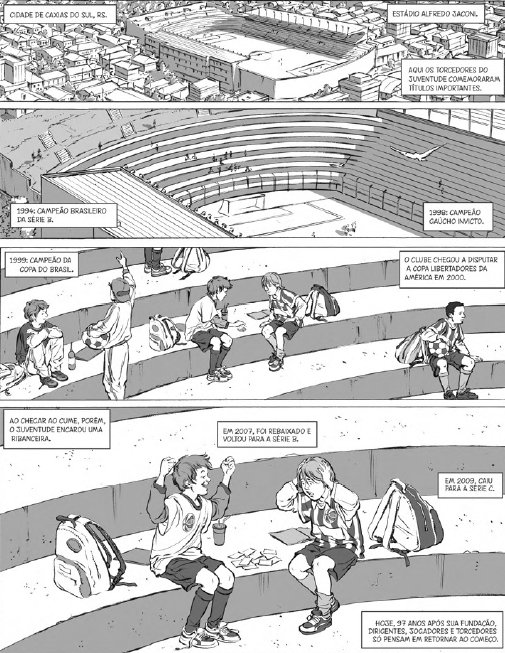

A page from 'Juventude: Tempo de crescer' (2010), written by Augusto Paim and illustrated by Ana Luiza Koehler, published by Continuum magazine (Image: Courtesy)

He said a simplified stroke, for example, can be useful for news.

"A drawing with a few strokes is easier to complete and could be used, for example, to make news in comics. Newsrooms have illustrators who create illustrations to complete content on the same day, so why not make news in comics?”, Paim said. “News is about communicating in a simple way.”

In contrast, a feature may require other techniques, such as watercolor, engraving or colored pencil.

3) Collaboration between journalists and artists in the investigation

Paim said that the presence of the artist during the journalistic investigation is essential. It allows the illustrator to understand first-hand what the environment to be portrayed and what the characters are like.

“Otherwise, the person will receive a ready-made feature and will just illustrate it. And then it’s an illustrated feature, and it’s not comics journalism,” he said.

Paim said the artist assumes a role similar to that of a photographer who collects images and notices visual aspects while the reporter mainly takes care of interviews.

“The genre lives from this encounter with reality, from going to the streets, from talking to people”, he said. “If you have two people involved in the work, why should only one of them be present?”

In the book, he describes how using a sketchpad can open doors: often, upon noticing that someone is drawing, potential sources approach and contacts are made that might be difficult for a conventional reporter to get.

Paim also adds one point: if it is not possible to be present at the location of the events, there must at least be a visual survey to ensure that the design matches reality.

4) There are disadvantages to the format

Paim lists some disadvantages of comics journalism. The first is the production time, which takes longer than a feature made up of text with photographs.

“If you want to do comics journalism, you need more time, and as a result, some issues may become outdated,” Paim said.

He said this delay leads renowned authors, such as Maltese-American cartoonist and journalist Joe Sacco, to address “conflicts that have long since lost media attention.”

Another disadvantage is the fact that comics rely heavily on scenes. To narrate a scene without much text, however, many pages are needed, which involves more design and production time.

“This can make it difficult to create a well-done comic story in a short format,” Paim said.

He said an alternative would be a hybrid format. That is, not all work needs to be in comics format, it is possible to insert text passages in the middle, before or after the work.

Another disadvantage, finally, is the fact that comics are still often associated with simple language, such as easy reading. Many associate comics with something childish, which disregards the fact that, in many cultures, such as in France and Belgium, comics are consumed by adults as literature or journalism.

“In Brazil, although there is an immense production of comics on various topics, this limited vision still persists, which hinders the function of comics journalism, which is seen only as a way of simplifying themes,” Paim said.

5) Collaboration is not free from conflict

In the book, among the personal experiences that Paim shares, there are cases in which the lack of harmony between the reporter and the artist hampered the fluidity of the work.

Paim said that conflicts with artists during the production process generally arise due to differences in work routines and ways of thinking.

“Sometimes there is a conflict because artists generally work more alone, and the reporter is used to going out into the field,” Paim said.

He also mentioned that these conflicts, although challenging, can be healthy and contribute to the creative process.

“It is normal for impasses to occur, especially when there are different ideas for the work,” he said.

Paim said the process of creating comics journalism can be a learning experience for artists about journalistic practices.

“The investigation ends up almost becoming a journalism course for those who are drawing,” he said.

6) Ethical obligations are the same as those of traditional journalism

The ethical and deontological obligations of comics journalism are the same as those of traditional journalism, Paim said.

He explained that although drawing offers greater flexibility to represent complex situations, the work needs to be anchored in investigation and reality, avoiding any type of exaggerated fantasy that compromises the veracity of the facts.

Paim added that drawing can, in some cases, facilitate ethical decisions, as it allows more reflection before representing a situation visually, unlike photography, which captures the moment instantly.

The versatility of the language also makes it possible to represent different perspectives, which favors translating complex situations in a nuanced way.

He gave the example of how, when covering protests, photography can capture isolated moments that can generate skewed interpretations, while drawing allows the scene to be recorded in a more contextualized and balanced way.

“A photograph can be decisive in characterizing a person as an aggressor or being attacked. You see a police officer with his baton raised hitting a student, and in the next image the student fights back,” he said. “Depending on the photo, you can characterize one as an aggressor and another as a victim. In drawing, you have the possibility of recording these contradictions in a single scene.”

7) Common mistakes: redundancy and limited use of narrative possibilities

Some common errors in comics journalism include a redundancy between text and image, the excessive presence of texts and the limited use of the narrative possibilities of comics.

A page from "In Front of the Bars", written by Augusto Paim, illustrated by Bea Davies, published by was wäre wenn in 2019 (Image: Courtesy)

Comics journalists must understand that it is a hybrid format, in which the image and text dialogue with each other, each with its own contribution, Paim said.

“For the text to say something that the image already shows or for the image to repeat a text is a very poor use of the possibilities of comics journalism,” he said.

Comics journalism offers the possibility of creating parallel narratives between text and image, and this can give rise to different meanings, which cannot be reduced to one or the other.

“When the text shows one thing, and the image shows another, from this discrepancy, you create other meanings,” Paim said.