This article was originally published by FOPEA and is republished here with permission.

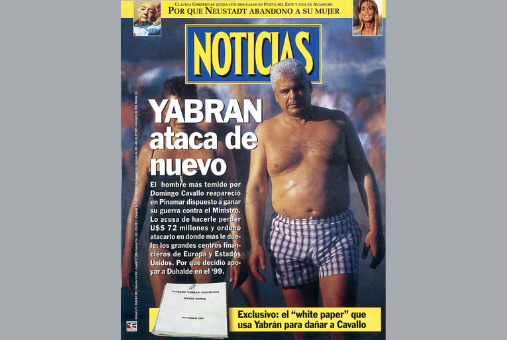

[LJR Note] Argentine journalist José Luis Cabezas was one of the first to photograph businessman Alfredo Yabrán, a well-known and reclusive businessman with alleged connections to corruption and organized crime cases. The photographs, published in March 1996 in the Noticias magazine, were identified as the reason behind his murder on Jan. 25, 1997. According to the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ), Argentine courts convicted eight people of the kidnapping and death of Cabezas. “The court found that the murder had been planned by Yabrán, who committed suicide in 1998,” CPJ reported. Twenty-five years after the crime, none of those convicted by the Judiciary remain in prison, according to Infobae.

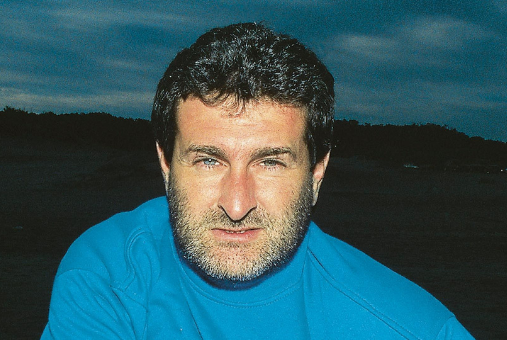

On Jan, 25, 1997, photojournalist José Luis Cabezas was kidnapped, beaten, murdered, and cremated in a vacant lot on the Atlantic coast. On the 25th anniversary of this crime, the Argentine Journalism Forum (FOPEA, by its Spanish acronym), invited 25 journalists to remember him with anecdotes and reflections on what his death represents to Argentine journalism.

1) Gabriel Michi, friend and coverage partner

25 years since that 25. A quarter of a century since that sinister day in January 1997 when our history changed forever. That of my colleague and friend José Luis Cabezas, my partner-in-crime in so many journalistic “adventures.” That of his shattered family. That of his devastated colleagues. That of all journalism in shock. That of a shaken society. That of a battered country.

25 years in which the worst attack on Freedom of Expression took place in Argentina since the return of democracy. An attack meant to silence, but which obtained the exact opposite. It became a deafening cry against barbarism, against injustice, against corruption, against the mafias.

Those mafias that sought to continue building power with impunity. But they could not. Because, José Luis, the same one they tried to eliminate, was more present than ever. In each of his committed colleagues, in each good citizen, in the painful and justice-demanding gaze of his family. We all were, are and will be José Luis Cabezas. Because his absence hurts and moves us to tears. But they, his murderers, are weighed down by his presence. Cabezas, present! Now and always!

2) Alejandra Daiha, director of the Noticias magazine

It was strange for those of us in the newsroom with him, to accept that José Luis, that funny, bastard, a great father and determined to be a great photographer, became a banner. That black and white portrait of him that went around the world should have been nothing more than a passport photo, but instead it became a flag and froze it in time. For the rest of us, who were able to grow old, his crime left us with the sadness of knowing that journalism can also be paid for with life in a democracy. Cabezas was not a kamikaze. He must have turned 60 a few months ago. I imagine him the same. Climbing on tables, chairs and stairs to achieve those photos from above that were his hallmark. We don't forget you, "chabón".

3) Pablo Sirvén, current editorial secretary of the newspaper La Nación; at that time, general editor of the magazine Noticias

Charcoal bag on top of empty fruit crate. This is how José Luis Cabezas taught me how to make barbecues in one of the two summers that we shared a season in Pinamar making notes for the magazine Noticias. He sang "Give me a lemon" loudly, by Divided, which he played all the time in the car in which we moved between forests and seas.

Funny, protesting, hyper-professional, he looked for the best light in the first and last sun of the day to achieve his incredible photos. He was aware of the dangers he was exposing himself to, but his clicking finger always got the better of him.

4) Jorge Fontevecchia, President and CEO of the Profile Group

In the rest of Latin America, the murder of journalists is a practice that has not yet been banished. The reaction of Argentine society to the death of José Luis Cabezas taught the barbarians that murdering a journalist ended up having worse consequences for themselves. The impunity that is still maintained in other crimes, became impossible in the murder of a journalist due to the enormous visibility that the act would have. José Luis Cabezas with his life except that of many journalists during the last quarter century. And he will continue to do so.

5) Paula Moreno Roman, president of FOPEA

A year after the death of José Luis Cabezas, the city of Esquel inaugurated one of the first sculptures that the country had, honoring our dear colleague and calling for the search for truth and justice.

Gabriel Michi, María Cristina Robledo and Daniel Das Neves (UTPBA) shared a moving moment of unity around that monument located in front of the Esquel Courts building with José Luis's eyes carved into the stone and his deep gaze fixed on the symbol of justice.

Cabezas is not, was and will not be “a case”. It is the constant fight against oblivion and impunity that has managed to unite the journalistic community in Argentina. From this corner of the country, every January 25, they shout “Cabezas, Presente” again.

The photo that took José Luis Cabezas’ life: Alfredo Yabrán’s face. (Credit: reproduction)

6) Edi Zunino, who led the Noticias team magazine that investigated the homicide

I always resisted converting José Luis Cabezas into a flag. First, because he was a common man. Second, because he was a colleague with whom it was worth spending hours and hours of creativity (my most unforgettable work trips abroad happened when I was “paired up” with him). And, third, perhaps, for assuming that transferring him to the realm of the symbolic would take away substance to my own life. Of course, 25 years after we were thirty-somethings, one has lived long enough to look back and evaluate one’s life. Mine lies with the Malvinas War (Falklands War), the recovery of democracy and the homicide of Cabezas. I’m still not quite sure what this all means, but that’s what I’m made of, and to a great extent, that’s who I am. Cabezas has to do with my way of understanding Argentina and journalism. Everyday. Without fail. It’s a survival mark. The flash effect of a lighthouse. A moral tattoo.

7) Guillermo Cantón, friend and co-worker

Dear José Luis: It seems that there are many people who want to know about you, I would tell you that everyone asks me. I know it wouldn’t bother you, because we trust each other and, let's face it, you love it. Today, to make you feel proud, everyone talks about you. I tell them that you were good to your children, bad with the bad ones, irreplaceable with Cristina, naive with your eyes, frank with laughter, tireless with the camera, transparent at heart, curious by trade, a very broad friend and brotherly with me. For the forgetful ones, we wear a black ribbon in your memory. I am not in mourning. I've got a spare laugh from you. Thanks for everything and until next time.

8) Norma Morandini, journalist and writer. At the time, she was a correspondent for the Spanish magazine Cambio 16 and the Brazilian newspaper O'Globo.

The day Jose Luis Cabezas was murdered, a Brazilian friend, Claudia Merian, married to the then Cultural Attaché of the French Embassy, who was the one who introduced José Luis as a photographer for the embassy, called to tell me that the photograph in which we appear together, was aken by Cabezas. I went to look for the photograph, and I was shocked because the glass in the picture frame was broken in half. So I left it. I keep the photo in a visible place and every time I look at it, I remember José Luis.

9) Santo Biasatti, NET TV journalist

Don't forget Jose Luis Cabezas. Against impunity always. The best tribute we can pay him is to firmly uphold the principle of demanding justice. We will not forget his assassins. Some live among us. We do not forget those who remained silent nor those who refused to give all their support to the family. To remember is not a crime. To hide it was and is a miserable thing.

10) Italo Pisani, managing editor of Diario Río Negro

The antibodies left in all of us by the forceful social reaction to the brutal crime of José Luis Cabezas 25 years ago cannot — should not — have an expiration date. This tragedy took a turn in our history: it unmasked the mafias of power, the despicable police, and impunity. It also closed ranks between press workers and placed value on professional journalism that seeks the truth at any cost. Let's never lower the flag inspired by the cry of José Luis's parents: "Don't forget Cabezas."

11) Fanny Mandelbaum, journalist for Radio Conexión Abierta

It was January 1997. I was spending the summer in Punta del Este and I found out about the murder of José Luis. They called me from the channel to tell me that they had sent me a camera because then president Carlos Menem was coming to present a book by Emilio Perina and give a press conference. Meanwhile, Osvaldo Menendez, a colleague from Radio Mitre who was covering the season, told me that it would be good if all journalists wore a black ribbon to show our pain. I told him it was a wonderful idea. We bought ribbons, pins. I cut them and assembled the black ribbons.

One of Telefe's news chiefs told me not to ask inappropriate questions. I replied that there were no inconvenient questions. If I couldn't ask what I wanted, I wasn't going to ask anything and so I did. I told my colleagues, told them they should ask. I only set the microphone, but we all wore black ribbons.

12) Fernando J. Ruiz. Professor of Journalism and Democracy at the Universidad Austral. Former President of FOPEA (2019 – 2021)

The eyes of Cabezas question journalism, and we can’t hold his gaze. Journalists who marched together in 1997 are now disunited. The discussion about where is the power to be confronted lies and where the truth is confused compasses. That solid professional bloc is today broken and is a weakened community, almost without common references. It is not different from what has happened in other times in history and in many other countries, but this cycle of rupture has gone on too long. José Luis and Gabriel Michi did journalism, not party politics. We must return to that. We know the risks, but democracy demands it.

13) Diego Pietrafesa,Telefe Noticias, Human Rights Secretary of the Buenos Aires Press Union, SIPREBA

Look and count.

You, with your eyes as an offering.

You, against what’s convenient and comfortable.

You, against the owners of everything.

You, with the most human of epics: do what you can, how and where you can, but never less.

You, at the click of a camera against false glamor and other tinsel vanities.

You, an everyday job, flash of dignity in professional, salary, labor and moral precariousness.

You, mate.

We press workers walk in your footsteps.

Jose Luis Cabezas, Present!

14) Lorena Maciel, journalist for Todo Noticias

The crime of Jose Luis Cabezas marked a before and after in my life and, without a doubt, in my professional career. I was barely 20 when Radio Miter trusted me, putting me in charge of covering the case. I offered, obviously, I didn't want to miss anything.

I couldn’t wrap my head around such a crime. Candela's 6-month-old face kept appearing in my mind, his wife Cristina, his other two children, also young. The white car, Gabriel Michi disconsolate, the party at Andreani's, the cellar, the burned boot, the cover of Noticias, and Yabrán, of course, Yabrán walking in a bathing suit and immortalized by a photo taken by Cabezas.

It took not only a year, it took more than 3 years in which my life was intimately linked this research. I asked the radio if I could specialize in legal matters, so I could be in charge of the case.

Thanks to the insistence of journalism and society in general, the truth or almost the whole truth became known. I’m convinced there are many things we will never know. Cabezas was and is an emblem of how far independent journalism can go. The kind that does not respond to any interest other than informing based on evidence.

15) Oscar E. Balmaceda, journalist and writer

I was in Dolores and surrounding areas for 21 months – from February 1997 to November 1998 – covering the investigation into the murder of José Luis Cabezas for La Nación. During that period, I met every one of the characters in the chapter that closed the criminal saga that includes the murders of María Soledad Morales, in 1990, and soldier Omar Carrasco, in 1994.

And what keeps ringing in my memory are some of their sentences: “I'm a criminal, but I didn't kill this boy” (Margarita Di Tullio, alias “Pepita la Pistolera); "They threw a dead man at me" (Eduardo Duhalde, governor of Buenos Aires); "Cabezas was killed because of the work he was doing" (José Luis Macchi, judge of the case).

José Luis Cabezas: Assassinated 25 years ago after he took a photo that upset a businessman accused of corruption. (Photo: CEDOC)

16) Fabio Ariel Ladetto, journalist for La Gaceta de Tucumán. Former President of FOPEA (2011 – 2015)

Where would he have been on Dec. 21, 2001? What look would he have captured of the nine presidents who occupied the Casa Rosada [presidential home] in this century? From which angle would he have immortalized the pandemic?

An absence can be measured by the gaps it leaves, the moments not shared, the unanswered questions...

For this reason, every time we say “José Luis Cabezas, present,” we try to defy his death, condemn his crime and avoid forgetting.

17) Gabriela Carchak, C5N journalist

It wasn't a murder. It was the attempt to muzzle a journalist, a media outlet, a people, a country. But Argentines shouted and shouted loudly. So much so that the photographer killed for doing his work became a symbol of freedom of expression and the collective struggle to sustain it. The crime of José Luis Cabezas marked a before and after not only in increasing awareness of what journalism means, but also in trusting that punishment, although belatedly, reaches those who think they will go unpunished and believe they own other people’s lives.

18) Emilia Delfino, journalist for CNN en Español and elDiarioAR

The photograph that José Luis Cabezas took of businessman Alfredo Yabrán in February 1996, a year before he was assassinated, the image for which he was assassinated, was and is a perfect action of investigative journalism: the exposure of real power, of the powerful hidden, portrayed, illuminated by the eye of a photojournalist, based on previous research work that Cabezas carried out with the team he was part of. Like his action, Cabezas will always be present, like the demand for justice from his family and friends.

19) Gustavo Carabajal, journalist for La Nación

Nothing was the same in my life after the murder of José Luis Cabezas. For more than a year, I covered the case for the newspaper La Nación, I remember an image of his youngest daughter, Candela. She was just over a year old and heard on television the cry of “Cabezas, present” that resounded in one of the marches. She, in her innocence, looked and listened in astonishment, how the demand for justice for her father emerged with energy from the screen.

20) Liliana Caruso, journalist for Policiales y Judiciales in America News and A24

The murder of José Luis shook us without distinction. It was the brutal death of a laborer, a simple photographer who unmasked power. And the case mobilized a society that found out in the most brutal way about the operations of mixed gangs made up of common criminals and police officers. His death still hurts because the feeling remains that the killers got off cheap. A half justice. But luckily, his memory remains: as in a V. Dominic square that bears his name and his eternal eyes, which have the ability to speak.

21) Hipólito Sanzone, covered the case for EL DIA de La Plata

The martyrdom of José Luis Cabezas transcended its own horror, for it allowed society to see all it had not seen or did not want to see. Before that end there was a weave of pressures, restrictions and strong messages to other journalists from other media and in different circumstances and not always by the same actors. The death of Cabezas made it possible to see that not everything in Argentina back then was the “joy” of pizza and champagne. Personally, I got involved because of coverage assigned to me by the newspaper El Día de La Plata in a job that lasted many months. I was left with the impression that the truth revealed had not yet been reached. That there were actors still unpunished and circumstances never properly clarified. Perhaps this matters little when facing the memory of an only victim and his suffering, but it is also possible that his memory deserves that truth revealed that, personally, I still see as elusive.

22) Liliana Franco, journalist at Ámbito Financiero

The murder of José Luis Cabezas was a before and after for local journalism. It meant becoming aware that investigating, denouncing, could cost you your life. A photo, proof of good journalistic work, was the reason why today we have to remember José Luis.

I believe the best way for José Luis’s death to not have been in vain is for us journalists to support the investigative work of our colleagues, to react collectively when power attempts to undermine or ignore them. Let us remember that José Luis was murdered for taking a photo, that is, for doing his job.

23) Cesar Sanchez Bonifato, journalist

The assassination of José Luis Cabezas happened while Carlos Menem was president and our country was sold to illegitimate international interests. YPF and Fabricaciones Militares were sold off, ports were closed, railways were paralyzed, "carnal relations" were maintained with the US, Argentine ships were sent to participate in the foreign invasion of Kuwait, they negotiated with the Lebanese Kadhaffi, the Río Tercero city in Cordoba exploded leaving many compatriots dead.

In this view, there were also Argentine companies involved in shady agreements. A consortium managed by Entre Ríos businessman Alfredo Yabrán was one of the beneficiaries. Our colleague Cabezas discovered him on the Atlantic coast and his image became public. Shortly after, he was assassinated.

In addition, it was reported that Yabrán "committed suicide," but his body was never shown.

The Riojan strongman Menem ended up allying himself with the Kirchners and held a seat in the Senate until his death. “The Cabezas Case” shocked Argentine journalism. It was an emblematic episode, never fully clarified by the Judiciary.

24) Oscar Ángel Flores, journalist for Radio Universidad de San Luis

In San Luis, the murder of José Luis Cabezas created commotion among journalists in the province. Although I did not personally meet our fellow photojournalist, publications from that year allowed me to discover José Luis. Our better-known colleague Gabriel Michi shared with us the full story of that event that shocked the country and exposed a mafia network that exists in Argentina’s power center.

Thus, the Puntano journalists organized themselves and set up a small monument in tribute of José Luis Cabezas in the heart of the capital city. We also promoted events each year under the motto "Let's not forget Cabezas" to continue seeking justice against those who persecute and endanger journalists who run risks in search for the truth.

25) Alicia Miller, journalist and member of the FOPEA Board of Directors

"An invisible and homicidal blow." [Spanish poet] Miguel Hernández thus described the stupor felt before a death of enormous significance. I felt the same way about the murder of José Luis Cabezas, who could have been one of my close colleagues or even myself. In the worst possible way, I learned that courage is not an option but an obligation. And that the constitutional protection of journalism in safeguarding citizen rights will be of no use without a democracy based on respect for those who think differently, without a consensus of special tolerance towards that which opposes, contradicts or singles out.