From the arrival of the first printing press in Chile in 1811 to the present day precarious working conditions and digitalization of media, the history of journalism in Chile is marked by tension between the media, journalists and political power.

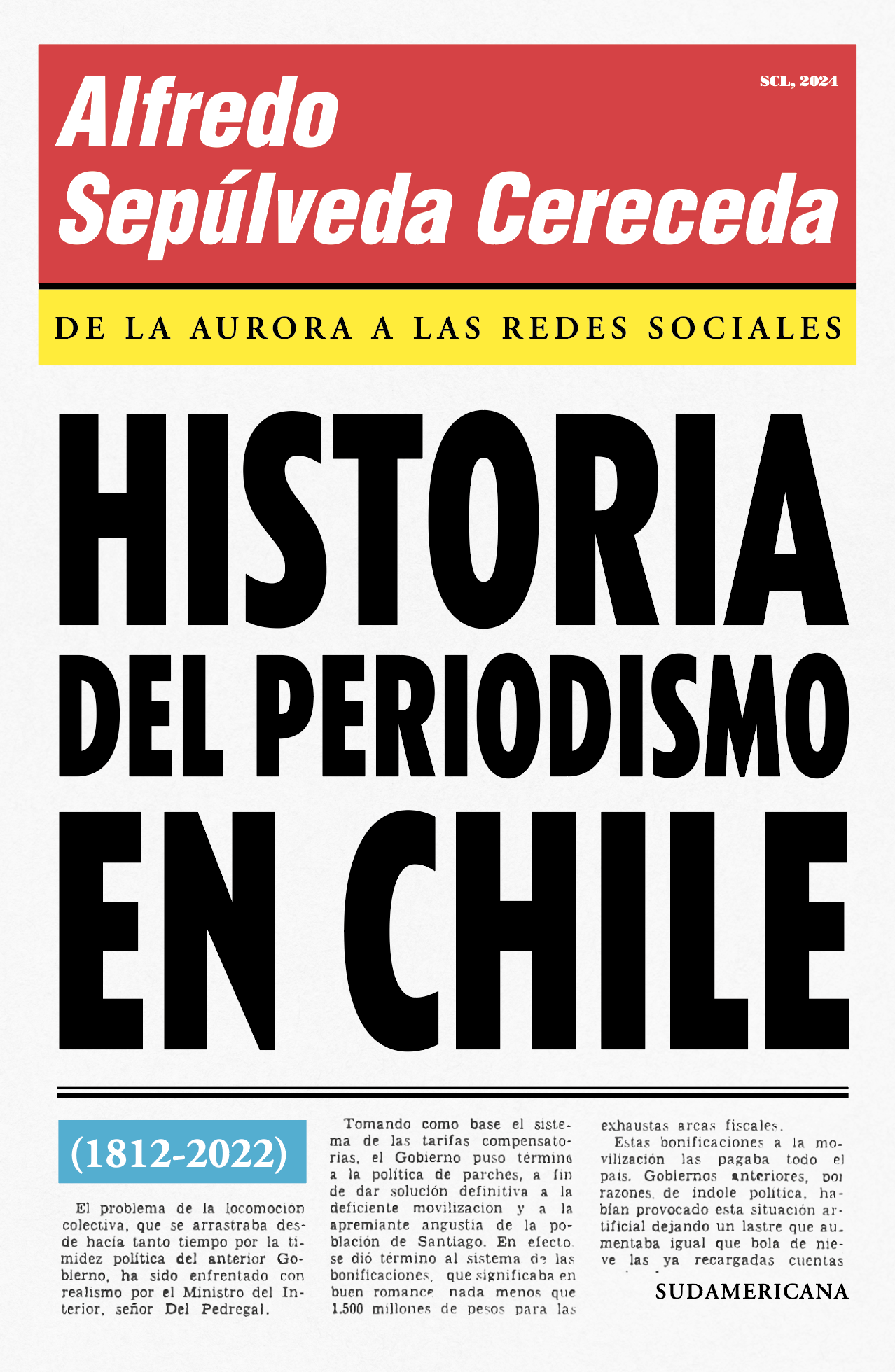

This is the thesis of journalist and academic Alfredo Sepúlveda Cerceda, who has just published the monumental book “Historia del Periodismo en Chile. De La Aurora a las Redes Sociales” (History of journalism in Chile: from La Aurora to social media), by publisher Sudamericana.

In over 500 pages, the author seeks to fill a gap in Chilean historiography: the last history of Chilean journalism was published in 1958, covering everything from La Aurora, the country's first newspaper, until 1956.

Chilean journalist Alfredo Sepúlveda, author of “History of Journalism in Chile: From La Aurora to Social Media” (Photo: Courtesy)

In his book, Sepúlveda reports on the main changes, trends and events in journalism in Chile, from its origins as a propaganda weapon to its professionalization, through the period of polarization during the government of Salvador Allende (1970-1973) and the collaboration of large newspapers with the dictatorship of Augusto Pinochet (1973-1990).

This is not the first foray into history for Sepúlveda, who has been teaching history of journalism at Diego Portales University, in Santiago, for more than 10 years. His previous books include a biography of Chilean revolutionary leader Bernardo O’Higgins, a history of the country and the first 100 days of the Unidad Popular government.

LJR spoke with the author about the history of journalism in Chile, including some of its most controversial moments, and also about the current state of the profession in the country. According to him, “at the heart of the practice of journalism, there will always be politics. That will never change.”

The interview has been edited for clarity and length.

LJR: Why write a history of journalism in Chile?

Alfredo Sepúlveda: I had been dealing with the subject in different journalism schools for about 10 years. Class notes are the basis of the book but I had to research for at least four years what I was missing. The last book that had been published in Chile that covered the topic was from 1958. In other words, in a history of 200 years, 50 needed to be told, and that book did not have radio or television either. In addition, there were a lot of newspapers in the tabloid press, which was very strong in Chile in that period. I think the book is born from an academic curiosity. I have a history as a writer of Chilean historical books, I have other books as well, such as a biography of Bernardo O'Higgins, who was one of the founding fathers of the time of independence. I also have a book on the general history of Chile, and the most recent book is on the Unidad Popular party from the time of Salvador Allende.

LJR: Looking at the history of journalism, what is it possible to say about journalism in general?

AS: It’s difficult to make a broad statement about 200 years of journalism in Chile. It has at least three or four stages in which the definition itself, the ontological definition of the discipline, changes. In Chile, as in many places, journalism begins as a vehicle for political propaganda. It is the revolutionary State of independence that creates a printing press, and with that printing press they begin to produce propaganda for the cause of independence. Afterwards, there is a period in which the great national newspapers are consolidated, and those newspapers in the 19th century have more of a purpose of helping the Chilean State to build progress, as they called it, which is the industrial-commercial vision of the first industrial revolution, and to try to lead the country towards models from northern Europe and the United States. Afterwards, you have a very important period of journalism from political parties in Chile. The political parties from the beginning of the 20th century until 1973 own newspapers and radio stations, and try to exert their influence. However, they do so understanding that they also have to be professional media, they cannot return to the propaganda era of before. And then we have the modern definitions of journalism as the Fourth Branch of the State, an overseer of power, which is more recent. I think that this arises from the creation of university schools of journalism, which in Chile began to appear in the 1950s. So, it is difficult to say that journalism has only one defining trait. However, in the book I tried to come up with a definition, which I think works for everyone and was like a theoretical framework, simply so that I could work. I defined it as a triangle, whose vertices are journalists, political power and the media. The book narrates the relationships between the three, which always have tension.

LJR: How did you develop this triangle theory?

AS: It arose from the fact that I cannot account for each and every media outlet that has existed in 200 years of history. It was a way of limiting. What I was interested in telling was, first of all, the relationship of the media and journalists with political power. I could have gotten into sports, culture, society, but I chose to define this from the point of view of the relations of the media and journalists with political power and vice versa. I believe that this is a constant in the history of journalism in our country and in Latin America. We can say that journalism becomes stronger as a result of the independence processes. That is a political bet. Then you have politicians who are journalists who found their media outlets to carry out their own ideas in opposition to the ideas of others. Then you have the professionalization of journalism, which supposedly fixes things, but politics continues to interfere. It seems to me that politics will always be at the heart of the practice of journalism. We are never going to leave that.

Cover of “History of Journalism in Chile: From La Aurora to Social Media” by Alfredo Sepúlveda

LJR: How did this triangle evolve historically in the years of Unidad Popular and the government of Salvador Allende?

AS: The years of Unidad Popular, from 70 to 73, are a very special situation, as was the dictatorship later, in which basically everything was destroyed. Until Unidad Popular, there was an idea of professional journalism that had been practiced since the 1940s. For this, journalism schools, the College of Journalists, the National Journalism Award were created, and international journalism conferences were organized. This professional idea is linked to the idea of objectivity, the idea that journalism is a discipline that serves to tell about reality in an objective way. But this idea always received a lot of criticism, of course, because it was argued that it was the media owners who assigned coverage and, therefore, journalists were not really free. This was always a tension in Chilean journalism. And journalism schools first begin to teach the first idea, and then the second is incorporated and there is also tension.

When Unidad Popular arrives, and along with it the political polarization of Chilean society, journalism also becomes polarized. The question begins to be less about telling about reality, and more about dismissing or supporting the government of Salvador Allende. The journalists are divided, and they give themselves names. There are the committed journalists, who are those committed to Salvador Allende's project, and the independents, who are those who oppose Salvador Allende's project. The press, through its editorial products and its front pages, undoubtedly contributes to political polarization. However, in the book I discovered, with a solid historiography, that even at that time professionalism was not completely lost. That is, journalistic routines and habits remain. There is sports journalism, there is entertainment journalism, there is police journalism, there is service journalism. If you open a newspaper from that time, you will see that the editorial pages and the front pages are on fire, but in the rest of the paper, it is business as usual.

LJR: During the dictatorship, in terms of the collaboration of the media and journalists with the regime, how was that characterized in general?

AS: During the dictatorship, the left-wing media, those who favored Salvador Allende, literally disappeared. They are annihilated, their property is destroyed and in many cases journalists are murdered by agents of the state. Therefore, there is no strong left-wing press that opposes the military dictatorship. The media that remain are basically the media that were against Allende, and those media are evidently supporters of the dictatorship. Now, as in all things, there are nuances. Things are not black and white. When one says that the media supported the dictatorship, well, yes, they first agreed with the idea that Allende had to be removed, and then they agreed with the idea of the political project that the military represented. However, if they had wanted to oppose it, they could not have done so either, because they would have shared the fate of the left-wing press. It's not that they wanted to oppose it, maybe they didn't want it, but they didn't have the opportunity to do so, because the dictatorship was brutal. So the only way journalism could function in Chile during the dictatorship was to at least not criticize the military junta.

LJR: And what critical voices were there at that time?

AS: The dictatorship lasted 17 years, a long time. There were always voices critical of the dictatorship in Chilean journalism, first in small publications, and in some radio stations that were owned by the Christian Democratic Party. Towards the end of the dictatorship, in the 80s, a very solid opposition press was created, with very good journalism, even investigative journalism, which lived mainly on radio stations and in magazines. They did not have a massive reach like television or newspapers, they did not reach millions of people, but they did have influence.

LJR: What kind of influence and pressure did those small media outlets suffer?

AS: Those small media outlets had influence on politics because the military read them, and the journalists also read them. Now, they had a very bad time, they also had journalists killed and they suffered censorship. There were very ridiculous episodes of censorship. At some point, the dictatorship prohibited publishing images, text yes, but no images, therefore, these magazines had to leave the photographs blank or make small drawings, because they could not publish images. It's absurd, but it happened.

LJR: Do you think there were also critical voices in the newspapers that supported the regime, such as El Mercurio and La Segunda? Was there room for professionals to do some work independently?

AS: No, but there were critical voices. In the book I tell a very early case of El Mercurio, which has particular characteristics. El Mercurio was very proud of the fight they had waged against Salvador Allende, they considered that they had defeated Marxism, they saw themselves as collaborators in a heroic feat. The owner of El Mercurio, Agustín Edwards, at the time of Unidad Popular, lived in the United States. He had gone into self-exile. The newspaper was actually managed by old, tough journalists, journalist-journalists. In 1974, we were very close to a condemnation of Chile in the United Nations Commission on Human Rights, and El Mercurio published the entire resolution, because it found it of journalistic value. El Mercurio also opposed, in principle, the economic direction that the dictatorship was taking and they wrote about it in an editorial. That editorial cost the director his job, he had to leave. However, when the violation of human rights went to the courts, at least it was a news fact that they had gone to the courts. High profile cases of human rights violations, such as a terrible massacre in a place called Lonquén, in which bodies were found two years later, were reported. So, it is more complex. I would tell you that there was support from these great newspapers, El Mercurio and La Tercera, which agreed in the end with the political project of the dictatorship, but there was not complete silence about the crimes of the dictatorship. Something was known, something was published.

LJR: Has there been any self-criticism in these newspapers at any time after the end of the regime?

AS: When El Mercurio turned 100 years old, Agustín Edwards, its owner, gave the only interview he has given regarding the newspaper. The journalist Raquel Correa, who later won the National Journalism Award, asked him the same thing as you: if he had any self-criticism. He said that it was impossible to know the things that happened during the dictatorship and that is why the newspaper did not publish them. One can believe it or not, but the interesting thing is that there is no defense of what was done during the dictatorship period. El Mercurio also participated, knowingly or unknowingly, in actions totally at odds with journalistic ethics, security agencies gave them fake news montages and they published them. It could have been that colleagues knew or did not know, but the fact is that El Mercurio fell into the trap of the security services and published several cases of fake news. It struck me that there was no total defense of what was done during the dictatorship. It is interesting.

LJR: Let's talk a little bit about your own research. What has that process been like?

AS: I have some training in historical research. The writing process itself took about four years. I started in 2019, during the pandemic, and I had a certain foundation from having taken the subject at various universities. The search for historiographic material was long. There is a lot of historiographic material from the Chilean press written by Chilean researchers, very old. I think I have more than 500 references. There was a very old and very long research tradition, but it was disconnected from each other. My task was to put it all together in a more or less chronological order. I didn't have a problem with lack of information. What I do think is missing are personal archives, such as letters from newspaper owners, to more specifically document the links between politicians and media owners. There is a very great tradition of research, but those archives are missing.

LJR: Raúl Silva Castro's book, the most recent book on the history of journalism in Chile before yours, is from 1958. Why has so little attention been paid to the subject since then?

AS: I don't know. Silva Castro probably asked himself the same question. I think his book is the first history of journalism that was done. There are some small things that are written in the 1900s. I think it is because journalism is the largest historical recording machine that exists. Imagine, nowadays every minute we have a record of something. The amount of information that journalism generates is almost unfathomable, and yet there’s very little coverage about it. It never shows what’s under the hood, it doesn't show internal policies, it doesn't show much how it works, and that means there is relatively little light on what we do, on how we do it, on the decisions we make. It's hard to find that kind of material.

LJR: Is the history of journalism in other places similar?

AS: I have the thesis that journalism in Latin America is relatively similar. Practices and routines are similar everywhere. There is no way of doing journalism that is distinctive from Argentina, Brazil or Chile. Routine practices are more or less common, although there are local particularities. In the case of Chile, for example, the tabloid press was left-wing and had relations with left-wing political parties. In Central America, the press is more right-wing and has a right-wing tradition. I think that can be interesting in telling journalism stories in each country.

LJR: How do technological changes influence journalism?

AS: I think that only technological change makes journalism change. Journalism never changes on its own. It changes because it has to. In the 19th century, technological developments within the printing industry generated more newspapers on the streets, and therefore, newspapers had more influence on public opinion. Later, the technology of the electromagnetic spectrum, television and radio, generated a link between journalism and the world of entertainment. Radio journalism needed a new grammar, a new way of describing the news and delivering it. The same thing happened with television and now with the digital world, which is changing the way journalism is done.

LJR: What is the dynamic currently like between the three poles of your book: journalists, the media and political power?

AS: All parties have become precarious. The media has been made precarious by digital. In the last five or six years, 2,000 journalists have left media outlets in Chile. There are fewer newsrooms, fewer journalists, and everyone is working from home. The newsrooms are disappearing. Advertising investment rates have fallen, and that means that journalists are more precarious. There are fewer older journalists, which is important because they maintain cultural tradition and can pass it on in a newsroom. Political power is also precarious due to the threats to democracy, such as populism and polarization. It is not an easy time for the three vertices of the triangle.

LJR: What characterizes journalism in Chile in its best moments?

AS: There are very good experiences. The experience of the dictatorship, in journalistic terms, has brilliant examples of investigative journalism about the dictator, such as the work of Mónica González and Patricia Verdugo. In more institutional terms, the 60s were very interesting because all the country's political positions had their own media outlet, with degrees of credibility and professional practices. It was journalism that did journalism, not just propaganda.

LJR: And what characterizes the worst moments of journalism in Chile?

AS: There are some characteristics of journalism that were very complex. Until the 1950s, it was a very masculine profession, closely linked to nightlife, alcohol, late nights, prostitution and drugs. It was a difficult profession for a woman. The barriers to entry for women only began to fall with the appearance of university schools. There were women in journalism before, but they were absolutely the exception because it was a very difficult world for a woman in the cultural context of Chilean women in the 19th century and the first half of the 20th. It was a very, very tall barrier.

As for moments, I believe that the polarization of Unidad Popular is, without a doubt, notable. There had been polarization before, such as in the 1830s, the period immediately after independence. It can be said that they were polarized newspapers, but they did not have the requirement to be professional. In the 70s, yes, there was a journalistic duty, a journalistic deontology that was there, and the media knew at that time that the journalism they practiced was not in accordance with the current journalistic deontology.