Juan Ricardo Montoya died doing what, according to his colleagues, he loved most: journalism with social impact.

The 55-year-old Mexican journalist lost his life on Oct. 28 while following up on a story he had published the previous day in La Jornada, where he was a correspondent in the state of Hidalgo.

The story was about the return of residents to Chapula, a community in Hidalgo among many devastated by torrential rains in east-central Mexico.

El periodista Juan Ricardo Montoya, corresponsal de La Jornada en Hidalgo, falleció tras sufrir un accidente mientras cubría los estragos de las lluvias en la comunidad de Chapula.#LaOpiniónDePozaRica

Más información en https://t.co/i1OcdNHjML pic.twitter.com/DbiiIhXHPU— La Opinión de Poza Rica (@laopinionpr) November 1, 2025

Montoya slipped down a hillside while walking through Chapula and fell several meters to the edge of a river, according to La Jornada. He suffered a cranioencephalic fracture, and was airlifted to a hospital, where he died hours later, the newspaper reported.

“He was always known for being very inquisitive in his questions, meaning he would strongly challenge authorities and never minced words,” Adela Garmez, reporter for La Jornada Hidalgo, told LatAm Journalism Review (LJR). “He made some officials very uncomfortable, but he was just doing his job.”

Montoya’s death occurred amid a climate emergency that revealed the vulnerability of local journalism in the face of natural disasters.

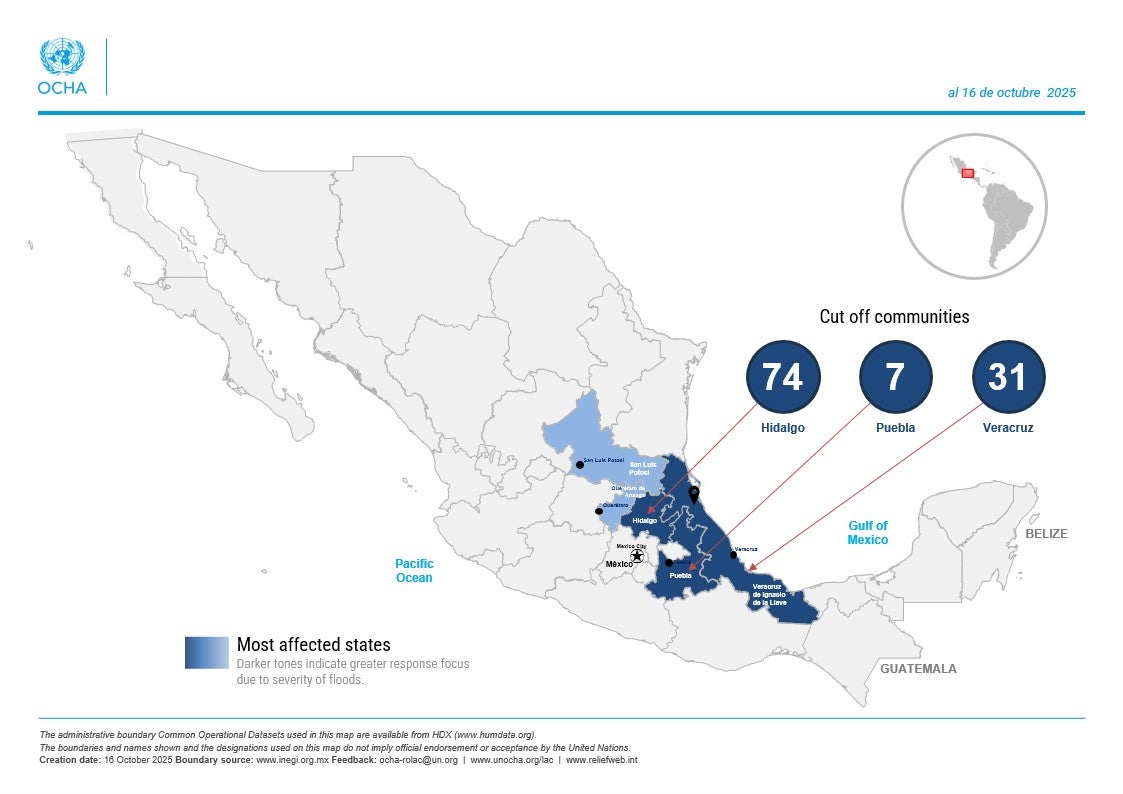

Remnants of Hurricane Priscilla triggered heavy rainfall starting Oct. 6 across much of Mexico. Floods and landslides caused severe damage to homes and infrastructure in the states of Veracruz, Puebla, Hidalgo, Querétaro, and San Luis Potosí.

As of Nov. 1, authorities were still reporting 83 people dead and 16 missing, while 43 communities remained cut off.

The storm isolated journalists and media outlets that, despite the lack of electricity, connectivity, and access routes, sought to keep their audiences informed and to give voice to those who had been left isolated.

“We wanted to go, we tried to go, but the problem was that the roads were closed,” Jorge González Correa, editorial director of La Jornada Hidalgo, told LJR. “A reporter managed to get into several towns, but it was about four or five days later.”

González Correa said that in the first days of the tragedy, his team based their coverage on official data, local authorities, and sources within the government.

Local media were also unable to reach some communities within their own municipalities. Kattia Vera, director of the digital outlet Puntos de Enfoque in Veracruz, said several of her colleagues were trapped in their homes due to flooding and unable to send information to their newsrooms because of power outages.

Kattia Vera, director of the media outlet Puntos de Enfoque, reported on the disaster from Poza Rica, Veracruz, one of the cities most affected by the rains and flooding. (Photo: Pablo Espidio)

As a result, during the first days of the emergency, many local outlets based their coverage on what they gathered from social media, Vera added.

“For those of us in charge of broadcasts, we couldn’t go live because there wasn’t a good internet signal,” Vera told LJR. “Some nearby colleagues who lived on the third floor couldn’t leave their homes until the second day or later, until the water level went down.”

Vera said she considers herself fortunate because in her neighborhood, the water only rose to knee level. While she suffered some material losses, some of her colleagues lost all their work equipment, she said.

The city of Poza Rica, where Vera lives, was one of the hardest hit in Veracruz due to the overflowing of the Cazones River. The blackout lasted at least four days, and reporters had to search for areas with cell coverage and businesses with power generators.

“We had to go to the downtown area,” Vera said. “We had to go to small restaurants or other established places that sold food so we could charge our phones.”

On the night of Thursday, Oct. 9, José Canales, producer and host at the university station Radio UAEH San Bartolo, was unable to return home. It had been raining heavily for the previous three days, and that day things had gotten significantly worse.

Power was out in San Bartolo Tutotepec, the municipality in Hidalgo where the station is located, in the Otomí-Tepehua mountain region. There was also no internet or cellphone service, and access roads were blocked by landslides. The region had been left practically cut off.

That night, Canales had to sleep in one of the station’s studios, which belongs to the Autonomous University of the State of Hidalgo. When he woke up the next morning, he realized the magnitude of the emergency.

“Three of my colleagues who also travel from other municipalities to the station couldn’t make it because a river had overflowed,” Canales told LJR. “Another colleague didn’t show up for work either because she was the one most affected: the river swept away her house and everything in it.”

Canales and the only colleague who managed to reach the station decided to go out and document what had happened in San Bartolo Tutotepec using their phones. They found total devastation: destroyed homes, roads blocked by debris, overturned vehicles, and sections of highways torn apart.

Back in the studio, they began broadcasting on both the radio and Facebook Live to share what they had seen. The station was able to keep operating thanks to a diesel generator and an alternate satellite internet service.

“I can’t say that we actually designed a strategy to cover everything that happened because we were immersed in it,” Canales said. “We simply kept moving as the hours went by.”

They immediately began receiving messages via WhatsApp and Facebook Messenger from people outside San Bartolo Tutotepec asking about relatives in the municipality with whom they couldn’t communicate or whose whereabouts were unknown.

The number of messages became overwhelming, Canales said, so they decided to open the station’s doors to residents so they could charge their phones, connect to the internet, and contact their families.

Soon the station filled with people, some coming from communities two or three hours away, he said.

René Martínez, director of Radio UAEH San Bartolo, and other members of the team went out to get diesel fuel to avoid running out of electricity. (Photo: Screenshot from Facebook Live)

“All areas of our station were full of people connected. There were times when we ran out of outlets,” he said.

In turn, those people became sources of information for the radio. They reported on the damage left by the storm in their communities, which the media had not yet reached.

Messages also began arriving at the station from people asking for help, reporting shortages of food and medicine, or asking for help to take relatives to the hospital, Canales said.

“We became spokespeople for the needs that were emerging after Hurricane Priscilla,” Canales said. “Our live broadcasts also became moments when people could ask questions, and we would answer them in real time.”

As the hours passed, the diesel for the generator began to run out. The station director decided to limit broadcast time to six hours a day, in two-hour segments.

“We wanted to keep our diesel as long as possible because we said, ‘We can’t go a single day without saying something about what’s happening here,’ ” Canales said.

On Monday, Oct. 13, when members of the team hiked for nearly an hour to bring back diesel, power was restored in San Bartolo Tutotepec.

During those four long days, Radio UAEH San Bartolo was the only outlet covering the emergency in the Otomí-Tepehua mountain region, said Canales, who stayed at the station for seven days.

The tragedy underscored the value that a university station like Radio UAEH San Bartolo has for the community, Canales said.

“I believe that after this, people will value more the importance of having a university radio station,” he said. “They’re realizing it’s a medium they can use, that its value doesn’t just stay inside the studio.”

But the experience also taught them lessons, such as the importance of leaving the studio more often and having direct contact with the people, Canales said.

“This experience showed us that we are a very important element and that we need to demonstrate more commitment outward, toward our audience,” he said. “Our way of helping was this, being their voice to the outside world. Being the cry for help from this region that, historically and sadly, is one of the most forgotten.”

Floods and landslides caused severe damage in the states of Veracruz, Puebla, Hidalgo, Querétaro, and San Luis Potosí. (Photo: United Nations OCHA)

This article was translated with the assistance of AI and reviewed by LJR staff