After leaving a rally of supporters of Brazil's President Jair Bolsonaro under police escort, CNN reporter Pedro Duran figured the worst was over. After all, he had been attacked and cursed by demonstrators and without the protection of the police, the violence could have escalated further.

However, with the repercussions of the case in the days following May 24, the journalist began to suffer a second type of attack: digital.

“Some people came after me on other social networks like Instagram and Facebook. If the physical attack was not enough, there was also the virtual one. It had happened before on other occasions. When the attack comes through these means I feel like I have my privacy violated because they are environments that, especially in the pandemic, I have used to keep in touch with my family and friends,” Duran told LatAm Journalism Review (LJR). “There was no threat because if that happened I would go to the police immediately, but curses and insults, mostly from spurious profiles.”

A survey by the NGO Reporters without Borders (RSF, for its acronym in French) and the Technology and Society Institute of Rio (ITS-Rio) shows that social media has become hostile territory for the press in Brazil. In a three-month period, between March 14 and June 13, 2021, researchers identified 498,693 attacks on journalists and the press in general in the country. A fifth of the total attacks came from accounts with a high probability of automated behavior, i.e. robots.

“If you have a user who doesn't have a profile picture, it's just an avatar. That has a series of numbers in its handle. If the profile name doesn't match this handle, and if that user shares 200 times in 60 seconds. All of these are features that will enhance this user's final grade. The closer to 100, the greater the probability that this user will be identified as having a high probability of automation,” Thayane Guimarães, senior researcher at ITS, explained to LJR. "Frequency weighs heavily for this Pegabot account [which measures likelihood of automation], precisely because it's impossible for it to be tied to an authentic human activity."

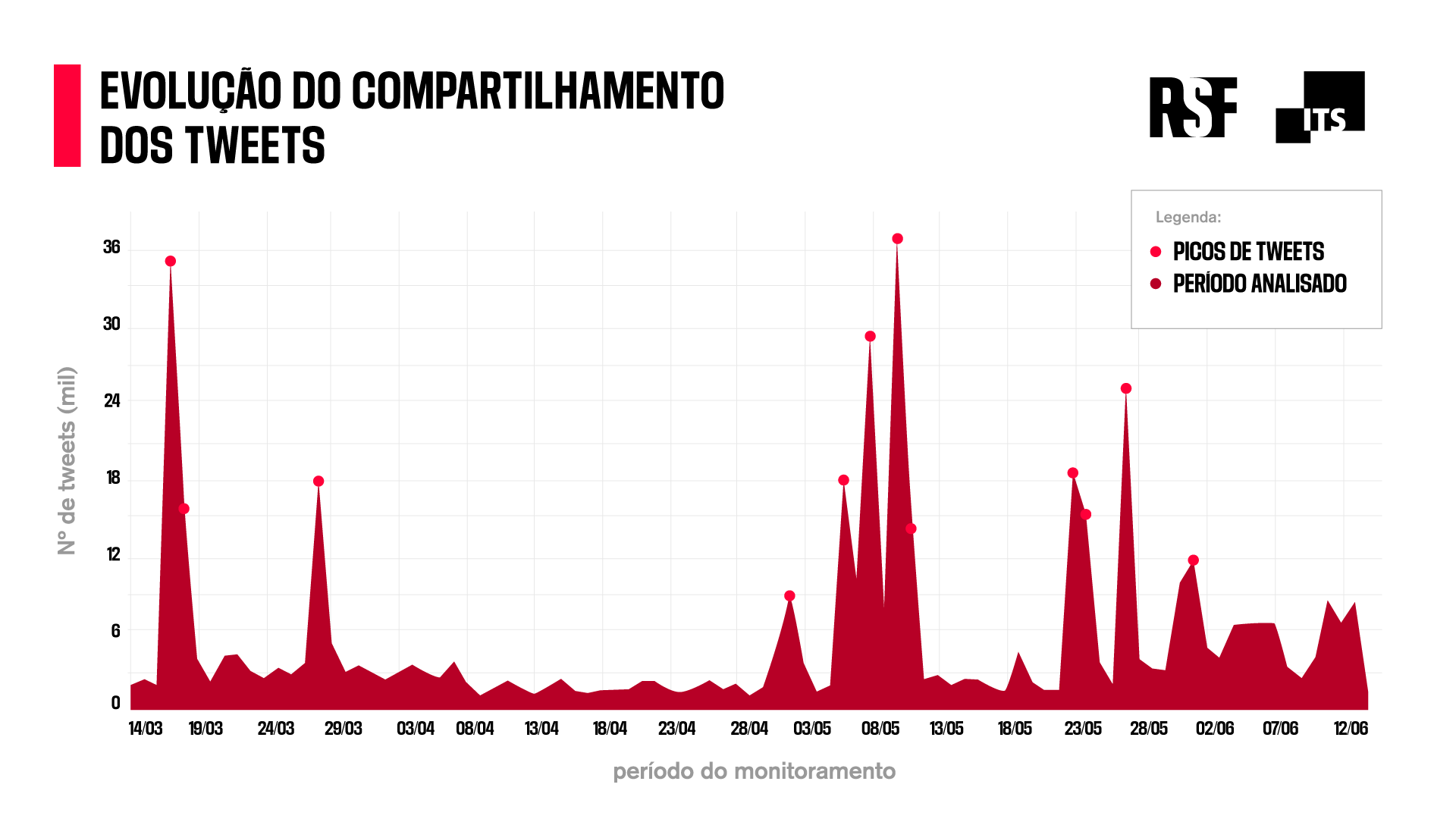

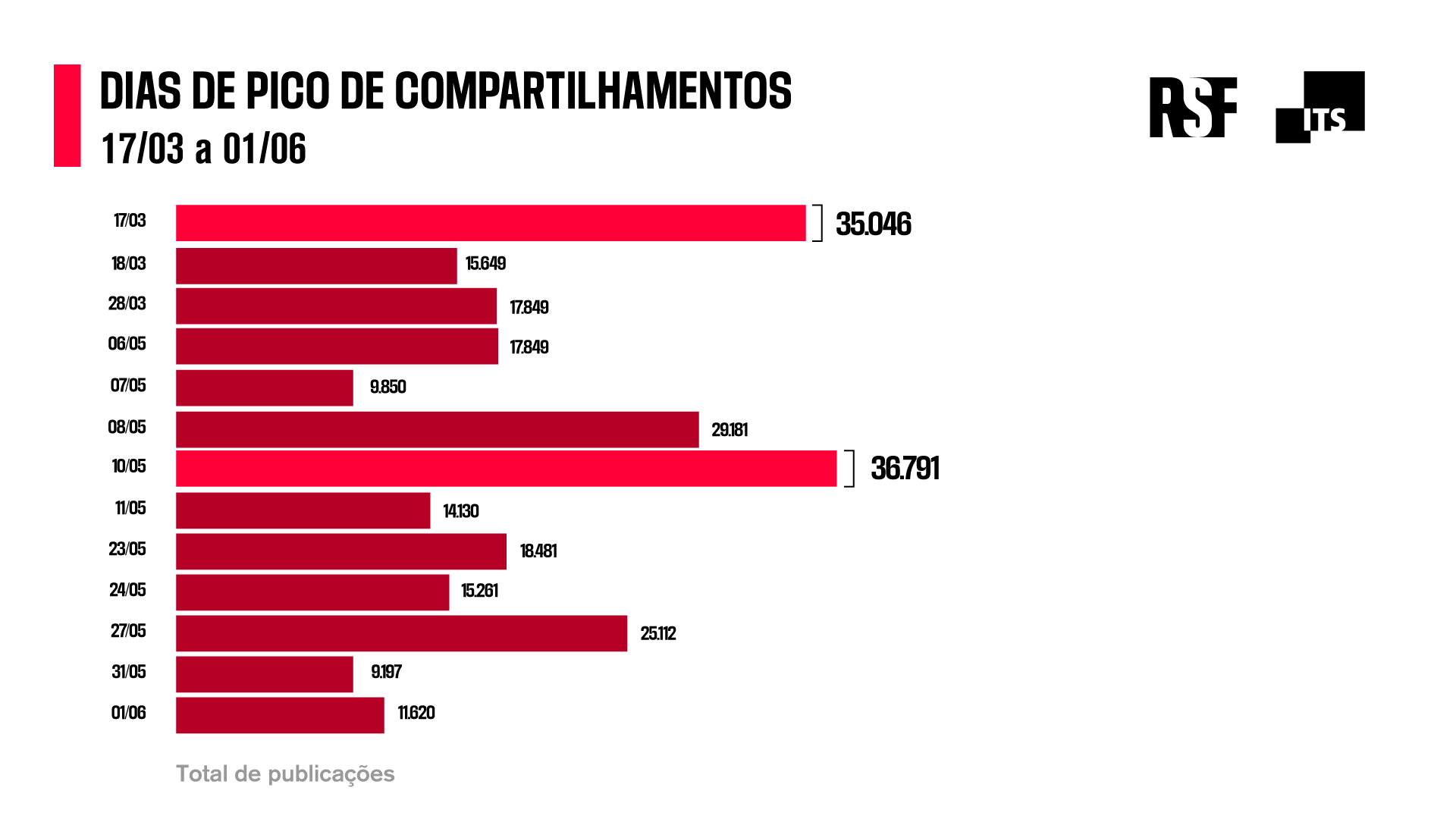

More than half (51%) of Tweets are concentrated in 13 peak days, which represents 14 percent of the total for the three-month period. Click to enlarge the image. Credit: RSF and ITS

According to the report, this automation raises the suspicion that attacks on journalists are systematically planned and coordinated. In the study, data were collected from tweets mentioning a set of five hashtags, some targeting specific news outlets: #imprensalixo (trash press), #extremaimprensa (extreme press), #globolixo (Globo trash), #cnnlixo (CNN trash), and #estadaofake (Estadão fake). They were used by 94,195 Twitter users. Of these, 3.9 percent are possibly automated profiles -- however, they represent 20 percent of attack volume.

"It does not mean that the organic movement does not exist, but when there is an incentive via robots for these messages, for this subject to really be on the agenda, they also end up adding fuel to the fire so that more messages appear on the network from the real profiles. There is this impetus, this springboard via automated profiles,” Guimarães said.

The study also identified peak engagement moments with monitored hashtags associated with episodes of digital harassment against the profiles of some journalists, such as Maju Coutinho (TV Globo), Daniela Lima and Pedro Duran (CNN Brasil), Mariliz Pereira Jorge (Folha de S. Paulo), and Rodrigo Menegat (DW News).

The day with the highest number of posts was May 10, with 36,791 records, following the publication of the report “Orçamento secreto bilionário de Bolsonaro” (Billion-dollar Secret Budget of Bolsonaro), in Estadão, about a parallel budget scheme, used to release funds for parliamentary amendments.

“The systematic attacks on the credibility of the press are directly linked to the disinformation strategy mobilized by the government. By demoralizing journalists and the media identified as critics, the government essentially seeks to expand its control over public debate,” Emmanuel Colombié, head of the Latin America section of Reporters Without Borders, told LJR.

Colombié also said that digital campaigns of attacks on the press promote the stigma of journalists as enemies, which can turn digital violence into physical violence.

“In a political context of intense polarization, this idea mobilizes the hatred of certain groups, transcends the digital sphere and materializes in other types of violence, ridicule, expulsion from demonstrations, offenses in public environments and potentially physical aggression,” he said.

The spikes in engagement with monitored hashtags also coincide in most cases with a strong movement of targeted attacks on journalists. Click to enlarge the image. Credit: RSF and ITS

The study also identified an important gender element in the universe of monitored attacks: the total number of tweets mentioning female journalists was 13 times higher than that of their male counterparts.

“One thing I've noticed is that these attacks are increasingly organized. Before ,they seemed organic, but now I see an articulated movement, and it takes on a very large proportion,” Folha de S. Paulo columnist, Mariliz Pereira Jorge, told the researchers.

“A very relevant point of the report is precisely this expression of misogyny and gender violence online. This is something we have been trying to monitor for a long time. This relationship of freedom of expression, and specifically, in relation to women journalists, and this bot movement. This is central to our research, realizing how not only the press, in general, is considered an enemy of the federal government, to the point of motivating these mobilizations, but also how these women are because they have power with their speech, with doing political analysis, etc.,” Guimarães said.

According to Colombié, due to the very nature of their activity, journalists work with a high degree of exposure, even though the vast majority do not have the status of public figures. And, according to him, this exposure can easily be used by groups to promote some kind of retaliation or intimidation:

“When the target of an attack, journalists can and should seek all kinds of support, starting with the media outlet itself, their editors, colleagues; but also from lawyers, unions and the entire community of civil society organizations that are mobilized in defense of press freedom. The construction of a support network capable of bringing ways to overcome such situations is one of the main strategies to overcome these situations.”