How do journalists' working conditions impact the quality of information that reaches the public? This is what Brazilian researcher and journalist Janara Nicoletti wants to answer with the model developed in her study “Impacts of the precariousness of the work of journalists on the quality of information.” The study won the 2020 Adelmo Genro Filho Award from the Brazilian Association of Researchers in Journalism (SBPJor, for its acronym in Portuguese) as the best doctoral thesis of the year.

“The precarious working conditions and the [poor] performance of the team is something that every journalist already feels, knows that it happens. But, in a way, it is something like the norm of the profession: you will find a way to get by, you will find a way to cope, to make the story,” Nicoletti told LatAm Journalism Review (LJR).

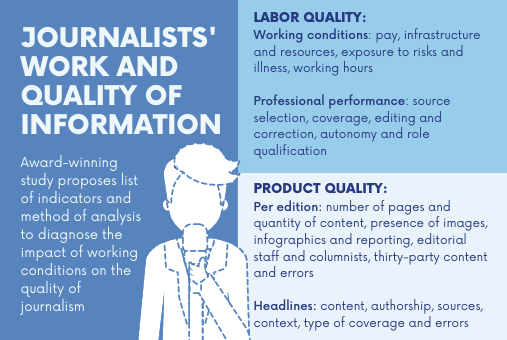

She developed an analytical model that assesses working conditions, journalists' performance and product quality. This is done based on an index system that gives rise to two scales: quality of work and quality perceived in the product.  The labor quality scale was measured through an opinion survey with 117 journalists from five Brazilian states: Minas Gerais, Rio de Janeiro, Rio Grande do Sul, Santa Catarina and São Paulo. The scale of perceived product quality was measured via content analysis. For her doctoral thesis, Nicoletti analyzed 28 editions of a regional newspaper from a group with operations in Rio Grande do Sul and Santa Catarina in the years 2012, 2015, 2018 and 2019.

The labor quality scale was measured through an opinion survey with 117 journalists from five Brazilian states: Minas Gerais, Rio de Janeiro, Rio Grande do Sul, Santa Catarina and São Paulo. The scale of perceived product quality was measured via content analysis. For her doctoral thesis, Nicoletti analyzed 28 editions of a regional newspaper from a group with operations in Rio Grande do Sul and Santa Catarina in the years 2012, 2015, 2018 and 2019.

One of the journalists who responded to the survey has been in the market for ten years. He witnessed the deterioration of working conditions in the newspaper where he worked, first at a branch in the interior and then in the capital. With constant staff reductions, he had to take on coverage for dismissed colleagues, which led to increased workload to maintain the quality of his work.

“I was at a branch in one city, but the branch closed and went to work in another city. And from there I needed to continue covering the first and now the second as well. (…) There were two reporters and a photographer who was also the driver. It was very common for us to share the same car to do our daily stories, so when one was talking to a source, the other was waiting in the car,” the journalist told LJR*.

Another survey respondent mentions the question of autonomy, or the lack of it, as a major factor to describe one of the barriers faced in the daily life of a journalist. This is because, according to her, there is direct interference from the company's management in the choice of sources that are heard by reporters.

“We stopped citing sources because the company didn't want to. There is a very clear direction, which is imposed. It's frustrating,” the journalist told LJR. In a situation where she managed to convince the management to listen to the counterpoint, the result was not what was expected: “In the end the source did not want to speak, because he knew that he would be slaughtered, so the source did not even want to defend himself.”

The two situations appear in the quantitative survey: most workers reported that they favor official sources, coverage occurs mainly from within the newsroom, there is little time to check and investigate. In addition, they perceive less autonomy and greater interference with their work.

In the group surveyed, the quality of work of most journalists (67.5%) is considered reasonable – between 0.41 and 0.60 on the scale of up to 1. For 10.03 percent, the result is poor (0.21 to 0.40) and only 21.4 percent scored above 0.61, that is, an index considered satisfactory.

Researcher and journalist Janara Nicoletti developed a model to analyze labor conditions and the quality of journalism. Photo: courtesy

“The ideal here would be a score starting at 0.61 in which a certain balance can be perceived between all dimensions related to the work environment and routines, and also a good performance that represents professional practices appropriate to good journalistic quality, like copy editing of information or taking the time to review what you wrote,” Nicoletti explained.

In the content analysis, the quality perceived in the product fell from 0.66 in 2012 (considered good) to 0.18 in 2019 (classified as terrible on the scale).

“Over the years, there has been a significant drop in the number of journalists (reporters, editors and freelancers), columnists and photographers involved in each issue (more than 80 percent over the entire period). There was also a reduction in pages per edition over the period, which helps to understand the business crisis and justify the drop in professionals. However, the amount of journalistic content per edition increased between 2012 and 2019, which goes against the previous sentence and highlights a precarious scenario,” Nicoletti said.

According to the researcher, "the precariousness issues verified in the product are affirmed by the long working hours, with high productivity, reduced staff, frequent overtime and increased work intensity in the last year, among other verified indicators." The researcher's objective is to further develop this method so that it can be applied in other more comprehensive studies and also adapted to different regional and national realities.

Taboo subject

The research sheds light objectively on a subject that is not critically discussed in newsrooms: the relationship between working conditions and journalistic quality. Nicoletti's research came from her own professional experience as a reporter and editor at a TV station and from the search for objective arguments to understand how working conditions would interfere with the quality of her journalistic work.

“This thesis was born out of my attempt, as a journalist, to try to show this reality in a more concrete way. (…) There are several studies that show the relationship of working conditions and the quality of what is done by the journalist, but without numbers,” Nicoletti said.

This is not only because of the difficulty in objectively quantifying subjective criteria, but also because of the very nature of journalistic activity and its inherent stress and unpredictability, and also because of the fear that participation in something like this could be viewed as critical by employers, and result in being blacklisted.

“When we are talking about a company that puts journalism front and center, that has a role of really helping to promote democracy with journalism, seeing this downsizing of teams that is done and the way it is done, is something that makes no sense from a business perspective,” Nicoletti said. "It is a business strategy that is not working, which is causing a drop in quality of journalism, and perhaps this is also related to the drop in credibility that journalism is experiencing."

For the general coordinator of the Adelmo Genro Filho Award, Marli dos Santos, Nicoletti's research innovates by proposing a list of indicators that can be combined with the diagnosis of working conditions and quality of journalism, with applications in the labor market, for unions and journalism schools. "

Investigating this relationship is essential to ensure that journalism is a competent interlocutor for democracy, fulfilling its social commitment. This allows us to establish a dialogue with society, in addition to being a very important contribution of the academy to journalism," she told LJR.

Furthermore, at a time when the press is under pressure from political demagogues and the public on the one hand, and the crisis of the business model on the other, showing clearly how structural issues affect the quality of information can be seen by some as an attack that weakens journalism even more, at a time when there is little defense. However, for Rogério Christofoletti, a researcher responsible for the Observatory of Journalistic Ethics (Objethos), expanding the debate is fundamental to reinforcing the social function of journalism.

“In Brazil, the debate about quality in journalism almost always takes into account only the structure of newsrooms and the ability of companies to offer their products and services. But the production conditions also cover the working conditions of the professionals involved,” he told LJR. “Janara's thesis brings these poles closer together, allowing for the recognition of the weight of journalists in the final result of what reaches the public. This broadens the horizons of the discussion on the topic.”

Janara Nicoletti’s entire thesis is available (in Portuguese) here.

* Journalists asked not to be identified as they are still active in the market and fear suffering reprisals from employers.