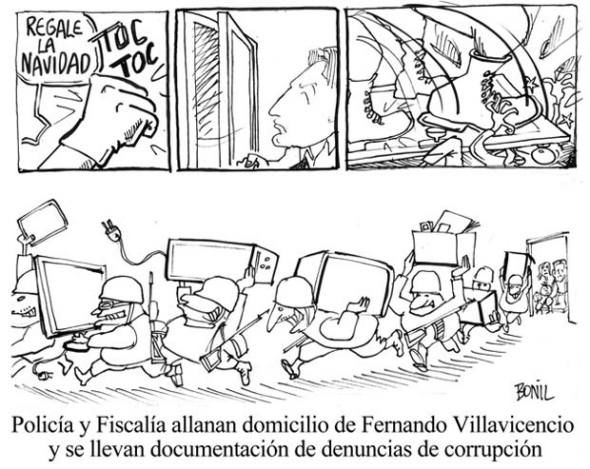

Editorial cartoon by Xavier Bonilla published on Dec. 28, 2013 in Ecuadorian newspaper El Universo with the caption “Police and prosecutors search Fernando Villavicencio’s home, take documents on government corruption.”

By Norma Garza

The Ecuadorian government has asked cartoonist Xavier Bonilla, known as Bonil, to appear before the Superintendent of Information and Communication and explain the contents of an editorial cartoon published in newspaper El Universo that officials are calling defamatory. Seven months after Ecuador’s new Communications Law came into effect and created the office of the Superintendent, Bonil is the first media worker to be summoned by the new agency.

El Universo published Bonil’s cartoon on Dec. 28, which depicted a police search the day before at the house of Fernando Villavicencio — a journalist and advisor to an opposition legislator — and alluded to police corruption.

The subpoena calling the cartoonist to testify is based on a report by the Superintendent’s office that accuses Bonil of perverting the truth and promoting social unrest.

Bonil responded with a seven-page document in which he explains the nature of his job.

“A cartoon is humorous creation so it cannot be required to be, or judged under, truthful and impartial representations of reality,” he wrote. “It’s a form of humorous art, subjective both to the perspective of the person who has created it, and to that of the person who looks at it.”

Ecuador’s President Rafael Correa has referred to Bonil as a “sicario de tinta” — a hit man who uses ink as his weapon — and said he was happy to have “a communications law that protects us, even if they try to pretend they’re funny cartoonists to spew their hate.”

The deputy director of news website Hoy, José Hernández, criticized the government’s actions against Bonil. In an opinion piece titled “If we laugh, do we need a lawyer sitting beside us?” Hernández wrote: “when the powerful want to make humor politically correct, it immediately turns itself into something laughable.”

This is not the first conflict to erupt between the president and the cartoonist. A year ago during his presidential campaign, Correa filed a complaint with the National Electoral Commission over the publication of a cartoon that he thought damaged his image. Correa demanded El Universal let him respond, and offer an apology. The newspaper did not apologize, but it did publish the then-candidate’s complaint. Two years ago, candidate Correa won a defamation suit against the newspaper, sending three editors and a former editor to jail for three years along with a fine of $40 million. Correa later asked for the sentence to be annulled.

The director of the Andean Foundation for the Observation and Study of the Media (Fundamedios), César Ricaurte, said that his organization’s database of restrictions against the press, compiled since 2008, shows Correa as the top offender. “The president sustains a constant and systematic stigmatizing discourse against journalists and media workers. He has used the harshest adjectives with journalists and on his Saturday program he identifies them by name, and shows off their photos. Correa does that when he doesn’t like some bit of criticism or an op-ed.”

The next step in Bonil’s case is a court hearing when both sides will present evidence and any relevant documents. At the end of the week, the Superintendent will sanction Bonil, or archive the case.

According to the country’s communications law, the office of the Superintendent of Information and Communication “is a mechanism of surveillance, auditing, intervention, and control” with the capacity to investigate complaints, to sanction, and to supervise implementation of the law.

The controversial law was approved last year and has been widely criticized by international organizations since then. Human Rights Watch said that the law restricts the press and, according to an OAS alert, it has created an intimidating effect among the press since it legitimizes “lynching the media.”

This post was translated by human rights investigator and journalist Patrick Timmons, editor of the Mexican Journalism Translation Project (MxJTP). Follow him on Twitter @patricktimmons.