"No more stories from Jornal Nacional." This is how Jair Bolsonaro, then president of Brazil, responded on June 5, 2020 to journalists who questioned the delay in releasing data on the COVID-19 pandemic. In the first week of June 2020, when Brazil was setting new records for deaths from the disease every day, the Ministry of Health started publishing daily numbers of the pandemic in the country later and later. The delay made it impossible to release the data on early evening TV news programs, such as Jornal Nacional, on TV Globo, and in printed newspapers the following day.

In addition to the delay, on June 5, 2020, the federal government even took the data portal offline. When it went back online, almost 20 hours later, the portal started presenting only the deaths and cases registered in the last 24 hours, as well as a daily number of cases of people who had "recovered" from COVID-19. The portal no longer showed the accumulated total number of deaths and cases registered since the beginning of the disease in Brazil, and neither did it include the regional distribution of data and the fatality rate. The option to download the complete data in an accessible format also disappeared.

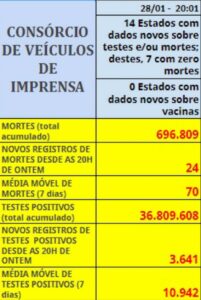

The statement of the then-president showed that one of the government's intentions in changing the way data was released was to undermine the work of the press. Faced with an unprecedented health crisis, and with Brazil rapidly climbing positions in the world ranking of COVID-19 cases and deaths, the federal government acted to hide the reality of the pandemic in the country. Six Brazilian news outlets responded by establishing a collaborative consortium dedicated to transparency in reporting COVID-19 data for the next 965 days, between June 8, 2020, and Jan. 28, 2023.

The consortium of news outlets united journalists from the online sites g1 and UOL and newspapers O Estado de S. Paulo, Extra, Folha de S. Paulo, and O Globo. Their news directors articulated the collaboration in the days following the first COVID-19 data blackout promoted by the government.

"The numbers [released by the Ministry of Health] were no longer reliable. We no longer knew if we were informing the truth or not," Marcos Sergio Silva, news editor at UOL, told LatAm Journalism Review (LJR). According to him, UOL began to discuss alternatives to the federal government's figures, such as collecting the data from each state or resorting to the National Council of Health Secretariats (Conass, by its Portuguese acronym), which had been publishing the data informed by the state health secretariats.

Silva said that when he was informed by UOL's board about the conversations to establish a collaborative research among the six news outlets, he contacted journalists from the other newsrooms. One of them was Daniel Bramatti, editor of Estadão Dados, the data journalism hub of the newspaper O Estado de S.Paulo.

The last report created by the consortium (Courtesy)

"From the moment news editors decided to make a joint response to this data blackout, different journalists in each newsroom were tasked with making the collaboration work," Bramatti told LJR. These data journalists usually know each other and hang out at events and take courses together or have that in common, and they maintain a communication in the real world and in the online world that brings them together."

According to Bramatti, because of this previous understanding, "we quickly formed a group and a work method." This consisted in the use of a collaborative Google Docs spreadsheet, shared and updated by the journalists involved in data collection. Each news outlet was responsible for collecting the data from five or six Brazilian states from their Health Secretariats.

The first report created by the consortium, posted at 8 p.m. on June 8, 2020, brought together the number of deaths and registered cases of COVID-19 in Brazil and in each state in the previous 24 hours, as well as the accumulated total of cases and deaths since the beginning of the disease, which had disappeared from the Ministry of Health's dissemination portal. It also informed about the 20 cities with the highest mortality and with more registered cases during a period and the rate of occupancy of ICU beds in each state, among other data.

"It was a very exciting moment, on June 8, when right there and then I was seeing something historic and important — our team standing up to the lack of transparency of those who should provide [the data]," Silva said.

Bramatti commented that, at first, a problem faced by the teams was the discrepancy in the pattern of data disclosure by each state. "There were differences in schedule, some took longer to release, some didn't have a daily release," he said. The journalists were talking to state agencies and Conass explaining the need to standardize the data. According to Bramatti, "almost all [the requests regarding the disclosure of the numbers] were accepted."

Data gathered by the consortium presented on TV Globo's news program (Screenshot/TV Globo)

With the start of COVID-19 vaccination in Brazil in January 2021, the consortium also included in the report data on the progress of vaccination coverage: The number of people vaccinated and with which dose among people with comorbidities, general public, minors under 18, children, and infants.

"The work actually got more complex over time," Bramatti said. "Each time I had more and more data to collect and disseminate. Each news outlet prepared and adapted in its own way. For example, at Estadão, we tried to automate collection routines whenever possible. Whenever data was published in a way that allowed them to be read by a machine, we did this collection also in an automated way," through functions in Google Sheets spreadsheet that scraped the data off of the states' websites, he said.

Silva and Bramatti explained that the data collected by the consortium together with the states were the same as those passed on to the Ministry of Health to be disclosed by the federal government. According to UOL's reporting chief, the idea "was not to compete with the federal government or with Conass." "In fact, the consortium was a kind of 'safeguard,’ so that the disease numbers would continue to be disclosed," Silva said.

"The consortium aimed to prevent the federal government from failing to present the data from the [Ministry of Health] system, which was fed by the municipalities and the states," Bramatti said. "The Ministry of Health, at that moment, was the 'centralizer' of the data, and they [the Bolsonaro government] tried to usurp the right to hinder the work of the press and to leave the population less enlightened about what was happening, in the dark. The consortium reacted to this and went after the data in the states that fed the system, so they could take this data and pass it on to the consortium, without it having to be authorized in any way or depend on the Ministry of Health," he said.

The day after the first report was released by the consortium, the Supreme Court ordered the Ministry of Health to reinstate the daily disclosure of data on the COVID-19 pandemic, in its entirety and in the terms in which they had been presented until June 4, 2020.

Even so, the consortium continued collecting the data daily until Jan. 28, completing two years and seven months of uninterrupted work.

"There was a risk that at any moment the president [Bolsonaro] or the health minister would change his mind and decide that they would not release the data," Bramatti said. "The consortium was created as a response to a threat of data blackout, and it ended at a moment when that threat practically ceased to exist, with the new authorities taking office [on Jan. 1, 2023, under President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva] and who show no intention or tendency to seek to hide the real pandemic data from the population," he said.

However, should this trend change and the current government reduce the level of transparency in COVID-19 data in Brazil, the consortium must return, Bramatti said. "[The consortium] was formed to defend a principle, which is the principle of transparency, and all governments should be transparent. When a government is not transparent, there should be a response from the press, if possible jointly, so that the problem is solved," he said.

For the editor of Estadão Dados, the main lesson left from the consortium is in fact the value of transparency, especially in relation to a health crisis of the magnitude of the COVID-19 pandemic. In Brazil alone, as of Feb. 13, 2023, at least 697,674 people have died from the disease. The country, which has 2% of the world's population, so far concentrates 10% of the total deaths caused by the SARS-CoV-2 virus worldwide.

"We need to take action every time governments try in any way to hinder access to information that should be public and is not always so, information that has value to society, during a pandemic. If people do not know what is going on in the day-to-day life of a pandemic, they are less likely to make a risk assessment and may make wrong decisions, with direct consequences for their lives and the lives of their families. A wrong decision in a pandemic can even lead to someone's death. So it is very important that all the data be public," Bramatti said.

Another lesson learned from the consortium concerns the value of collaborative work. In this case, it was a collaboration among competing news outlets, which came together in the extraordinary context of a COVID-19 pandemic and a denialist government to fulfill their mission to inform. This value was recognized by the National Association of Newspapers (ANJ), which in December 2021 gave the ANJ Press Freedom Award to the consortium of news outlets and to Comprova, a collaborative fact-checking project fighting against misinformation that brings together 24 Brazilian news outlets.

According to Bramatti, at least 113 people have worked in the consortium at some point.

"None of the newsrooms alone would have been able to collect [data] every day from the 27 state secretariats [of health]. This would’ve been a huge task, involved a very large team, and it would’ve possibly been unfeasible to do this work in isolation. When five or six news outlets were involved, the work was shared, and the information that was shared was even checked by more people," he said. He highlighted that on more than one occasion it had been possible to identify inaccuracies in the data and avoid the dissemination of erroneous information due to the many eyes involved in the work.

Silva also underlined that the work in the consortium was developed in "a very democratic process," of shared conversations and common agreement in decision-making. "Ego was left outside. There was no largest or smallest [news outlet] within the consortium (...) If a person had any difficulty working with the spreadsheet, there was always another person willing to help," he said.

Bramatti said he hopes the consortium's legacy will be to value collaborative work among newsrooms.

"I hope that in the future, when there are topics of public interest and coverage that are difficult to do with just a few people, that a collaborative way of working will again be contemplated. When the public interest is involved, sometimes competition among media outlets doesn't make much sense. It is better to join forces, to work together, in search of a result, than to compete and many times not even be able to scratch the surface of a complex topic or of a mountain of data that is often inaccessible and impossible to analyze if there aren't many people working on it," he said.