This is the first story in a series on covering violent conflict in Latin America.*

(Illustration: Pablo Pérez "Altais")

It’s been almost four years since Ecuadorian journalists Javier Ortega and Paúl Rivas, along with their driver Efraín Segarra, were abducted in Mataje, a town on Ecuador's border with Colombia.

They worked for the newspaper El Comercio in Quito and had traveled to the province of Esmeraldas to cover an escalation of violence in the area, unleashed by dissident groups of the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia, or FARC, who had not agreed to demobilize after the peace accords and had crossed to Ecuador where they sought to control territories for drug trafficking.

The increase in violence included terrorist attacks that were responded to by the governments of Colombia and Ecuador. The Oliver Sinisterra Front, a dissident group of the FARC, abducted the journalists on March 6, 2018, to pressure the government to stop the persecution. Weeks later, on April 11, the three El Comercio workers were killed.

The three journalists were not prepared to cover conflicts involving armed groups, according to their own colleagues.

In Latin America, armed groups can even be combined. There are gangs that are drug traffickers, there are also guerrilla groups that engage in criminal activities to finance themselves. They are generally armed groups in conflict with authorities or with each other. The combination of variables presents a challenge for any journalist.

“The violence in Mexico made reporters war correspondents in our own land,” Mexican journalist Marcela Turati once said, regarding the coverage of violence unleashed by drug cartels and security forces that persecute journalists in Mexico.

Whether in Mexico or Ecuador, as in Colombia, Honduras or Nicaragua, the coverage of violence has posed new challenges for journalists, because the traditional concept of armed conflict is being challenged in the region. The diversity of armed groups also means broadening the definition of the term. It is not just regular security forces, such as armies or police, and paramilitary groups such as guerrillas, but it can also involve drug traffickers, gang members or private security forces.

The Security Guide from the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ), perhaps the most complete document of security recommendations for reporters and editors, points out that "historically, security training courses have not specialized in addressing non-military contingencies, such as mitigating the risk of sexual assault while on assignment or lessening the hazards of covering organized crime.”

On many occasions, for journalists used to reporting on criminal activities, the work can turn into coverage of violent conflict at any moment.

On a daily basis, in their own cities, journalists run the risk of confronting armed groups or finding themselves in the middle of clashes with authorities or with each other. For a journalist from Nuevo Laredo, Tamaulipas, dodging the bullets of two cartels fighting each other is not much different than if he had been a war correspondent in Syria.

Or the case of the Ecuadorian journalists who traveled to a region of their own country to cover a wave of violence and suffered the fate that previously awaited war correspondents.

Jonathan Bock, director of the Press Freedom Foundation in Colombia (FLIP), describes a situation that occurs not only in his country, but in other parts of Latin America: the disdain of the authorities.

“There is a lack of State presence and then a narrative from the authorities saying that it is the fault of the journalists for being in areas where they should not be. There is no genuine interest from them in understanding the risks.”

Different types of violence

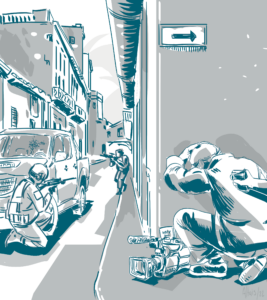

(Illustration: Pablo Pérez "Altais")

Covering a violent conflict means risks that, in today's Latin America, can present themselves in different ways.

One is that the journalist gets caught up in a confrontation between hostile groups and falls victim to crossfire. This is the traditional risk model of a journalist covering armed conflict. According to an analysis by Reporters Without Borders, 10 of 139 deaths of journalists between 2011 and 2020 in Latin America occurred during coverage in which the "journalist may not have been killed intentionally.”

This was the case of Brazilian journalist Gelson Domingos da Silva, who was shot to death while filming scenes from a police raid in a Rio de Janeiro favela in November 2011. Domingos was hit by bullets during a confrontation between police and suspects.

Although the percentage of cases in which journalists died while caught up in confrontations seems low, barely 7 percent of the total, the number is notable considering that the region is not home to traditional armed conflicts.

Violent conflicts have sometimes evolved in such a way that journalists have ceased to be respected observers of the parties to the conflict and have become a target of one of these parties.

Sometimes they become targets because one of the parties to the conflict does not want anyone to observe them, as happened in the Mexican state of Guerrero in January 2019, when a police officer pointed an assault rifle at 10 journalists who were covering an operation. Weeks later, police officers from Nezahualcóyotl, a municipality adjacent to Mexico City, attacked three photographers who were covering the discovery of a body on public roads.

On other occasions, they can become a bargaining chip for one of the armed groups.

They can do this to demand a certain kind of coverage from the media, as was the case of the newspaper El Siglo de Torreón in Mexico, where five employees were abducted for several hours by a drug cartel to pressure the newspaper to censor its coverage of violent acts such as murders and armed attacks in the city. The journalists were released with a warning to the newspaper's editors, who denounced the abduction and asked for protection. A group of the Federal Police set up surveillance outside the building and the agents were attacked on three consecutive days by the criminal group, putting the newspaper in the middle of a confrontation.

Journalists can also be used as a means of pressure to obtain concessions from a government, as was the case with the three Ecuadorians abducted by the FARC, who were trying to free three members who had been detained by the Ecuadorian government.

On other occasions, it is a question of using journalists, as was the case of Wilfer Moreno in Colombia, who in February 2020 received a call from a man identified by a pseudonym, who ordered him to suspend the broadcast of his newscast on CNC Noticias in Arauca during the 72 hours of the guerrilla armed strike announced by the National Liberation Army. Moreno refused and in response the anonymous subject warned him that he had one hour to leave the city because he would be declared a "military target."

Becoming a "target" is part of a new language adopted by armed groups ranging from guerrillas to drug cartels, who see journalists as one more party to the conflict, and one who, being defenseless, is more vulnerable.

In 2019, for example, judicial reporter Marcos Miranda was abducted by armed men in the state of Veracruz, Mexico, after receiving threats for his work on the Noticias a Tiempo portal. Miranda was abducted for one day in an intimidation attempt.

There are also cases of forced coverage, such as one reported by Bock about a photographer in the Arauca region, who was forced by a group from the FARC to take pictures of a police officer who had been abducted to deny rumors that the policeman was dead.

These are some examples that show the complexity of defining “violent conflict coverage” in Latin America today. The days of correspondents covering civil wars in Central America or confrontations with the guerrillas in Colombia have given way to confrontations between drug traffickers themselves, or drug traffickers with the military in Mexico; to incursions of armed gangs in neighborhoods of cities in Honduras or Brazil; to threats from police or attacks from private security guards.

Security measures

To the extent that groups have emerged that resort to arms to resolve conflicts or advance their interests, journalists in Latin America have found it necessary to adopt security measures to deal with unforeseen situations that may result in armed violence. For a reporter in Guadalajara, Rio de Janeiro or San Pedro Sula, it is impossible to know when a tour of a neighborhood or coverage of a police presence will end in a gunfight. In the same way that the Ecuadorian reporters who went to the border with Colombia to cover a wave of violence did not know that they themselves were going to become targets.

This has led many journalists to develop security protocols they must follow when covering situations ranging from a crime scene to a police operation, and from a simple trip to interview gang members in a neighborhood, to a military incursion into an urban or rural area.

(Illustration: Pablo Pérez "Altais")

However, there are distinctions between the types of journalists who do this type of coverage. In the case of Colombia, where there have been conflicts between security forces, armed groups and criminal gangs for decades, there is a difference between the journalists of a national outlet who cover the conflict in a region and the journalists who live and work in that same place.

“There is awareness of the risks when it comes to journalists from national media traveling to a region. They take safe transportation and other types of measures,” said Bock, from FLIP. “On the other hand,” he adds, “the situation of local journalists is dramatic, they are in dire conditions.”

But even in the case of journalists from media outlets with the resources to cover stories and take security measures, the risks materialize.

One of the most recent examples of conflicts that turned dangerous for journalists was on Colombia's border with Venezuela, where FARC groups are fighting with Venezuelan armed forces. In 2021, two journalists were detained by Venezuelan authorities when they were reporting for the channel NTN24.

Reporters and editors have had to learn to develop situational awareness to be alert to the dangers that may lie in wait and to be careful to plan their movements and routines knowing that at any moment they could find themselves in a crossfire. These protocols have been adopted by individuals, but have also been promoted by journalists in newsrooms, especially to get managers of media companies to invest in security training.

CPJ's Security Guide indicates that to compensate for the lack of security training for non-military scenarios, training models have been developed in the last decade that cover civilian scenarios and other aspects such as digital security.

"Hostile-environment and emergency-first-aid courses are prerequisites for safe reporting in any situation involving armed engagement,” the guide says, while also mentioning the importance of exercises on how to react in an abduction scenario.

In the following installments of this series on the safety of journalists in Latin America and the Caribbean, we delve into the coverage of violent conflicts in the region and the different forms it takes.

Although protection mechanisms exist or have been proposed in several countries to help journalists who may be in danger of being attacked by an armed group, we will analyze these tools in later chapters, because these mechanisms cover more risky situations, beyond armed conflict. Rather, we will focus on presenting various cases of attacks on journalists in this context and presenting recommendations for security measures that can be adopted, both individually and collectively in the newsrooms.

______

*This is the fourth report in a project on journalist safety in Latin America and the Caribbean. This LatAm Journalism Review project is funded by UNESCO's Global Media Defense Fund.

Read the rest of the articles in this project at this link.