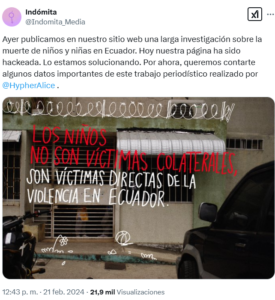

In February last year, the independent news website Indómita published an investigation that found more than a third of people who died violently in Ecuador were children under the age of 5. The headline read: “Children are not collateral victims, they are direct victims of Ecuador’s violence.”

The following morning, Indómita’s website was hacked, and journalists at the Guayaquil-based outlet were forced to adopt new measures to protect their digital security.

Journalists elsewhere across Latin America have also been the targets of digital attacks. In Mexico, a database of reporters attending conferences of former president Andres Manyel Lopez Obrador circulated in a leak forum. And in Venezuela almost 49 outlets, including El Político, Impacto and La Gran Aldea remain blocked by the country 's internet providers.

These incidents are part of a broader pattern of attacks on the press in the region. Between 2023 and 2024, more than 400 attacks, including hacking, censorship, espionage, and disinformation campaigns, were documented in the report "In Focus: Security and Main Digital Threats in Latin America."

The study, led by the organization Derechos Digitales in collaboration with the Latin American Observatory of Digital Threats (OLAD for its initials in Spanish), warns about the growing use of digital strategies to intimidate, silence, and obstruct journalistic work in the region. This is OLAD’s first joint report, an alliance of organizations working to defend human rights online. Among its findings, it reveals how governments, criminal actors, and organized groups have turned the digital ecosystem into a hostile terrain for journalism, activism, and civil society.

Cover of Derechos Digitales report "In Focus: Security and Main Digital Threats in Latin America." (Photo: Screenshot)

“Understanding the digital threats in the region is important so we can react and take action,” Rafael Bonifaz, Leader of the Latin American Program for Digital Security and Resilience at Derechos Digitales and editor of the report, told the LatAm Journalism Review (LJR).

“It’s important to take a moment, analyze what happened, and gain a deeper understanding of what’s happening to us,” he added. “Usually, there’s a scandal every week; we’re horrified, and the next week there’s another scandal, and we forget about the previous one.”

OLAD includes Fundación InternetBolivia.org from Bolivia, Escola de Ativismo, Instituto Nupef, and MariaLab from Brazil, Colnodo and Fundación Karisma from Colombia, LaLibre.net Tecnologías Comunitarias and Taller de Comunicación Mujer from Ecuador, Social TIC and Sursiendo from Mexico, Conexión Segura from Venezuela, and Código Sur, Derechos Digitales, and Fundación Acceso, which have regional reach.

The report is available in Spanish, English, and Portuguese.

According to the report, disinformation is a widespread phenomenon throughout the region and represents one of the biggest challenges in the digital ecosystem.

The report highlights cases of disinformation in rural communities in Bolivia, Peru, and El Salvador. In particular, it focuses on Bolivia, where three Indigenous localities (Villa Tunari, Cochabamba; Yacapaní and Montero, Santa Cruz), centers of political parties with ongoing tensions, experienced censorship and violence due to misinformation distributed through social media.

The document also highlights legislative proposals in Colombia and Brazil that seek to make news content subject to payment by the platforms where it’s shared and to regulate the indiscriminate use of artificial intelligence, which facilitates the creation of false information.

Wiretaps are also a recurring pattern across Latin America. The report mentions two emblematic cases that, although they didn’t occur within the analyzed period, did see updates. First, the illegal interception using Pegasus software on the phone of Mexican journalist Carmen Aristegui. In early 2024, a federal judge declared the only defendant in the espionage case innocent.

Second, the legal battle against NSO, the manufacturer of the Pegasus spyware, by journalists from El Faro in El Salvador whose communications were intercepted. In mid-2024, tech giants Microsoft and Google filed letters of support for the case in a California court.

“The biggest digital threats to journalism in Latin America are, on one hand, disinformation and censorship. On the other, the direct attack on journalists to scare them into stopping their work or disrupting their investigations,” Bonifaz said.

Juan Manuel Casanueva, executive director of Social TIC in Mexico, one of the organizations that collaborated on the report, agreed. For him, one of the biggest digital threats to journalism today is “the ecosystems with relevant disinformation agents like Elon Musk on X or other government representatives and ideological groups.”

In February 2024, Indómita’s website was hacked, and journalists at the Guayaquil-based outlet were forced to adopt new measures to protect their digital security. (Photo: Indómita post on X)

The report concludes that the main threatening actors are governments, anti-rights groups that threaten online freedom of expression, criminal actors with a presence in cyberspace, and individuals expressing sexism and racism.

However, the report’s creators couldn’t obtain comparisons and patterns due to the nature of the data from each collaborating organization. For example, only three organizations manage direct helplines and offer support and response in cases of digital gender violence. Therefore, there’s an underreporting of cases in this area.

From December 2023 to March 2024, Indómita Media received more than 300 malware infections on its website. The attacks once left them offline for up to two weeks.

“Now journalists in Ecuador are increasingly exposed to attacks ranging from the simplest, like self-censorship and information blockages, to more serious cases like digital threats,” Thalíe Ponce, director and founder of Indómita Media, told LJR.

LaLibre.net, a collaborating organization of the report, provided Indómita Media with a new server and a stronger and more accessible technological infrastructure. This also facilitates smoother communication with experts in the event of new attacks.

“An important lesson we learned was not to underestimate these types of attacks,” Ponce said. “Also, it’s important to have constant communication with civil society organizations. They have been facing situations that perhaps journalism, at least in Ecuador, hadn’t faced so directly until recent years.”