At 100 years of age, celebrated on Monday, Jan. 11, Brazilian journalist Hélio Fernandes still writes every day, whether on social media or on the blog he has kept since the closing of the newspaper he ran for 46 years, from 1962 to 2008.

To mark a century of life, and more than 80 years of journalism, the documentary "Confinado" (Confined) has been released. The film reconstructs one of the most significant moments of his career: the persecution he suffered during the military regime that ruled Brazil from 1964 to 1985.

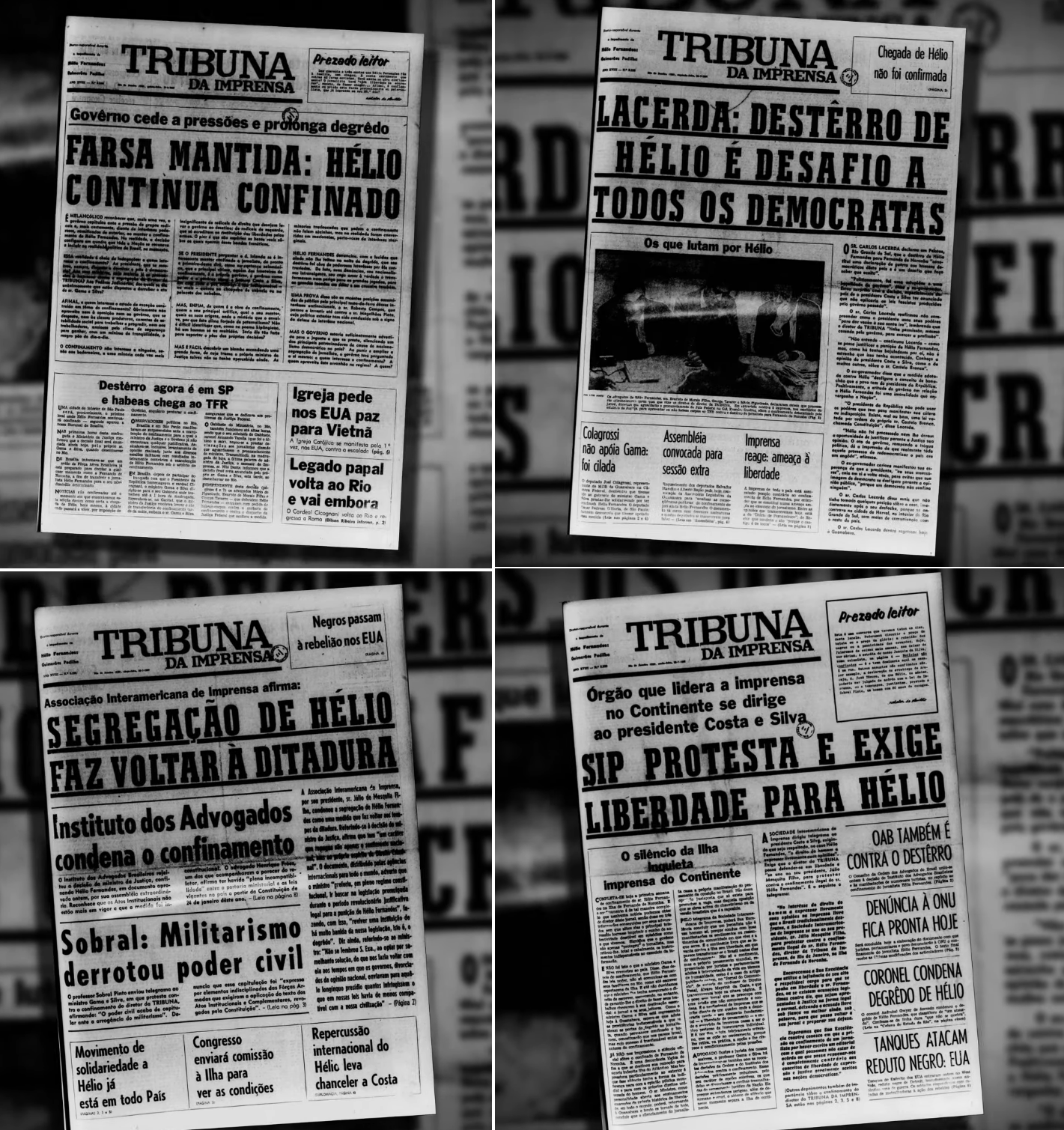

As the owner of newspaper Tribuna da Imprensa in Rio de Janeiro, Fernandes was one of the most critical, and therefore courageous, voices against the military regime. This earned him 37 arrests and detentions in which he was interrogated. As the regime faded away, his newspaper and his home were the target of bombings.

“Since my first contact with Hélio, in 2016, I was impressed by his energy in telling his stories and his prodigious memory,” journalist Mario Rezende, who directed the documentary, told LatAm Journalism Review (LJR). "Everything was always accompanied by details, such as dates and names of the people involved."

Mario Rezende talks to Hélio Fernandes during the production of ‘Confinado.’ (Courtesy)

“Confinado” tells the story of Fernandes' first compulsory removal from Tribuna da Imprensa, when he was sent without formal charge or prosecution to Fernando de Noronha, an archipelago in the Brazilian territorial sea, about 1500 miles from Rio de Janeiro.

The reason? In 1967, after Humberto Castelo Branco, first general-president of the period, died in an air accident, Fernandes published a harsh article in which he said that “with the death of Castelo Branco, humanity lost little.”

“One night I was having dinner in Rio de Janeiro when Colonel [Jarbas] Passarinho, who was in the same restaurant, got up and came to talk to me: ‘Journalist, they talked a lot in the barracks about murdering you. I thought Fernando de Noronha was so far away that no one would be able to kill you there. I came up with the idea,” Fernandes recalled in a recorded statement for the documentary, granted when he was 98 years old.

The regime believed that Fernandes' isolation would lessen the combativeness of his newspaper. However, on the contrary, Tribuna da Imprensa reported every day the arbitrariness of the situation: there was no formal charge or prosecution against the journalist. The military then decided to transfer him to Pirassununga. The inland city of São Paulo was only 372 miles from Rio and had no more than 30,000 inhabitants at the time.

The dictatorship wanted to reduce criticism from Tribuna, but failed

As an official “guest” of the Army, and not a prisoner, Fernandes was kept in a hotel and was allowed to move within the city limits, always accompanied by a plainclothes soldier. The film tells how the presence of an illustrious figure stirred up the city to that point that everyone wanted to meet the journalist:

Tribuna da Imprensa’s campaign against Fernandes’ confinement: military failed to silence the newspaper. (Reproduction)

“He was treated like a celebrity. There is even a story that I couldn't include in the documentary that he was even invited to take the kickoff at the start of a football game. So he was really [treated like] a celebrity, contrary to what the military certainly expected,” Rezende said.

“When they released me, they gave me various guidelines. I couldn't run a newspaper anymore. I could no longer write under the name Hélio Fernandes. Then I started to sign under the name João da Silva, which was the name of a soldier who died in Italy, from FEB (Brazilian Expeditionary Force). And they knew it was me,” Fernandes said in the documentary.

Hélio Fernandes ran the newspaper Tribuna da Imprensa from 1962 to 2008. (National Archives)

Then he would spend another period of confinement, this time in Campo Grande, in Mato Grosso do Sul. And his newspaper would spend more than ten years with military censors within the newsroom. When the military regime was coming to an end, Tribuna da Imprensa and the journalist's residence were the targets of bombings.

"It's a risk you take when you decide to stay in the trench fighting," Fernandes said. “The only way to make the newspaper not work was to destroy the machines. My feeling was that I was really annoying the dictatorship. Alone, I was annoying the dictatorship.”

Fernandes was reluctant to give an interview for the documentary about himself. The process of convincing him took time and Rezende believes that it was only successful because he himself was born in Pirassununga - although he was only a child when Fernandes was confined there.

"I believe that he only accepted to receive me at his home, after much insistence on my part, because I was born in Pirassununga and knew many people who lived with him during his confinement," Rezende said.

At 100-years-old, Fernandes writes daily on his blog and Facebook profile. (Courtesy)

Today, at 100, Fernandes still writes daily on the internet. His newspaper, Tribuna da Imprensa, stopped circulating in 2008 due to debt and lack of financial resources. Since then, Fernandes has kept a blog and later created a profile on social networks, where he posts comments and analyzes national politics.

In one of the last posts of 2020, before going on a brief break, he promised his readers:

“In 2021, we will be attentive to events and publishing, connected according to the famous phrases of my dear brother Millôr [Fernandes]: 'Computer, do your work' and 'If the reporter receives confidential information and does not publish, it is better to open a supermarket.’”

The documentary “Confinado” is available on YouTube in Portuguese.