Eleven-year old Juan Alliaume Irurueta is a voracious reader and loves video games. For three years, he has published reviews and interviews about his interests for Gigantes, a Uruguayan monthly print newspaper aimed at children and pre-teens that is a big success with audiences.

Cover of the June 2023 edition of Gigantes, which focused on adolescence (Courtesy)

“They published my first video game review in the fourth edition,” Alliaume told LatAm Journalism Review (LJR). “I read somewhere that you could participate, and that's good, I said, why don't I?"

In his collaborations with Gigantes, Alliaume has interviewed Roy Berocay, the country's leading children's book writer, and movie director José Pedro Charlo, in addition to reviewing books ranging from “Harry Potter and the Cursed Child” to “Ernesto, the exterminator of monstrous beings and other things.” He is one of dozens of children and pre-teens who have collaborated or regularly collaborate with the publication, which comes out as a 32-page full-color tabloid each month.

As traditional newspapers around the world have cut their publications aimed at children, independent newspaper la diaria launched Gigantes and gained more than 2,000 paid subscribers in three years.

Gigantes is not sold on newsstands and depends solely on subscribers at 330 pesos (about US $8) per month.

The secret to its success, according to its director Martín Otheguy, is incorporating young readers into the production process and addressing what really interests them.

At the heart of the proposal is to avoid being condescending, considering children and adolescents as people who think critically and have genuine tastes. Gigantes aims to speak directly to them, balancing information and entertainment, Otheguy told LJR.

“You always have to think about whether what you produce is of interest to children and ask them directly. Incorporating their opinion is essential,,” Otheguy said.

Innovating from the beginning

Gigantes incorporates several innovative practices from its parent publication, la diaria. Founded in 2006, the Uruguayan newspaper is an innovative case in Latin American media due, in part, to its management by a worker cooperative, its investment in digital subscriptions and expansion of verticals.

Its strategy is to create a community around knowledge, involving subscribers in projects and discussions. It currently has more than 22,000 subscribers and around 320,000 people registered on its website – that’s almost 10% of the Uruguayan population.

Just as la diaria does with other products, Gigantes started with a survey sent to its reader base to see if there was a public need for a product for kids, said Damián Osta, co-founder and manager of la diaria.

“We saw in the pandemic that the situation of children was invisible,” Osta told LJR. “We then sent a survey to our subscribers and to those registered in our community, and 7,000 people responded. We asked about their opinion about media that covered childhood.”

A report from the June 2023 edition of Gigantes that illustrates the different bodily changes a child goes through during adolescence. (Courtesy)

The survey found, for example, that 54% of those consulted strongly agreed with the statement that "the view of girls, boys and teenagers is made invisible by a large part of society, and, in particular, by media.” Fifty-three percent said there wasn’t enough information for children in the country.

They also asked if people were willing to participate in a group activity to improve the project and almost 40% said they would participate.

To test out potential collaboration, they held a virtual event with children and teenagers and asked about their experiences with the pandemic.

“This was a playful exercise and a minimum viable product. It helped us test the idea,” Osta said.

Then they returned to the participants for more feedback. Tests, consultations, adaptations and new tests are recurring practices.

According to Osta, Gigantes, which has no advertising, is breaking even financially. To diversify their sources of income, they invest in events and are preparing to hold a festival next year that would feature games and other attractions.

Otheguy said the team is in contact with publishers and plans to launch books with the Gigantes label by the end of the year or the beginning of next year. He added that they also plan to reinforce their online presence in the near future and to launch an audiovisual channel.

Balancing information and entertainment

Otheguy admits that the sections that are most successful are not journalistic, such as features or interviews. Instead, games come first, then book and game recommendations from other kids, and then comics.

A comic featured in the March 2024 edition of Gigantes (Courtesy)

The director said the newspaper's “big dilemma” is being able to balance information and entertainment.

“In fact, sometimes they tell us, for example, 'we want more games, we want other things.’ It's a balance, sometimes you have to put things more linked to leisure and others that are not so entertaining," Otheguy said.

In this balance, economic factors also come into play: sometimes, writing a feature is more viable when there is no way to publish more illustrations due to lack of budget. The editions are richly illustrated, under the command of art director Sabrina Pérez. The “giants” from the newspaper’s name are anonymous creatures of various colors, which appear throughout the editions.

Despite entertainment, there is space for journalism, generally done by professionals. Often, however, it also comes from children who want to talk about what they experience and find interesting.

"The articles are not the most remembered, but we realized that there are some children who do read them and we continue doing them,” Otheguy said. “It does happen, however, that many of them want to participate in some way so they send us ideas, for example, to publish articles about their band, about their school, and many times we do them. So, as protagonists, they like to appear and then see themselves in those photos.”

Alongside these articles on milder subjects, there is space to deal with more delicate topics. Gigantes published, for example, a short feature on how children were living through the war in Ukraine. Parents of young readers can be fearful of these kinds of subjects, Otheguy said.

"We have discovered that there are some complex issues, which even make a bit of noise. It is also difficult for any publication to tell you the situation of a war in a half-page article, to express it like this with all the complexities it has. But always trying to show children the reality of children from other parts of the world," he said.

Other ways of participating

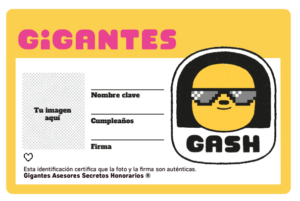

In addition to collaborating with articles and drawings, children contribute to Gigantes in several other ways. First, there is a mailing list called GASH (Honorary Secret Advisory Giants, for its acronym in Spanish), which currently has between 70 and 100 members, but is open to all children who want to participate. Every two or three weeks, the editorial team sends topic proposals and collects responses from readers.

License for the members of the GASH - Honorary Secret Advisory Giants, a special mailing list open to all readers of Gigantes. (Courtesy)

There’s also a private virtual space that functions as a moderated forum where readers can create an avatar and a nickname.

Finally, the Gigantes team also holds meetings to gather feedback on specific projects. These meetings end up functioning as focus groups for their audience.

“We don't do them as regularly as we would like, but we do them every few months when we need to share ideas with them and know what they think,” Otheguy said. “To create our new website, we had two meetings with them at la diaria. We shared a snack and we asked them to tell us what things they would like to see on a website, and we made a form where they left ideas.”

Awards and other honors

At the end of last year, the team also promoted the first edition of the Gigantes da Língua literary competition, with three categories: journalism, literature and scientific dissemination.

Alliaume was the winner of the journalism category, for his interview with filmmaker José Pedro Charlo about the documentary “Gurisitos: un año en el Paso de la Boyada.”

The jury said, “Juan demonstrates journalistic skill, a lot of freshness and also maturity to convey interest in both the filmmaker's work and the reality of the boys and girls who star in the documentary.”

Alliaume said the ideas for his collaborations with Gigantes comes from things he sees and appreciates.

“I see a book that I really like or I read it and I say that I have to do a review. Yes, that's it,” he said.

Otheguy says that the editing process is usually very simple, and that some of the collaborations “would be the envy of adults.”

“Of the most frequent collaborating children, very little actually changed. I would say that I have to edit the adult contributions more, not because they are poorly written, but because they are not used to writing for children. I just received two reviews of animated shorts done by a young girl and a teenager, for example, and they are very good. We try not to change the style, but we do try to understand what they wanted to say,” he said.

Javier Alliaume Molfino, Juan’s father, admires the newspaper.

“Gigantes is a publication that, at least in the Uruguayan context, has been making a giant difference,” he told LJR. “It really respects the intelligence of children.”

“Here, on the other hand, there is a publication that takes them into account, that publishes things that are really culturally relevant for the children and that touches on issues and raises them in very interesting ways,” he added.

His son agrees. As he had read a lot before, the reviews allowed him to share his knowledge with the world. Like so many journalists, however, his favorite moment is when a new edition arrives and he sees that his text has appeared on paper.

Regarding what topic he would like to talk about in the future, Juan already has a suggestion.

“It must be said that many of my generation believe in the robot apocalypse,” he said. “It is important to talk about it.”