Anna Virginia Balloussier's path is distinctive. In her youth, a typical hipster from Rio de Janeiro living in São Paulo, the journalist, who’s now 37, specializes in covering religion with a special focus on churches and evangelical believers.

The interest began somewhat by chance, as a task assigned to a Folha de S.Paulo rookie reporter, and matured until it provided her with a comprehensive view of Christian groups. Balloussier, who still works at Folha, currently as a special reporter, has sources ranging from very politically influential conservative pastors such as Silas Malafaia to leaders of small neighborhood churches and progressive religious people.

Her reporting follows the growth of evangelicals in Brazil. According to all opinion polls, the percentage of the population that says it follows the evangelical faith in the largest Catholic country in the world is constantly increasing. In 2020, a Datafolha survey found that they then made up 31% of the population, and the IBGE estimated in the same year that by 2032 evangelicals should surpass Catholics in number.

Balloussier's more than 13 years covering the topic recently motivated her to write and publish the book “O púlpito: Fé, poder e o Brasil dos evangélicos” (The Pulpit: Faith, Power and the Brazil of Evangelicals). This is her second book, after “Talvez ela não precise de mim” (Perhaps she doesn’t need me), a 2020 work about the experience of motherhood and the postpartum period during the pandemic.

In the new book, Balloussier discusses topics such as entrepreneurship, politics, tithing, abortion and sex among evangelicals, seeking, as she says in the introduction, to avoid “falling into the trap of reducing individuals to stereotypes.” Instead, she expresses the ambition to describe a highly heterogeneous religious following, which concerns significant changes in Brazilian society and politics.

Brazilian journalist Anna Virginia Balloussier, author of "O Púlpito", a recently released book about evangelicals in Brazil (Photo: Marcus Leoni)

LatAm Journalism Review (LJR) met with Balloussier in a café in São Paulo at the end of May for a conversation about the book, her work, her own faith, the characteristic irony in her writing style and the criticism she sometimes receives. The result of the conversation is below.

The interview has been edited for clarity and length.

LJR: Since 2010, you have covered religions with a special focus on evangelicals. How did this start?

Anna Virginia Balloussier: As I say in the book, I studied at a Methodist school and had evangelical relatives. Even so, I had no idea what this phenomenon actually was. In 2010, after leaving the Folha Training Program, my then-editor Vera Magalhães put me on a typical mission for rookie reporters: visit as many evangelical services and Catholic masses as possible to find out what was being discussed about abortion. That was the first election in which abortion came to the fore in Brazil in a relevant way. In one month, I went to more than 50 services and masses. I started to realize that there was something big going on and no one was paying much attention. On the one hand, it was genuine curiosity; As a child, I was interested in religions, my favorite book at age 8 was called "The Book of Religions.” But it was also a sense of opportunity and a gut feeling as a journalist.

LJR: What did you notice about the coverage and want to do differently?

AVB: The articles I saw used to come out in the Metro or Daily section with a tone reserved for the police beat; for example, complaints against pastors who financially abused believers. And I thought there was a broader phenomenon. Today, part of the coverage has migrated to the Politics section, for example. There is currently a lot of interest with these kinds of articles, which are very popular among editors. They fight for this type of news, which can appear in Economy, in Politics, in Metro.

LJR: What was the transition like to specialize in this?

AVB: After the election was over, I took over the coverage. After the season as a rookie focusing on Politics, I went to the Folha Teen section, for teenagers. And then, for example, I suggested going to the Catholic camp of Canção Nova, a charismatic movement, and I spent three days camping with them. I continued proposing stories: in 2011, it was the 100th anniversary of the Assembly of God in Brazil. This way I accumulated sources and some knowledge. Today I realize that I made a lot of mistakes back then.

LJR: How important is coverage with a specific focus on religions?

AVB: In Brazil, where religiosity is very present — there are surveys that indicate that 9 out of 10 Brazilians believe in God — this infiltrates various social pores. Among evangelicals themselves, there is a theology called the Seven Mountain Mandate, which speaks of the mission of occupying seven social spheres: education, entertainment, politics, family, among others. So, a religion is not an isolated identity, but something that will influence voting, children's schooling, and the education of future citizens. This makes this coverage essential.

LJR: How do you define yourself religiously?

AVB: Generally, I didn't talk publicly about this, but now it's been said in the book. I'm Umbandista [a follower of the Afro-Brazilian religion Umbanda] — or rather, I come from an Umbanda family and my whole family is. My mother is a medium; She doesn't work, but used to receive entities at home. So, I had a very intimate relationship [with Umbanda]. Not a classic institutional religious relationship, but an almost friendly relationship that I had with Juquinha, who was an erê [a playful spiritual entity associated with childhood].

LJR: Was there any kind of friction because of this at any point?

AVB: Never, but it was never widespread information either. Especially because I'm a journalist, so journalistic interest in me as a story only emerged now, or in my previous book, about motherhood. But many times I am covering a story in an evangelical church and there is an attempt at conversion. Or they ask me if I'm a Christian; and then I feel comfortable answering yes, because the Umbanda line that I follow believes in Christ.

LJR: What is your intention with this book, and which audience do you want to reach?

AVB: From the beginning, my idea was to write a clear, direct book in accessible journalistic language. I had two intentions: one was to be honest with my journalistic production and try to understand what that was, in retrospect. The other, that people outside the evangelical segment tried to understand a little more what it is. I know that pastors and evangelicals are responding well to the book overall. But I thought the greatest reach would be among the non-evangelical public, perhaps linked to the progressive segment, who were very prejudiced and didn't understand what it was about.

LJR: At the beginning of the book, you say you want to distance yourself from an "anthropologizing" approach. What would that be, and how does your approach differ?

AVB: I don't think the problem is a vision that uses sociology or anthropology, so much so that I cite several scholars. But I didn't want to just stop at that. Because journalism, sometimes, when talking about a mass phenomenon, approaches it as if it were animals in a zoo. In a newsroom, there are almost no evangelicals.

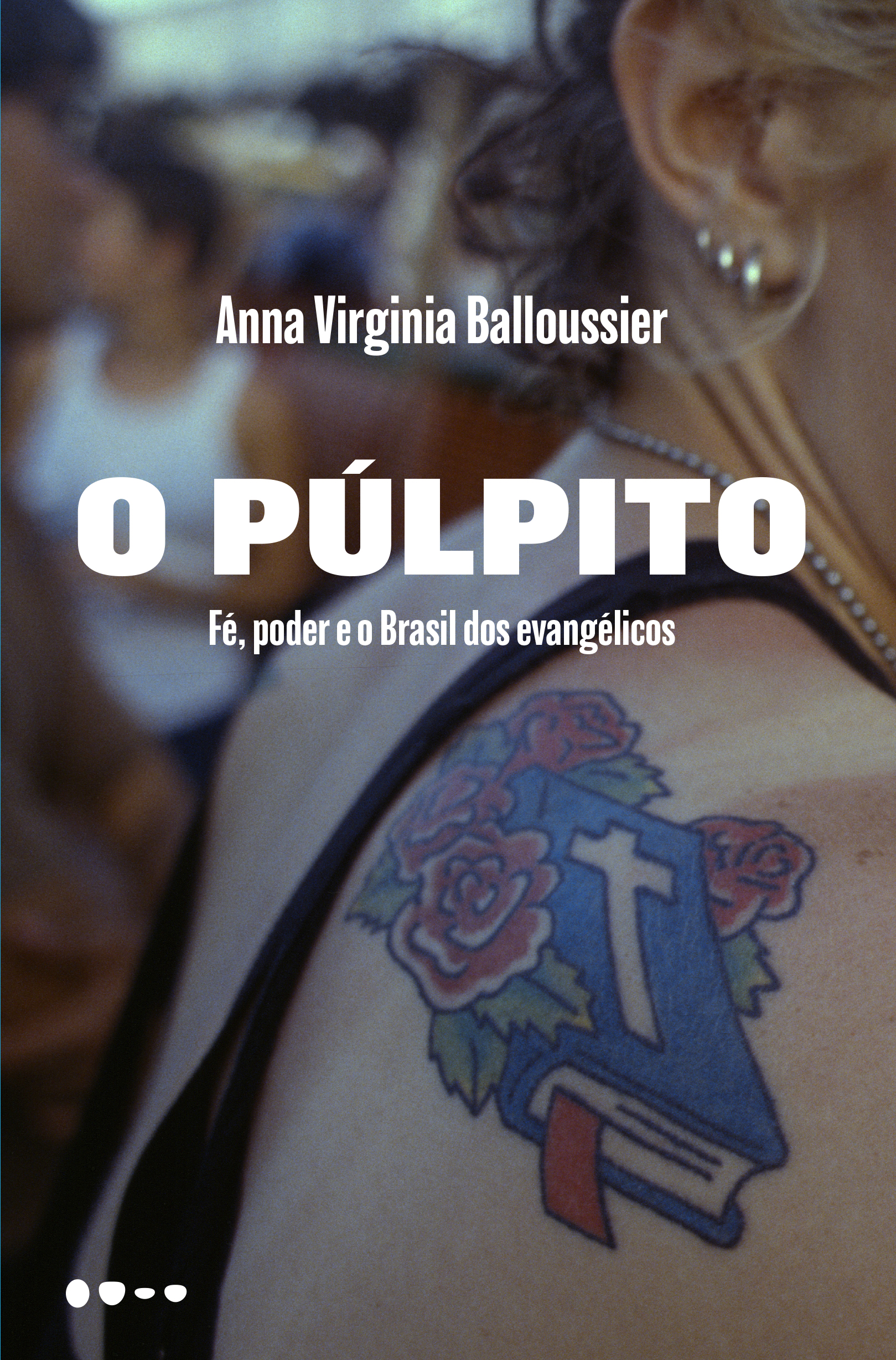

The cover of "O Púlpito" (The Pulpit), by Brazilian journalist Anna Virginia Balloussier

LJR: How did you think about the structure of the book? There are first a series of themes separated into chapters, such as sexuality, abortion, entrepreneurship and politics. The penultimate one discusses the issue of power, and in my opinion it is more analytical than the others. How did this organization come about?

AVB: Basically, there was a dose of freestyle. From the beginning, I knew that I wanted to take a character as the thread of the chapter to introduce the reader to the story in the most illustrative way possible, and then try to understand. While talking about sexuality, I realized that abortion deserved a separate chapter. Tithing, the last chapter, is an issue that always raises a lot of controversy and doubts, and also deserved a separate chapter. Interestingly, the chapter you mentioned, Power, was the last to appear. At the time, my editor came and said that he felt the need for one more chapter that would close the story; He thought I was saying a lot about how evangelicals are in society, but there was a part missing that explained what they want with this, why they want this power. Then came the idea for this chapter, to talk about how evangelicals see themselves in this project of nation, in the project of what it means to be a citizen.

LJR: From an early age, your style had a very clear ironic trademark. In your first text in "Religiosamente,” the blog about religion you kept for a few years, when mentioning different faiths, you speak of "a worshiper of bacon toasted in butter.” How do you balance that with coverage of religion?

AVB: For better or for worse, I've always used metaphors a lot. I've even reduced that a little, but I've always had a text that people recognized and said "it's yours.” By covering religious sentiments, I adapted it into a more respectful way, so to speak. Evangelicals were never mad at me. My idea was always to laugh with them and never at them. So I adopt a respectful tone, but knowing in advance that the evangelical is not a formal being and that they do laugh at themselves. There are a multitude of blogs and memes and evangelical profiles on social media making fun of themselves. I use less irony when I know it will upset the person, but what is perhaps more important for me is to be illustrative, to try to make people see the scene, what I am seeing and feeling.

LJR: You often criticize progressive sectors for allegedly not understanding the religious part of the population. How do you believe this alienation occurs?

AVB: There is the idea that I only criticize a sector of the left that doesn't care about evangelicals or looks at them with prejudice. This is not the truth: most of my articles end up being critical of the evangelical leadership, which tends to be much more conservative and much more to the right than the evangelical base itself. Coverage is critical of them. But, among progressives, what stands out is this other approach [critical of the left]. Now the left didn’t lose the [2022 presidential] election by a whisker; among evangelicals, it was massacred. The projection gives almost 70% of the evangelical votes to the conservatives. Now, the left has won this electorate in the past, it had the majority of votes. And, if it doesn't understand what is happening, soon the distance between this left and the evangelicals will become abysmal, it will no longer be able to be overcome. Remembering that the evangelical electorate is only growing.

LJR: And what does this misunderstanding consist of?

AVB: On the one hand, they believe that there is no autonomy in the evangelical faith, in the evangelical base. Some progressive sectors think that the evangelical base or the evangelical faithful is always a poor wretch who is under the control of an unscrupulous pastor. A person has much more autonomy than one might imagine, although obviously abuses occur and it is always necessary to report them. Now, journalistically speaking, I have already faced many charges... You cannot reproduce a quote from an evangelical leader that causes distortions or fake news just by declaring it. It is necessary to contextualize it or deny it, and I always try to do that.

LJR: What types of charges do you think you’ve received, and how do you understand them?

AVB: For example, people ask me why I talk so much to Silas Malafaia, the pastor who appears most in Brazilian media when there are so many progressive and left-wing evangelical leaders. But Silas Malafaia was a pastor who had direct access to [Jair Bolsonaro's] ear as president. And, furthermore, anyone who understands the evangelical segment knows that his reach is much more transversal. He has been a televangelist for over four decades, and is also very active on social media. So he is a compass for small pastors who make up the majority of the evangelical segment.

But, above all, there is an attachment to the progressive field of progressive pastors such as Congressman Henrique Vieira, who is an evangelical pastor and who has a beautiful theology, but is actually more progressive than many progressives I know. He is completely out of the curve and his reach in the evangelical segment is minimal. The truth is that Brazilian journalism gives disproportionate space to progressive pastors, because they do not represent the evangelical base. It's much more wishful thinking than reality. The reality is not just Silas Malafaia. But the disproportionality often lies in the space given to progressives. Because the Brazilian media, in terms of customs, is much more progressive and liberal. I have much more journalistic interest in understanding what the evangelical base is than in directing it towards what I want it to be.

LJR: Before the 2018 elections, when Jair Bolsonaro was elected, you covered a lot of the far right. Was it a similar interest that moved you?

AVB: In 2017, I accompanied Bolsonaro on a trip to Rio Grande do Norte, which is an electoral field where the Workers’ Party [PT for its acronym in Portuguese] is very strong. And, when I went there to look closely, I saw that those who were there were often young people who had never voted in an election or had voted once and for Dilma. And Bolsonaro was becoming this phenomenon, this myth. And there was this desire of mine to understand precisely those who don't think the way I think. It was a much bigger challenge, much stronger. One point that strengthened this was when I covered the 2016 American election as a correspondent and noticed the Donald Trump phenomenon growing. At the time, Clóvis Rossi [a Folha journalist who died in 2019] wrote that, if Trump won the primaries, he would have the momentum and win the election. So I went through the election thinking that Trump was going to win. I saw history repeating itself in Brazil, I saw a media that wasn't looking that way, that was too enthusiastic about very restricted phenomena. Now, it seems obvious. The experience made me see that Bolsonarism was following the same path: a phenomenon that classical journalism did not reach. And joining evangelical churches helped me realize this.

LJR: A criticism that is often made of the press is that it normalizes positions that would be considered radical or extremist. I've seen this criticism directed at your work, specifically: that you're giving some people a megaphone. How do you view this criticism? And what is the role of journalism in this regard?

AVB: There is a real risk of normalizing certain discourse. Just think about American TV — this also happened in Brazil, in fact — showing Trump's speeches running wild without anyone contextualizing or refuting them. But I think the biggest risk is pretending that these voices don't exist. Maybe it's a somewhat outdated legacy from a time when it was this so-called big media that called the shots and all we had to do was not talk about something and it wouldn't happen. That doesn't happen anymore. I remember The Huffington Post before the primaries saying they wouldn't cover Donald Trump and would cover him in the entertainment section because he was nothing more than a clown. At the end of 2015, when he was far ahead in the primaries, they changed their minds. Ignoring a phenomenon because you don't like it, or under the argument that you can expand it and give it a spotlight, is a risk of not understanding it and being overwhelmed by events.

LJR: How do you cover it then?

AVB: It's a minefield. You will study some formats: when it is appropriate to do an interview in the Q&A format, for example. Q&A is an interview that can be very complicated, because it doesn't allow you to reflect much on what the person says. You can't always contextualize it at the time, and then you can't later. But, again, the greater risk is to pretend that it doesn't exist than to put it on the newspaper page. I consider this view a little naive that, in 2024, it is the fact of being on Folha de S.Paulo or Jornal Nacional that will make things happen.