This story by Giovana Fleck originally appeared on Global Voices on June 4, 2021.

Journalists warn for a “homogeniety” and “exoctic” set of narratives to report on China. | Image: Giovana Fleck/Global Voices

“You can't understand China without being in China”, says the journalist Marcelo Ninio. He is the only Brazilian correspondent accredited on Chinese soil. In fact, the only South American. “There is also a Cuban reporter. But only the two of us from Latin America.”

But why so few journalists? Considering that China is Brazil's largest trading partner and so vast and multiple, it is plausible that it is in the public interest to report more about the country to Brazilians. “Do you want the short or the long answer?”, says Ninio, in a call with Global Voices.

The short answer is what is expected: money. He emphasizes that the high cost of placing a reporter in another country coupled with the lack of resources in many newsrooms has meant that one of the first areas to suffer budget cuts was international journalism.

But there is more complexity to this problem. For Ninio, it includes cultural issues and the difficulty of being a journalist in China, a country full of restrictions. “We need more information and good analysis about China, otherwise, we will continue to see disinformation and sinophobia growing in Brazil," he says. “This shrinks Brazilians possibilities of understanding the world."

A culture of stereotypes

“The reference from Asia to the Brazilian is something very homogeneous. It is common to hear that Chinese, Japanese, and Korean are all the same in Brazil,” says the journalist Talita Fernandes, in a call with Global Voices. After more than three years as a reporter for Folha de São Paulo newspaper, one of the main newspapers in Brazil, Fernandes decided to move to Beijing to dedicate herself to studying Chinese. “In the press, the image of China bears no fewer stereotypes; it is commonly quoted from the analogy of a ‘rabid dragon’, for example,” she says.

These clichés were also observed by Folha's columnist Tatiana Prazeres, who is a Senior Fellow at the University of International Business and Economics in Beijing. Prazeres published a column in February 2021 saying that, in Brazil, “there are passionate opinions, categorical positions and definitive views on China,” and there is a lack of information and analysis.

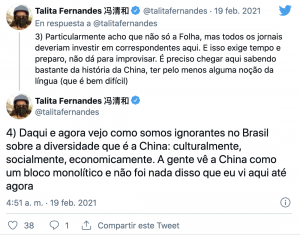

After Prazeres's column, Talita Fernandes went on Twitter to publish her own perspective about the lack of coverage about China:

“From here and now I see how ignorant we are in Brazil about the diversity that is China: culturally, socially, economically. We see China as a monolithic block and that’s not what I’ve seen here so far.”

In order not to be so distant from the journalistic practice, she decided to take on the editing of the Shūmiàn newsletter, a platform coordinated by volunteers that seek to establish bridges of understanding between China and Latin America. The fact that it is voluntary is also a protective measure. “If I were paid for it, I would be practicing an illegal activity since freelance journalism is something that doesn't exist in China,“ says Fernandes.

In her work, Fernandes explains that she tries to escape the narratives that she frequently follows in the Brazilian press. “The news outlets are very dependent on wire agencies or global newsrooms, which means that the coverage loses nuances and sometimes ends up being shallow or lacking a connection with Brazilians. Or, when the reporter wants to go deeper, he always ends up presenting China to the reader, in a repetitive tone that sometimes is too critical or too naive.”

Marcelo Ninio says that the community of international reporters in China is united. “We all go through the same difficulties, we created a support network to help each other as we can.”

For him, the coverage of his colleagues represents much of what is common to Western democracies but does not carry ideas that are central to Brazilians. “My challenge here is to make a coverage that escapes the tension between the West and China. There are fights that are not part of the international strategy of Brazil-China and vice versa.”

Ninio also says that the main thing, for him, is to analyze the environment around him and to understand Chinese perspectives without paternalism.

How the Chinese look at human rights is an example. For Brazilians, the concept of human rights is usually associated with freedom of expression, whereas for the Chinese, the discourse is more often about development. “Both things are complementary, but I know that I need to explain that for a Brazilian audience.”

This is Ninio's second turn as a correspondent in China. The first was between 2013 and 2015, also writing for Folha de São Paulo newspaper. An international journalist with experience in the United States, Europe, and conflict coverage, Ninio decided to present the idea of a column from the Chinese point of view, with a Brazilian perspective, to the newspaper O Globo.

“I arrived in China in October of 2020. Besides the pandemic, what became clear to me was that the difficulty to access information was much greater,” says Ninio.

He attributes this to the growing clashes with the Trump administration last year. Ninio explains that accessing official sources from the government is almost impossible, but now citizens are also more reluctant to express an opinion. Besides that, language is a barrier and he has to count on translators to help during interviews. “But all these barriers force us to create mechanisms to handle the work,” he says.

Ninio uses a combination of research and field reporting to cover China, since access to sources and official data is so limited. “To this day, I hear from Brazilians that China is to blame for the pandemic, that China wants to control the economy… Brazil needs reporters that will cover China addressing those gaps of information.”

“Invisible heroes”

The difficulties of covering China are not only shared among Brazilians. Talita Fernandes describes the Chinese citizens who work as assistants at international publications based in China as“invisible heroes”. They are the ones with local knowledge and sources but are hired without the “reporter” title and don't sign their own reporting. This happens because Chinese citizens cannot work as journalists in the country for foreign media outlets.

But this arrangement didn't stop Haze Fan, a news assistant for Bloomberg News, from being arrested in 2020. The accusations that led to her arrest were not made clear by the Beijing National Security Bureau. She remains in detention on suspicion of endangering national security.

In March of 2021, the BBC decided to transfer their Beijing correspondent to Taipei because of threats due to the coverage of the Uyghur people. The Foreign Correspondents’ Club of China claims that at least 20 reporters had to leave the country since 2020.

Such hostility is exactly what specialists advise as harmful to China’s image globally. Trying to address this gap, some independent journalistic initiatives like ChinaFile, Caixin Global, and Diálogo Chino (or its English version, China Dialogue) – in addition to the newsletter Shūmiàn itself – attempt at bridge China to the West. “We need diversity and competition to report on China to avoid false narratives like that of the ‘Chinese virus’ that became so popular in Brazil,” says Fernandes.

This story is part of a Civic Media Observatory investigation into competing narratives about China’s Belt and Road Initiative, and explores how societies and communities hold differing perceptions of potential benefits and harms of Chinese-led development. To learn more about this project and its methods, click here.