Journalists in Cuba have been the target of repression and harassment to prevent the exercise of their profession during 15-N, a series of demonstrations called for this Nov. 15 demanding the release of people imprisoned after the protests of July 11, as well as the end of the police repression.

Cuban authorities deployed police and military on a level rarely seen in Havana to deter protests, as reported by some journalists on social networks. Additionally, the Government of President Miguel Díaz-Canel declared that the demonstration was illegal and considered it a "destabilizing provocation.”

Among the methods of repression against journalists registered in the days prior to Nov. 15 are extrajudicial house arrests, summons with authorities, the suspension of services, the withdrawal of accreditations, the presence of security agents near the journalists' homes and some "acts of repudiation,” as the demonstrations in which supporters of the regime gather to physically and verbally attack activists or journalists are known.

Journalist Camila Acosta protested peacefully with applause at her home. (Photo: Facebook)

“Practically all independent journalists are besieged in our homes, some have had their telephone service and internet access cut off. The country has been totally militarized, that's what we have seen,” Camila Acosta, Cuban correspondent for the Spanish newspaper ABC, told LatAm Journalism Review (LJR).

Acosta has been unable to leave her home for more than four months after covering the July 11 demonstrations. The journalist was charged with "public disorder and instigation to commit a crime,” for which she could face from 3 months to a year in prison. For the time being, she remains under house arrest awaiting trial, although she has not had access to any investigation files.

However, dozens of journalists have been held in their homes since last weekend without any judicial order, closely watched by members of the National Revolutionary Police (PNR), some of them dressed in civilian clothes, according to the Cuban Institute for the Freedom of Expression and Press (ICLEP).

“There is no court order, they just put a patrol and sometimes several state security officers outside your house and when you get ready to leave they simply tell you that you cannot do it, they prevent you. And if you refuse, they arrest you,” Acosta explained.

Washington Post columnist and co-founder of the digital outlet El Estornudo, Abraham Jiménez Enoa, is in the same situation. On the morning of Sunday, Nov. 14, he reported on his social networks that Cuban state security agents remained outside his home and informed him that he was "under house arrest" and prevented him from going out into the street.

At noon on Monday, Jiménez Enoa posted that he was still under siege and his home was surrounded by even more plainclothes officers than the day before.

Likewise, journalist Luz Escobar, from digital newspaper 14yMedio, published Sunday night on her Facebook profile that a man in civilian clothes and a police officer were staying outside her house, and a patrol was at the corner of her building. Escobar published a video in which the non-uniformed person prevents her from leaving her house and orders her to stop recording and put down her cell phone.

Agents prevented 14yMedio journalist Luz Escobar from leaving her home in the days prior to 15-N. (Photo: Facebook)

Escobar had denounced two days earlier, on Nov. 12, that she had been summoned to the Minors' Agency of the Ministry of the Interior (MININT), where they informed her that they had seen her two youngest daughters playing outside "with the mask on incorrectly” and they warned her that she could not take the girls to the 15-N march, or she would be committing a crime. The journalist said that she interpreted the aforementioned as a siege and pressure not to cover the protests.

This type of intimidation was also suffered by the journalist from ADN Cuba Yadiris Luis Fuentes, who was summoned for questioning at the headquarters of the National Revolutionary Police on Friday, Nov. 12, according to the site. It was the second interrogation to which she was subjected in less than a month, after on Oct. 15 she was summoned and threatened with being prosecuted for the crime of “mercenarism.”

“The Cuban regime treats us as criminals, terrorists, a social scourge. That we report is a crime in the imaginary and convenient Penal Code that the dictatorship draws up and fixes every day," the journalist wrote on Twitter.

Journalist Orelvys Cabrera, from the site CubaNet, was also summoned by authorities on Friday, Nov. 12, to go to the State Security headquarters in Matanzas province, where he was held after the July 11 protests, according to the media outlet.

Days before, on Oct. 27, Cabrera had been called by the National Revolutionary Police for an “interview” in which he was questioned about his plans to cover the 15-N protest and in which they informed him that he was going to remain under surveillance 24 hours a day, CubaNet said.

“They basically summoned me to inform me that I will be watched by the head of the sector that corresponds to me. That I will have monitoring 24 hours a day and that they are going to do an investigation on my block to see what it can shed on my social behavior," the journalist told CubaNet.

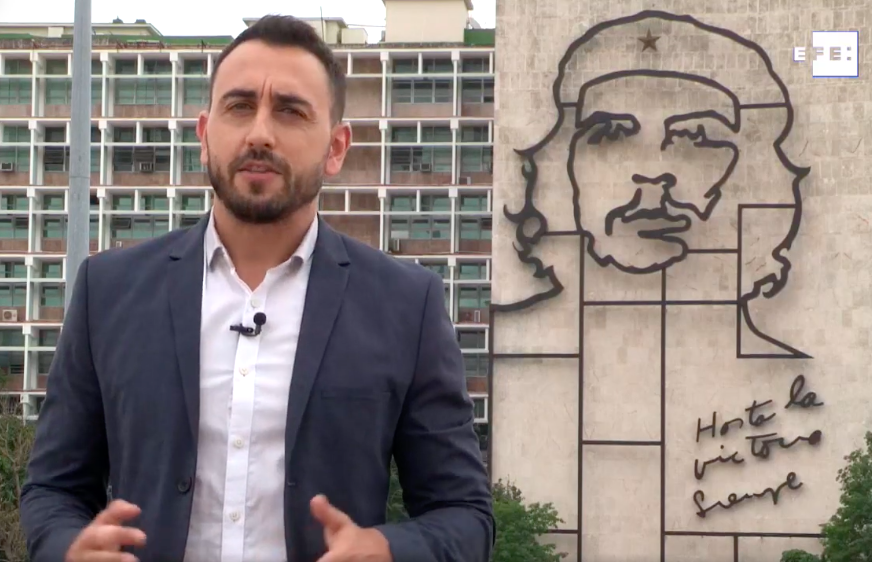

But not only Cuban journalists have been affected by repressive and censorship measures. The weekend before 15-N, accreditations were withdrawn from three reporters, a photographer and a cameraman from Spanish news agency EFE on the island.

Atahualpa Amerise is the coordinator of EFE in Cuba. His team suffered the withdrawal of his accreditations prior to the demonstrations. (Photo: Facebook)

Faced with international rejection and after a series of diplomatic efforts by the Spanish Embassy in Cuba, only two of the five journalists recovered their credentials.

“We continue without news, covering #15NCuba with an accredited journalist and camera from the six that make up the EFE team. We hope that they will reacredit us as soon as possible. If not, even at a minimum, we will do our best to tell you in detail everything that happens today,” Atahualpa Amerise, EFE's newsroom coordinator in Cuba, wrote Monday morning on his Twitter account.

The situation of the independent press in Cuba worsens

Since the July 11 protests in Cuba, in which several journalists were arrested and harassed for practicing their profession, and which attracted international attention to the situation on the island, the conditions for practicing journalism have become more difficult and dangerous, Acosta said.

“In the case of the independent press, we are not even recognized, we are constantly experiencing the entire repressive situation. After July 11 this has increased,” she added.

The detained journalists were eventually released with the payment of fines and after receiving "warning reports." However, Cuban journalists know that the constant threat of being arrested again weighs on them.

Acosta said she is the only independent journalist waiting to be tried on the charges against her while she remains under house arrest. The Spanish Government has been in talks with the Cuban Foreign Ministry to request her release, however it has not been granted.

“Right now the policy they are using against me is to keep me inside my house. It is the way they have to prevent me from the reporting work in the streets and this can be extended up to a year, without being subjected to trial," Acosta explained.

Even if the charges are eventually dropped, the journalist will have already spent several months denied freedom. However, the internet and social networks have helped Acosta continue to practice her profession from her home.

“I try to overcome all that, I try to work despite everything. And [I feel] proud because if these are the consequences of telling the truth, then I accept it proudly," she said. "I don't regret what I'm doing at all: keep going, keep reporting at least from home and don't lower my head."

This story was originally written in Spanish and translated by Teresa Mioli