Mexico is experiencing a silent epidemic of transfemicides that media are not reporting. That’s one conclusion reached by journalists Emma Landeros and Joel Aguirre after nearly two years of investigation documented in their book "Transfeminicidio."

In 2024 alone, 55 trans women were murdered, the highest number in three years, according to the organization Letra S. And so far in 2025, at least six transfemicides have been recorded, according to the National Observatory of Hate Crimes against LGBT People. The most recent killing was just two weeks ago.

“Transfemicide is a hate crime. And hate crimes in Mexico unfortunately receive little coverage, or are ignored, or are rendered invisible,” Aguirre, an editor at Newsweek en Español, told LatAm Journalism Review (LJR). “The media outlet that dares to cover it does so in such a shameful manner, so out of step with the tone required today, that it's downright vulgar. From that point on, we began to see that there was a problem.”

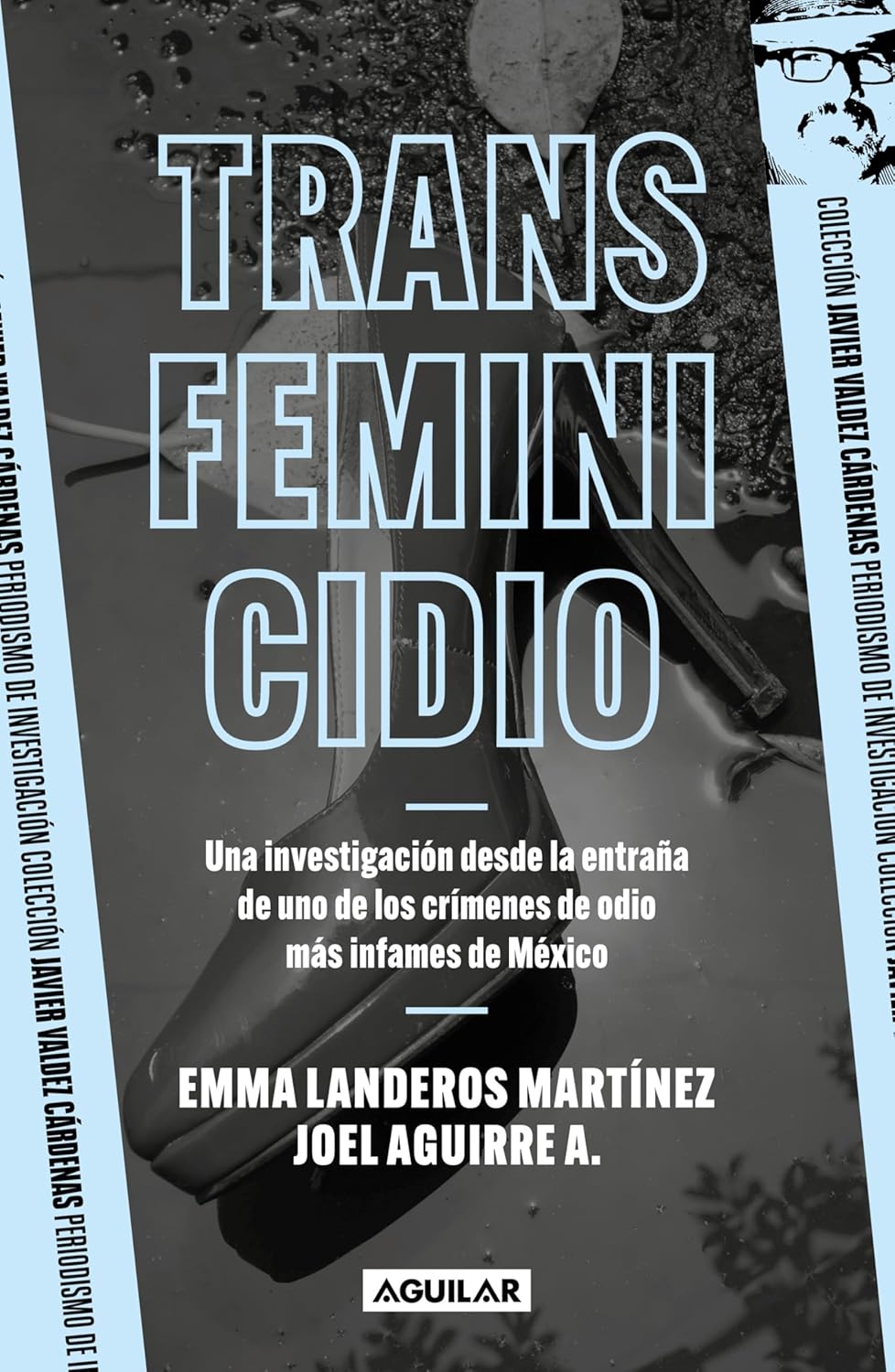

The book by Emma Landers and Joel Aguirre includes 12 stories that portray the brutality experienced by trans women in Mexico. (Photo: Edson Vázquez)

In their research, the authors found that in several Mexican states, news stories about murders of trans people were covered without considering the victim's gender identity, and with stigmatizing and revictimizing language. In some hyperlocal media outlets, for example, victims are still described as "men dressed as women," and pejorative adjectives and insults are even used, Aguirre said.

Their book, published in February 2025, includes 12 stories that portray the brutality experienced by trans women in Mexico through interviews with psychologists, lawyers, activists, survivors and victims' families. The book asserts that the hatred that motivates most of these crimes is related to a series of cultural factors, such as machismo and the prevailing patriarchy.

“From our journalistic perspective, we believe that this same trigger of machismo is what leads many media outlets and many sectors of society to make the issue of transfemicide and attacks on the human rights of transgender people invisible,” Aguirre said.

The authors' conclusions are consistent with the perceptions of researchers and organizations that advocate for LGBTIQ+ populations in Mexico.

Guadalajara-based trans and non-binary advocacy organization Impulso Trans has found that many media outlets cover the murders of trans women with a dehumanizing and sensationalist approach.

Mexican press coverage takes a heteronormative, stereotypical and prejudiced approach that contributes to the perpetuation of violence against trans people, rather than contextualizing the phenomenon as part of a structural problem, said Izack Zacarias, director of Impulso Trans.

“The way they're presenting it, we see that it contributes to continuing to blame the [trans] person from the start. They don't treat them appropriately, the person's [chosen] name and pronouns aren't respected,” Zacarias told LJR. “There are media outlets that try to do their best, but they're in the minority.”

He said this sensationalist approach encourages people to write hateful comments on news stories or on social media, which ultimately amplifies stigmatization and revictimization.

“I don't see [media] doing anything to stop the comments or block them or issue a statement to clarify that this isn't the case,” Zacarias said.

Landeros said that during their research for the book, the authors found numerous hateful comments on articles about murders of trans women, ranging from those that mock or treat the topic with irony to those that celebrate violence against this population.

When Landeros and Aguirre started researching their book, even finding basic statistics related to the murders of trans women in Mexico was an issue.

"Transfeminicidio" was published in February 2025. (Photo: Courtesy)

There are no official public counts of transfemicides in the country. This, Aguirre said, is due to the fact that, to date, transfemicide is only classified as a crime in five of the country's 32 states.

LGBTQI+ rights organizations that attempt to keep records say that between 50 and 70 trans people are murdered in Mexico each year. However, foundations such as Letras S warn that cases are underreported, given that some murders are not officially reported or are not recorded as murders of trans people due to gender identity.

This lack of visibility in institutional statistics is one of the reasons why journalists don't give the problem the coverage it deserves, Aguirre said. He compares it to how murders of women — a crime that also occurs with great frequency in Mexico — were treated until recently.

“It was only in recent decades, when femicide began to gain visibility through statistics, which are always very scandalous, that media turned their attention to the issue, and thousands of reports, studies and investigations have been written,” Aguirre said. “That's not happening with transfemicide. Why? Because there are no statistics, for starters.”

However, statistics aren't essential for addressing the phenomenon through journalism, Aguirre said. There's plenty of evidence that there's a structural problem of violence against the trans population that needs to be adequately covered, he added.

"It doesn't matter if it's 400, or 10, or one a year. It's a phenomenon; it exists. It's a social problem. So, since it's a social problem, it's the journalist's obligation to address it," he said.

On Feb. 13, 2024, the body of Elisa Cortez, a 24-year-old trans woman, was found in a ranch in the state of Tabasco. Some local media outlets that covered the crime did so by revealing her birth name and misgendering her, according to Agencia Presentes, a regional news outlet specializing in gender and sexual diversity issues.

About a month later, Landeros and Aguirre interviewed the young woman's mother as part of their research for "Transfeminicide." That interview, they said, taught them the importance of empathy when covering such issues.

“To be a journalist interviewing the mother of a woman who has just been murdered requires the greatest empathy in the world, the greatest patience. But above all, to achieve that, we need to be humane journalists,” Aguirre said.

Having empathy while reporting includes everything from knowing how to listen to victims or their families, to allowing enough time for interviews, wearing the appropriate clothing and adopting the right attitude to inspire trust and closeness with your sources, Landeros said.

Only with this empathy, Aguirre said, can media hope to make journalism a factor in raising awareness and understanding of the problem in society, and thus stop contributing to stigma and violence.

No, @DiariodeMorelos. No asesinaron a un hombre vestido de mujer. Mataron a una mujer trans.

Los medios y periodistas tienen una gran responsabilidad de informar sin estigmatizar a comunidades vulneradas. La transfobia se normaliza con esta deficiente ética periodística. pic.twitter.com/UDQLGhTgZP

— Alex Orué (@Alex_Orue) April 6, 2021

"If we explain to the reader why a transgender woman is transgender, why their very circumstances push them into sex work, why they have to live in precarious conditions, why their world is often drugs... If we put all of that into a story, we hope that when the reader reads it, they will be empathetic, and with that empathy, we can begin to change the current circumstances," he said.

Additionally, Zacarias said journalists covering violence against transgender populations must understand the responsibility that comes with how they report on the issue. This includes training on sexuality, gender, human rights and gender perspectives, he added.

“I think this type of training is needed because it can help people become more aware and sensitive to all these issues,” he said. “And they need to understand that inclusive language doesn't mean using an 'x' or an 'e' [at the end of words]. It really means including diverse identities and including all people without falling into prejudice, stereotypes and stigma.”