Most Latin American countries have laws on transparency and access to public information. Even some of these laws, such as the Mexican and Brazilian laws, are considered among the best in the world, according to a UNESCO report published in 2017.

These laws seek to guarantee that journalists and citizens in general have access to documents with relevant information on the actions of public agencies and officials, and establish that the State is obliged to deliver this information in open digital formats.

However, in practice, access to public information in Latin America is not so simple. Frequently, journalists requesting public data find that agencies deliver the information in unstructured formats, such as PDFs, text files or scans, in which the data is disorganized, making its analysis a very complex task.

Mago Torres, from Northwestern University's Knight Lab, moderated the DockIns presentation via streaming, with the participation of Delfina Arambillet, from La Nación; and Michael Morisy from MuckRock. (Photo: Screenshot of a YouTube live streaming).

"In Latin America, most public data is in large volumes of unstructured documents. It's not like you can press a button and download a CSV format file and have everything structured, beautiful, and be able to analyze to see if there is corruption or know what the State is buying," Delfina Arambillet, data and innovation journalist at La Nación newspaper in Argentina, told LatAm Journalism Review (LJR).

Several news and technology organizations around the world have developed digital tools to facilitate the analysis of unstructured documents, most of them based on artificial intelligence. However, for most small and independent media in Latin America, it remains difficult to access and use these technologies in their investigations.

With this problem in mind, Arambillet and a team of journalists from different newsrooms in the Americas joined forces to create a tool that seeks to democratize the use of artificial intelligence for the analysis of large amounts of documents for media that do not have technical experts in their teams.

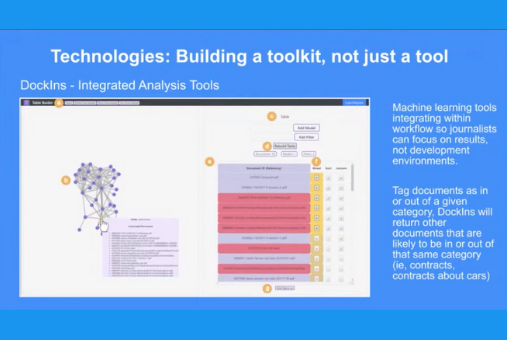

We’re talking about DockIns, a tool that, through machine learning and natural language processing (NLP) techniques, analyzes and classifies documents with unstructured content, extracts information from these documents and identifies topics and entities, that is, the most important chunks of information in a particular text.

The tool was developed in 2021 as part of Collab Challenges, a global initiative of JournalismAI and Google News Initiative that brings together media from multiple countries to develop innovations in journalism using artificial intelligence. Arambillet and his La Nación colleagues Momi Peralta and Martín Pascua teamed up with Claudia Chávez, Gianco Huamán and Gianfranco Rossi of Ojo Público (Peru); Rigo Carvajal of CLIP (Costa Rica); and Mitchell Kotler and Michael Morisy of MuckRock (United States).

"We agreed that we had in common that accessing purchasing data in our countries is difficult and that most [of this data] was in these unstructured documents, in different places, in the middle of chaos," Arambillet said. "We wanted to find a way to develop a tool, a method that could help the journalist find insights quickly and a little bit easier, and without requiring so much of the work of programmers."

Ojo Público is one of the few Latin American newsrooms with experience in the use of artificial intelligence for the analysis of large amounts of documents. In 2019, the Peruvian digital native media, specialized in investigative journalism, developed Funes, an algorithm that facilitates document analysis and finds risk indicators to detect possible traces of corruption in public procurement.

MuckRock has DocumentCloud, its open source platform for document hosting and analysis, and has developed SideKick, a machine learning tool integrated with DocumentCloud, designed to classify documents according to user-defined tags.

The team behind DockIns took some of the work that MuckRock had developed and added programming layers to make it capable of working with Spanish-language documents, as well as optimizing its tagging and classification capabilities.

"DockIns] allows a journalist to upload large volumes of documents and, from those documents, find entities, for example streets, names of people, names of companies, amounts in countries, etc., and find connections between those documents and, in turn, make a classification of those documents," Arambillet explained.

To recognize these entities, the tool uses NER (Named Entity Recognition), a natural language processing technology that identifies key elements in a text, which helps classify unstructured information and detect relevant information.

"Once you go through this entity recognition procedure, what you do is classify the documents by topic. What the tool does is, based on an algorithm, find out what topic they may be talking about. For example, if it is a purchase, a call for bids, a food purchase, an arms purchase…," the journalist said. "You can customize the tool to 'train' the algorithm to recognize different topics."

In a next step, the tool allows for finding relationships between documents from the extracted entities.

The advantage of DockIns is that it does not require writing code or programming to train the algorithm, but rather, based on the results it produces, the user can qualify its performance and this refines the quality of the results according to specific needs.

"The system's intelligence is constantly feeding back on what you are doing, in the sense that if today you classified 10 documents and classified them by topic, that is assigned to that project. Then, later, you assign another ten documents and a history of that education is generated," Martín Pascua, a developer at La Nación, who was part of the team that created DockIns, told LJR. "When you pick up this project again, you already have the previous classification and you train it again, so it is a constant retraining."

During the six months of the Collab Challenge, the DockIns team spent a lot of time testing different models of NER, researching different tools and performing trial-and-error procedures to optimize the platform as best as possible. At the end of the project, the team managed to complete a prototype of the tool and a workflow for any journalist to perform the procedure.

"The base creation of the workflow was that, with all the tools out there, in what way can we put them together and make the actual task easier for the journalist," Pascua said. "One part was adding certain layers of development to DocumentCloud and another little bit was documenting the workflow so they can use it."

Most of the team members are still in communication with the intention of building a tool that combines all the elements developed in an end-user interface.

"The idea is to create an interface that brings together all the workflow in one interface. Imagine an input where the journalist can upload documents, process them and visualize the results," added Arambillet.

Once the tool has been implemented, it will not only speed up investigations based on public data and save journalists hours of work reading and classifying documents, deciphering their content and finding relevant entities, but it will also help to analyze any type of unstructured documents for almost any type of data-driven investigation.

"The tool was conceived to be able to investigate public documents that are made in such a way as to not be investigated, or also because of the State's habit of not digitizing them. But it can also have other uses: if you have a lot of PDFs and you want to see what they are about, what things they contain, etc., this can be used to find insights quickly," Arambillet said.

Although DockIns is still in the prototype phase, its creators believe that this open use in Latin American newsrooms will contribute to democratize the use of artificial intelligence to process information contained in large amounts of unstructured documents.

"I believe that innovation lies in facilitation, in being able to provide tools and allow people who don't know how to code to execute and run these analyses," Arambillet said. "It's very difficult to read documents and find insights, it's almost a nightmare, so I think that's the innovation: to make it easy in every sense for the journalist to be able to access these analyses and also to be able to provide the information that otherwise could not be analyzed."

The team found that the different machine learning and natural language processing applications they tested during DockIns development performed optimally with English documents, but not with Spanish files.

The tool allows you to upload large volumes of documents and find entities and connections in them. (Photo: Screenshot of a YouTube live streaming).

The Spanish-speaking members of the team worked on tweaking the tool to perform similarly with documents in both languages so that it would be efficient in newsrooms throughout much of Latin America.

"Everything that was put together was mostly in English. What we did was also a work that functions for Spanish language values," Pascua said. "The algorithms are prepared in English. So also this training and these layers had to be put together for them to work in our language."

With their collaborative work during the Collab Challenge, the members of the DockIns team proved the importance of developing partnerships between journalists and developers in newsrooms. At La Nación, close collaboration between editorial and technical professionals has been commonplace for several years, especially in La Nación Data, the data journalism area of the Argentinean newspaper.

For this reason, the organizers of the Collab Challenges will select this year two participants from each news outlet, one from the editorial team and one from a technical team, for their new collaborative initiative, called AI Fellowship Programme. The idea is to form five teams that integrate reporters, editors and researchers with developers, web designers and programmers from news organizations.

"The personal experience of linking up with a journalist also adds a lot," Pascua said. "Personally, I get a lot out of it because it transforms the technical part into something human, into something tangible, into understanding the real world problem of why this tool, why use it or how it can be improved. And that happens through synergy. [...] And the Collab Challenge boosted all that because we were also able to link up with other newsrooms, and see the way of thinking in other countries."

However, Arambillet acknowledges that the development of artificial intelligence tools is still something that requires significant economic investments that most media in the region cannot afford. Hence the importance of collaborative work and tools like DockIns, which seek to make these technologies more accessible.

"Technology itself can always do a lot of things that we can't do. And it is a great opportunity to give ourselves the space to learn how in the long term it will be much more profitable or much more beneficial for the news organization to be able to apply these technologies," Arambillet said.