It is no coincidence that pop culture’s most famous hero is a professional journalist. Superman, as well as his companions, Jimmy Olsen and Lois Lane, were presented as self-sacrificing journalists, capable of risking their lives to get the news and defend just causes.

Several generations have grown up with these romantic ideas about journalism, but little is said about the fact that, in real life, Clark Kent would be among the lowest-paid DC superheroes.

"I’ve always said that the only superhero journalist is Superman. Otherwise, we journalists have to eat, pay utilities, rent, support our family, etc.," Jefferson Diaz, a Venezuelan journalist based in Ecuador, told LatAm Journalism Review (LJR). "All this mystical feeling around the profession, that 'it's the best profession in the world,' as Gabriel García Márquez said, that unfortunately doesn't pay for food. It’s something we have to rid ourselves of as journalists. We must demand that our profession be protected and well remunerated because good journalism costs money."

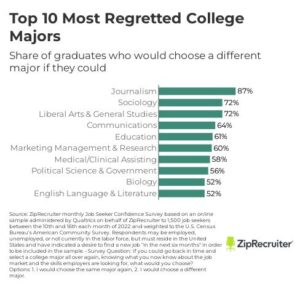

A study published in December 2022 showed that journalism was the college major with the highest percentage of regrets. Most of them explained their dissatisfaction with the difficulty in getting a job, poor salaries and lack of opportunities. In addition, fewer and fewer Latin Americans see journalism as a dream job and are veering towards other forms of communication such as being an influencer or a youtuber.

Map of South America of ideal employment. Photo: Remitly

"I think many people have stopped romanticizing the idea of journalism as the best job in the world, and are seeing it as just another job where you need to have clear rules and limits. Limits with ourselves, with our colleagues, with our bosses. And also to be very clear that we have the right to have a salary, to rest, and to have mental health," Jordy Meléndez, founder of Distintas Latitudes and Factual, an NGO dedicated to strengthening networks and the skills of Latin American journalists, told LJR.

In December 2022, Twitter was filled with complaints of job insecurity and abuse in Mexican journalism. One of the main complaints was the lack of decent contracts and social benefits.

"My first job [as a journalist] was an unpaid, full-time internship for half a year in the country's capital. Once I graduated, I was invited to return to the news outlet where I interned. I spent almost a year without a contract (despite the fact that the invitation was to a position with a contract and proper benefits). After that year, working up to 12-hour days, with no contract, no benefits, no insurance, no vacations and a couple of threats because of my work on political and gender issues, I decided to resign," Mexican journalist and writer Mariana Limón Rugerio told LJR.

"It was a learning experience and, at yet, very disappointing. I rethought my professional career and looked for a scholarship abroad," Limón Rugerio said.

This story repeats itself in other media and with other protagonists. Lidia Sánchez, a Mexican journalist and researcher, also denounced on social media the poor working conditions in Mexico after being fired from an important independent digital publication in the country.

"What happened to me is not an isolated case. I started my career when the modality of outsourcing was implemented. And with the exception of the times I’ve worked for news agencies, all the media in which I’ve worked I was hired under this format," Sanchez told LJR.

10 most regretted college degrees- Photo: Zip Recruiter

"The federal labor law in Mexico establishes that a company must cover the worker-employer contribution [for social security, retirement and housing support]. But the outsourcing modality allowed companies to hire you through third parties. So you worked exhausting hours for a single news company but according to the 'contract' you were only a contributor," Sánchez said.

Since 2021, outsourcing has been illegal in Mexico, but, according to those interviewed for this story, employment instability remains. Sánchez is currently unemployed and the job posts available to her offer low salaries.

"I've seen offers of 15,000 pesos a month [about US $800]. With inflation, in the middle of 2023, that salary is not enough for anything. Rents in downtown areas can go from 6 to 10 thousand pesos [around US$ 320 to 530] for a room in an apartment. And if you have a family? That's the same salary they offered 10 years ago when I graduated from the university," Sánchez said.

This situation repeats itself in other Latin American countries. "An increased precariousness for journalists in Latin America is our daily bread. I saw it when I worked for a Mexican news outlet. I saw it when I worked in Venezuela. I see it in Ecuador. I hear it from colleagues in Peru and Colombia," Jefferson Diaz said. According to Diaz, in Ecuador there is a law that requires journalists to be paid a minimum of US $980 per month. However, in practice, there is no compliance. Payment is agreed to as an honorarium [payment made to someone who independently performs a task for the company or person, either sporadically or temporarily].

This job insecurity multiplies when a journalist lives in cities or towns far from the country's capital. The salary gap between local journalists and journalists in large cities is enormous.

The Colombian organization Fundación para la Libertad de Prensa (FLIP) has denounced the precariousness of journalism in that country. In a study, they state that local news outlets in Colombia have very few financing options. Therefore, local journalists are in a survival situation because opportunities and circulation are very limited, the market is very small and salaries are extremely low.

"Local journalism that faces the most adverse conditions: Threats, intimidation, censorship, and self-censorship generated by political, economic and criminal group forces. To the immense burden on mental health this implies, we must add very low salaries, often with no contract, no medical insurance, no overtime due to conditions of extreme insecurity or 10 to 12 hour work days," Limón Rugerio said.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, it became more evident than ever how unprotected journalists are and how they work with no guarantees. In search of news, many went to hospitals without adequate protection, risking contagion. In Peru, during the first year of the pandemic, 161 journalists died from COVID-19, according to data collected by the National Association of Journalists of Peru (ANP, by its Spanish acronym). Of these, at least 77 journalists were infected while practicing their profession.

"It’s the sum of it all. You don't pay me, you pay me poorly, you don't offer me the tools to work with, you don't guarantee my safety and despite all that you ask me to 'wear the company’s colors,' because we journalists have to be selfless. What are we journalists doing to protect our profession?" Diaz said.

Due to salary conditions, more and more journalists are deciding to seek alternative sources of income or follow other professional paths.

In Venezuela, for example, studies have shown that journalists in general receive insufficient remuneration in their jobs. "I stopped practicing journalism formally in March 2022, because conditions in Venezuela are abysmal. My salary, at that time, was US $180 plus a "bonus" in Bolivars that devalued day by day. They also asked me for exclusivity," a Venezuelan journalist who preferred to remain anonymous told LJR.

Jordy Meléndez has followed the career of several generations of journalists in the region through the Latin American Network of Young Journalists. He’s been able to observe how young people with a lot of enthusiasm for journalism end up working in advertising agencies, marketing, political communication, tech companies, among others, for economic reasons. "I think there is now a less romantic vision of journalism," Meléndez said.

The situation is so widespread that in the 13th issue of the current series "Superman The New 52,″ Clark Kent gets tired of putting up with the demands of his bosses and seeing how the Daily Planet changes its editorial line, that he decides to quit his job and forge an independent path.

Sometimes, fiction ends up reflecting current trends.