Brazilians are the most untrusting of the press' ability to recognize its own mistakes when compared to Indians, the British and Americans, according to survey data from "Overcoming indifference: what attitudes towards news tell us about building trust.”

The report, published Sept. 9, is part of a larger project from the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism (RISJ) on people's trust in the news, and has collected data in four countries: Brazil, India , UK and the U.S.

For the survey, RISJ worked with three research companies: Datafolha in Brazil, Internet Research Bureau in India, and Kantar in the U.S. and UK. About 2,000 people were interviewed in each country, in a sample representative of the local population, between May and June 2021.

One of the points that caught the attention of researchers concerning Brazil was the portion of the population that believes news organizations try to hide their own mistakes: 78 percent. The rate is 64 percent in the UK, 59 percent in the U.S. and 55 percent in India. Among Brazilians, only 20 percent believe that journalism companies are willing to recognize their mistakes (2 percent did not have an opinion).

Camila Mont'Alverne, co-author of the study and postdoctoral fellow at RISJ (Courtesy)

“We found that Brazilians are in some cases even more skeptical of journalists than interviewees in the other countries. [...] Even those who are generally trusting toward news are suspicious that journalists tend to cover up their mistakes,” Camila Mont’Alverne, co-author of the study and postdoctoral fellow at RISJ, within the Trust in News project, told LatAm Journalism Review (LJR).

Brazilians also seem to have negative opinions about the press more often than citizens of other countries. For example, 44 percent of Brazilians think that journalists commonly and intentionally provoke to draw attention to themselves, and 43 percent believe that media professionals often try to manipulate the public – rates are the highest found across countries surveyed. At the same time, 36 percent of Brazilians believe that journalists are commonly paid by their sources, second only to India, with 37 percent.

But, Brazilians are not always the most skeptical of the press. For example, the majority of respondents in all countries believe that journalists double-check facts with various sources very often or sometimes, and the percentage of Brazilians is among the highest: 72 percent in India, 70 percent in Brazil, 66 percent in the UK and 63 percent in the U.S.

Profile of the untrusting and democracy

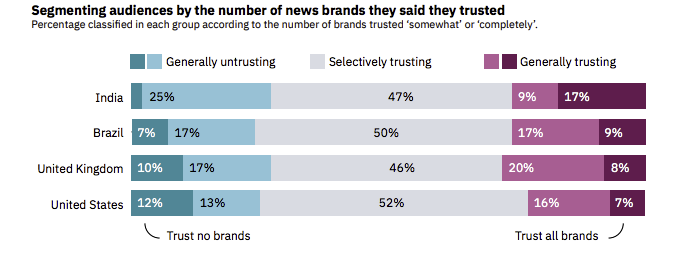

In the survey, respondents were separated into those who are "generally untrusting," "selectively trusting" and "generally trusting" of the news – the ranking was made considering the average of journalism brands that respondents said they trust in each country. In Brazil, 24 percent of people were in the category of those who are "generally untrusting."

Graph showing the segmentation of respondents by level of confidence in the news. (Screenshot)

The researchers argue, in the study, that this segmentation allows a better comparison between countries and helps to understand the problem in a more complex way, because “a well-informed, thoughtful news consumer is discerning about the sources they encounter; they know which sources of news they can trust but they also know which to be skeptical of and why,” the study said. “In other words, blanket trust of all news may be just as unhealthy as generalized distrust of all sources."

Based on this segmentation of the respondents, several aspects of the profile of those who are "generally untrusting" of the news in Brazil differ with the same group in other countries. One of the main ones, highlights Mont'Alverne, is the association with democracy. In the countries surveyed, people who rely less on the news tend to be more critical of how democracy works in their societies. This result suggests that trust in the news may be influenced by factors external to the press itself.

In the U.S., perhaps a reflection of political polarization, 73 percent of Americans who are "generally untrusting" of the news are dissatisfied with democracy – a rate that is only 22 percent among those who are "generally trusting."

In Brazil, there is almost no difference in this regard. "Both groups are highly dissatisfied. This is not something new, since Brazilians have been unsatisfied with how democracy works in their country for a long time, but the role of the press in this dynamic appears somewhat distinct compared with other countries," Mont’Alverne said.

Men, older, white and from the South

The profile of a Brazilian who does not trust the news coincides, in some aspects, with that of other nations. For example, they tend to be older in all countries surveyed. In Brazil, 38 percent of those who are "generally untrusting" are over 55 years of age and, among those who are "generally trusting," 42 percent are under 35 years of age.

Likewise, the untrusting are mostly men, which is repeated in Brazil and India (59% of the group) and, to a lesser extent, in the United Kingdom (53%) – in the US, they are evenly distributed between genders. In Brazil, there is also a racial and regional factor: the untrusting are mostly white and concentrated in the southern region.

Interestingly, in all countries, the untrusting tend not to have higher education, except in Brazil, where education seems to have no influence on this. In India and the United Kingdom, those who are "generally untrusting" tend to come from low-income families, while in Brazil it is the opposite, they are less likely to be among the poorest.

“We found no relationship between education and trust in news in Brazil and this is another difference from the other countries. However, other studies have also shown that education is not necessarily a predictor of trust in news, nor does it always follow a consistent pattern (in some cases, those who are more highly educated trust news less),” Mont’Alverne said.

She said that Brazilians with higher education tend to demonstrate familiarity with journalistic concepts, such as the difference between a reporter and a commentator. That is, for this portion of the population, perhaps media education does not necessarily reinforce confidence in the news.

Benjamin Toff, senior researcher at RISJ and leader of the Trust in News Project (Courtesy)

“From our qualitative interviews in our previous report, many Brazilian interviewees who were highly educated also demonstrated that they had some notion of how news works, but they objected to what they saw as an undue political or commercial influence,” Mont’Alverne explained.

Study co-author Benjamin Toff, senior researcher at RISJ and leader of the Trust in News Project, agrees.

”In other words, education and media literacy may help to demystify aspects of journalism for some, but it can also lead people to embrace additional reasons for being skeptical towards news,” he told LJR.

Supporters of Bolsonaro

The study also analyzed the political profile of the untrusting and, in Brazil, they are in their majority, 53 percent, supporters of President Jair Bolsonaro, known for his recurrent and virulent attacks against the press.

Asked if the untrusting Brazilian, identified as an elite (white, male, from the South, older, less likely to be among the poorest strata) always had this profile, or if this is just a portrait of the current political moment, the authors responded that the survey data do not allow us to know this, but that they intend to explore this theme in future studies. However, they believe that these characteristics are likely to be changeable.

"It is very possible that the profile of the untrusting towards news is particularly connected to the current political context, considering that the profile of the generally untrusting is very similar to those who support the President now. That dynamic is most similar to what we see in the United States where the profile of the untrusting looks a lot like supporters of Donald Trump, as well as people who are less interested in politics altogether,” Toff said. “As political coalitions change, attitudes towards the press could also change. There are some indications of that in our data.”

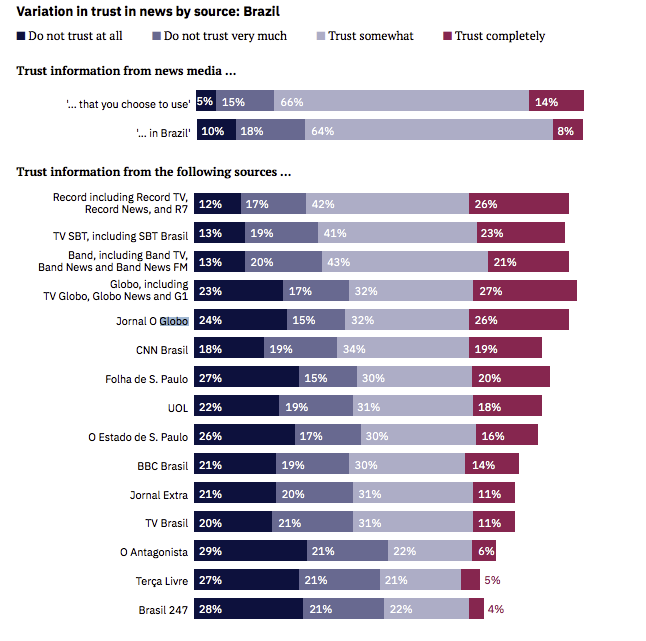

The indications he refers to appear in people's trust in specific journalism brands. In Brazil, the study identified a partisan bias in relation to Globo (TV Globo, Globo News and G1): 83 percent of supporters of the Workers Party (PT) said they partially or totally trusted information reported by the brand, a proportion that is 54 percent among those who are not PT supporters.

Chart showing Brazilians' confidence in journalism brands. (Screenshot)

According to the report, this is a change in relation to the period when the party held the presidency, when PT members were very critical of the press, especially Globo.

“The fact that supporters of the Workers’ Party (PT) are more trusting towards Globo, for example, that may not have always been the case and could probably change again if Lula wins the elections next year. It is something we will be paying closer attention to over the coming years with our additional rounds of data collection,” Mont’Alverne said.

On the issue of gender, the researchers say it is curious that men are more untrusting in Brazil, because data from the study show that they access more and are more interested in news than women, a behavior that is generally associated with greater trust in the press. Toff says the authors intend to investigate this further in future studies, especially if gender has different impacts between supporters and opponents of Bolsonaro.

“Previous research in the U.S. has shown something similar where gender operates in different ways within political parties than it does between parties. It’s possible or even likely that the overall pattern we find of men being more untrusting towards news masks some important differences among different segments of the public,” Toff said.

How to regain trust

One of the main conclusions of the study is that people who least trust the news are the most indifferent, not necessarily the most hostile towards the press. That is, they are people who care little about editorial practices and don't have many opinions about how reporters, editors and organizations should do their jobs.

“This suggests that, to some extent, the problem news organizations have with less trusting audiences is proving that news offers something relevant for their lives,” Mont’Alverne said.

Toff suggested that the press needs to make the connections between its work and people's lives clearer. According to him, in qualitative interviews, many interviewees complain that journalism tends to focus on topics they don't care about.

“A lot of the time, journalists who cover political and civic affairs think the importance of their coverage is self-evident and may not take the time to make the case for why what they cover should matter to audiences,” Toff said. “Covering politics for people who are uninterested in politics is a challenge, and nobody wants to be talked down to, but these generally untrusting audiences aren’t looking for the same kind of coverage as people who are interested in politics but think the press makes their favored politicians look bad.”

In addition, he points out that this audience demonstrates an inability to differentiate between journalism brands, and many tend to be skeptical of all media. For this reason, he recommends that news companies have more visible identities and brands, making it very clear, even to the public that does not follow that media outlet, why the information they produce is different from others. Toff explained that negative views about journalism are widespread, such as the idea that professionals accept money from sources or do not verify information.

“Many people think there is minimal difference between professionally produced news and everything else they may see in their social media feeds,” he said. “Journalists and news organizations are often reluctant to insert themselves into the news and often prefer to take a more detached stance. But, there are many critics of news who will gladly step in and advance their own narratives about how professional journalists operate if news organizations don’t take more of an initiative to make that positive case for themselves.”