*By Brenda Focás and Marina Moguillansky, originally published on the website of Anfibia Magazine.

Fed up. News saturation. Need for disconnection. These feelings do not only appear with the dullness of the new year. The reaction appeared as a trend but intensified in the post-pandemic period.

During the first months of the pandemic, almost the entire news agenda was dominated by COVID-19, with very high levels of consultation on news sites, television and radio. As a result of quarantine, the great uncertainty about the evolution of the virus and the measures the government was taking, the main social activity was to consume news. The media turned into a long newscast, and permanent press conferences and curves showing the exponential growth of contagions made up the information menu. 2020 was the year of over-information and audience saturation.

In the early days of the pandemic, spending day and night consuming information through different media and platforms was a common habit. Lucila, 34, was working in real estate and living in Palermo, in the city of Buenos Aires, Argentina. She recalls: "I watched all the news, read newspapers on the internet and social media, followed all the news." This hyper-exposure was combined with the fact that the media agenda was dominated by news about the pandemic.

As Elsa, a 78-year-old retiree, recalled, "any newscast you put on, they talked about COVID-19. There were no other programs, there was nothing else to watch." According to data from the Media Observatory of the National University of Cuyo, in Mendoza, Argentina, in March 2020 almost 90% of digital media news focused on the coronavirus. In addition to over-information and saturation, there was a disinformation effect as there were conflicting versions on such sensitive issues as health, even from legitimate sources such as the WHO.

One of the central issues during the pandemic was media consumption and the approach to news during quarantine. Different studies show that during the first months of the quarantine there was a great demand for information which resulted in saturation. Paradoxically, when Argentina had the highest rates of COVID-19 infection, media interest dropped to give way to other issues on the agenda.

In a recent survey carried out by the Núcleo de Estudios sobre Comunicación y Cultura (Center for Communication and Culture Studies or NECyC, by its Spanish acronym), we inquired about the perception of the media coverage of the pandemic. Among the participants, 63% disagreed with the statement "the media transmitted correct and useful information and they evaluated the coverage negatively. Adopting the same critical stance, 46.9% agreed with the statement that the media are highly politicized. Audience perception seems to indicate that after some months of consensus and support for the quarantine, the media took a position - in this case, in favor or against the national government - biasing the news coverage.

This saturation scenario led to a new habit: After the pandemic happened, a large part of the audience stopped consuming news. Currently, only one out of four people say they get information every day on digital news sites, while one out of two people never read newspapers or listen to the radio. Regarding television, only 22.2% said they watch newscasts every day, 29.2% said they do it sometimes and 39.4%, never. In line with other research, media fatigue appears as a trend in communication practices of the times.

Natalia, a Psychology student at the University of Buenos Aires (UBA), said: "During the first months of 2020, I consumed all kinds of news. Then I stopped watching them because it was making me ill. There was so much death and hate on TV that I said, well, I think I'd better read books, watch series." Like her, many stopped turning on the TV and listening to the news to preserve their peace of mind during the pandemic.

What prevails these days is the incidental consumption of information. The habit had already settled as a practice (Mitchelstein and Boczkowski, 2018) and became more acute during the first months of COVID-19. That information comes across to us, comes out to find us. Through social media we receive news from websites, television and radio clips.

Juan, 18, lived with his parents in Palermo, Buenos Aires, and said that during the pandemic "I didn't make a conscious effort to say: 'I'm going to read the newspaper.' But I ended up getting information because someone posted something on Twitter, which is the only way to get information now." Although this practice prevails among younger people, it has become more frequent in other age groups as well. In the survey mentioned above, one out of every two people said they get information through social media.

The percentage of people avoiding the news has increased in all countries. This has also been confirmed by the latest Reuters global report. This type of selective avoidance has doubled in both Brazil (54%) and the UK (46%) in the last five years, with many people commenting that news has a negative effect on their mood.

Claudia, 47, is separated and lives with her two children in La Plata, Argentina. She has a natural foods store, so she worked during the pandemic. "At first we watched a lot of newscasts, all the time. Until one day, switching between TN, C5N and América, I said 'This is a circus.' I felt I had to remove myself from all that. My children and I agreed not to watch them anymore."

Something similar happened to Helena, 42, who works in marketing and communications. She is the mother of three children and lives with them in Almagro, in Buenos Aires. "At first, I followed the minute-by-minute news of the pandemic. Then I took some distance because I started to feel exhausted and numbed by the subject. I started to watch less, every once in a great while."

A significant percentage of younger and less educated people said they avoid news because it can be complicated to follow or understand. This suggests that the media could do much more to simplify language and better explain or contextualize complex information. The disconnect also signals difficulties in engaging certain audiences in the digital environment.

At the same time, we found that the percentage of people who say they are very interested in news has declined over time in all markets: This is a trend that accelerated despite the pandemic. In 2022, interest in news was lower in the vast majority of countries. In some, such as Argentina, Brazil, Spain, and the UK, these declines have been accumulating for some time.

Do we believe the news, or do we distrust media information, and are there differences when it comes to social networks? In our survey we observed that 52.3% answered that they get their information through social media. The interesting fact is that, in social media as a whole, 37.5% chose direct information from accounts or walls of politicians, journalists or institutions. Another 37.4%, said they get their news from digital portals that other users post. And 25.1% mentioned content received through WhatsApp or other messaging apps. These data show the role that these and other direct sources play in the dissemination of information content.

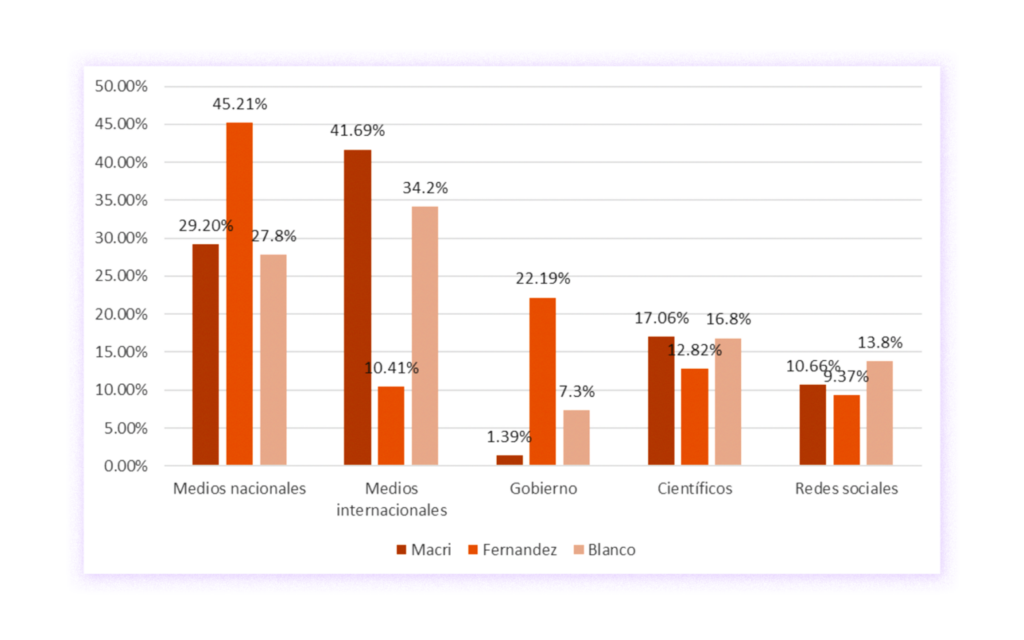

The question of trust and credibility of sources became central in a scenario of political polarization and fragmentation of the information agenda. In the survey, we asked which sources of information were most trusted during the pandemic: 38% pointed to national media, 24% to international media, 15% to scientists, 13% to the government and 10% to social media. The trust relationship was mediated by the political identity of the respondent. Thus, people who voted for the ruling party said they trust the views of scientists (in particular, they mention infectious diseases specialists or doctors who usually appear in the media) and also some government figures. Opponents usually mention a particular channel or journalist they trust. The survey also shows contrasts in the level of trust according to the vote.

Of the following actors, which do you find most reliable as a source of information about the pandemic?

Source: Research NECyC-PASCAL (2022)

For those in favor of the government, the most chosen source was the national media, followed by the government, then scientists, international media and finally social media. For opponents, the most reliable source was the international media, then the national media, scientists, social media and, finally, the government. The greatest contrast between opponents and supporters of the government was observed in the trust or distrust in international media as a source: 41.69% of opponents chose it, compared to 10.41% of government supporters. This contrast is also reflected in the level of trust in the government as a source: 22.2% of those in favor of the government chose it, against 1.4% of those opposed. These data reinforce the antagonistic panorama of the media system and the polarization in relation to the consumption of information during the pandemic.

Clara, 72, is retired, and previously worked as a systems analyst. She voted for Juntos por el Cambio [a political alliance led by former Argentine President Mauricio Macri]. "If I look for information, unfortunately it has to be from foreign media, from correspondents who are abroad, because I don't trust the media here. I am very alert to fake news, I use Twitter a lot, but if my common sense tells me that something can't be what they’re saying it is, I google it and try to find a reliable source."

Eva, 36, is a tango teacher, has three children and votes for the Frente de Todos [a coalition led by Argentine President Alberto Fernández]. During the pandemic, she had no income because milongas and dance classes were cancelled. However, she said: "I have a lot of confidence in the Ministry of Health, and in the national government. I feel a lot of gratitude because if this had happened with the previous government, it would’ve been terrible. I listen to the radio a lot and I read digital newspapers, day-to-day reporting, the presidential announcements."

Raúl, 66, a food business entrepreneur, said he can’t stand the media’s politicized discourse. He does not identify with Kirchnerism [the government] or with Macrismo [the opposition], but in the 2019 run-off election he did vote for Macri, reluctantly. "No media is apolitical. I cannot watch C5N and I cannot watch Channel 13 because they are two sides of the same coin. Sometimes I try, I make the effort, but I really can't." The above are three different ways of thinking about the world.

This sampling shows the dynamic evolution of how we relate to information during and after the pandemic. The initial search for news, the overexposure and an agenda dominated by COVID-19 as the only topic later led to saturation, disconnection and distrust. The way we evaluate information sources, in a scenario of growing polarization, appears to be closely related to the political position of individuals, thus fragmenting the scenario. The survey and interviews confirm an occasional consumption of news and the need for disconnection as increasingly frequent practices among audiences. These phenomena take place hand in hand with a drop in trust in media information, a decline in interest in news and an increase in those who avoid it on purpose.

Banner image: Jael Díaz Vila/Revista Anfibia