It’s been two years since Guatemalan journalist José Rubén Zamora was taken to prison. On July 29, 2022, authorities simultaneously raided his home and the headquarters of newspaper elPeriódico without offering many explanations. After hours of searching, the journalist was taken from his home with shackles on his wrists, in an operation that looked like it was meant to take down a drug trafficker.

Since then, he has been in the Mariscal Zavala prison, accused of money laundering, blackmail and influence peddling. Despite the fact that his prison conditions have been considered torture by the UN, despite having a trial annulled and described by organization Trial Watch as “unfair,” and despite the irregularities reported in his legal case – which include the persecution of his defense lawyers – the journalist remains in prison. Hearings for a new trial into the money laundering charge and to define the situation for the two other charges against him have not yet been scheduled.

For national and international press freedom organizations and legal experts, the case against Zamora has signs of being a reprisal for his journalistic work. For that same reason, several point out that in addition to Zamora himself, authorities had another victim in their sights: elPeriódico, the newspaper he founded.

Indeed, despite the struggle of journalists, editors and owners of the media outlet to keep the publication going after Zamora's arrest, economic suffocation and the safety of its own journalists led to its definitive closure on May 15, 2023.

Men sort and count newspapers to distribute them. The delivery men gather their copies for the last time, in the early hours of Nov. 30, 2022. (Photo: Simone Dalmasso / Courtesy of Plaza Pública)

“In the end, that was what they wanted with the imprisonment of José Rubén. In addition to punishing José Rubén […] it was to remove that annoying media outlet. Not having to answer uncomfortable questions, not having to see those covers that questioned them,” Marielos Monzón, one of the members and founder of the No Nos Callarán (They will not shut us up) collective, told LatAm Journalism Review (LJR).

This is also the opinion of José Carlos Zamora, son of José Rubén and director of communications at Exile Content. According to what he told LJR, in addition to punishing his father directly, this persecution had the objective of not only shutting down elPeriódico but also of telling other journalists that “doing journalism is a crime.”

“The good thing is that my father is extremely resilient, and despite the circumstances, he remains firm in his principles and convictions. He even sees his arbitrary detention as part of his job, since it helped expose the corruption and abuse of power of the corrupt authoritarian regime,” he said.

Mentioning José Rubén in Guatemala is synonymous with journalism. This industrial engineer deeply believes in the role that journalism plays in democracies. In 1990, together with other investors, he created Siglo 21, a media outlet that also “played a fundamental role in strengthening democracy,” his son José Carlos said.

After leaving the publication, José Rubén made it his mission to expose corruption, organized crime and human rights abuses in Guatemala.. Coinciding with the culmination of peace negotiations that put an end to a 36-year conflict in the country, he founded elPeriódico in 1996.

Every day for almost 27 years, he would read the newspaper in its entirety – from the first to the last page.

At its most successful, elPeriódico had a circulation of 500,000 and employed 400 people.

The newspaper never cost more than US$1, but it was considered the “investigative media outlet par excellence” in Guatemala, according to Monzón. It was in tabloid size, circulated daily and published major investigations on Mondays. So, it was common for Guatemalans to wait for that edition to learn about a new case of corruption, or as they say in Guatemala, to find out who was receiving “un periodicazo,” as Monzón said.

Luis Aceituno, culture editor of elPeriódico, looks through the last print edition of the newspaper, at the printing press headquarters, in the early hours of Nov. 30, 2022. (Photo: Simone Dalmasso / Courtesy of Plaza Pública)

Investigations by elPeriódico not only had an impact with readers, they also had an effect on the judicial branch, which opened cases based on the information it published. They also earned it some recognition, such as when the newspaper received the King of Spain Award in 2021 as an outstanding media outlet in Latin America. José Rubén has received, among others, the International Press Freedom Award from the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ), the Maria Moors Cabot Award from Columbia University, both in 1995, and recently the Recognition of Excellence from the Gabo Foundation.

“My independent journalism has forced me to denounce the abuses and excesses of the established powers, corruption and impunity, state terrorism and the criminal acts of the high military command,” José Rubén wrote in his acceptance speech for the Gabo award, which was read by his son José Carlos.

This has earned José Rubén the title of “the most threatened journalist in Guatemala,” said Julia Corado, director of elPeriódico in recent years, who spoke to LJR from exile. Attacks against the newspaper and Zamora have included smear campaigns, cyberattacks, commercial boycotts, judicial harassment, constant audits from tax officials, death threats, murder attempts and an abduction.

And although there were also clashes under former presidents Otto Pérez Molina (2012-2015) and Jimmy Morales (2016-2020) over the breakdown of democratic institutions, it was under the administration of Alejandro Giammattei (2020-2024) that elPeriódico received the lethal blow.

During the 137 weeks of Giammattei's government and while Zamora was still free, the newspaper published an investigation every week on alleged cases of corruption that reportedly involved him. The final straw may have been an investigative piece about Giammattei allegedly receiving money in return for allowing a Russian company to develop a mine in the country.

As a founder, but above all because he was “an inexhaustible source of information,” most of the investigative topics were proposed by Zamora, Corado said.

"Those issues were what ultimately led him to jail," she said.

Monzón recalls how, as soon as news of the raid was made public in 2022, a journalists' chat was spontaneously activated and everyone offered to help elPeriódico ensure that day’s edition would be published. Because elPeriódico's printing presses were not accessible, another media outlet – which sources preferred not to give details about – offered to print the newspaper at their facilities.

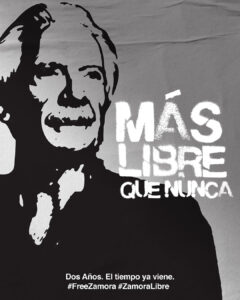

To mark his two years in prison, the Inter American Press Association (IAPA) shared with its members a series of works by José Rubén Zamora. (Courtesy of IAPA)

“It was seen as a victory,” Monzón said. “Every day [that it was printed] was seen as a victory against this pact of corruption, this pact of criminalization, until it was unfortunately closed.”

The absence of José Rubén had an emotional and economic impact. He was in charge of obtaining the resources. And although his arrest was always presented by the authorities as being related to his activity as a businessman and not to journalism, the raid on the newspaper’s headquarters and the freezing of its accounts reveal another reality. In fact, the accounts remain frozen to this day despite a judge ordering their lifting.

In addition, 10 journalists from elPeriódico were charged with “obstructing justice” after reporting on José Rubén’s legal case.

“It is striking that it was like revenge,” Monzón said. “There is this feeling that what they were doing was taking revenge, through José Rubén, on journalism.”

The outlet was able to operate for months with donations and grants from close friends and organizations such as the Media Development Investment Fund, the Knight Foundation, the International Center for Journalists (ICFJ), the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) and the Rockefeller Brothers Fund, José Carlos said.

However, its last print edition was published on Nov. 30, 2022.

“For the corrupt, it was a relief to stop seeing themselves in the printed pages,” Monzón said.

With a team of 30 people and based on its 12,000 digital subscriptions, elPeriódico focused online. However, on May 15, 2023, it closed permanently.

“It was extremely sad for him [José Rubén], his team, family and Guatemalans when it finally closed. But it was unviable and irresponsible to continue when there were no more funds, and the persecution of the team and advertisers continued,” José Carlos added.

For Wilmer González, a member of José Rubén's international defense team, the elPeriódico case is undoubtedly also part of the violation of the journalist's freedom of expression. The freezing of accounts, the persecution of advertisers and the statements of the prosecutor in charge of the case indicate that "elPeriódico was among the targets to be eliminated," he told LJR.

For this reason, they are requesting compensation from the State for the closure of the media outlet based on previous decisions of the Inter-American Court of Human Rights.

The information vacuum left by the closure of elPeriódico has been filled with more journalism despite the fear that this case has generated. Prensa Comunitaria and Plaza Pública, which is known for investigations, are some of the digital native media that have stepped in.

For their part, Corado and elPeriódico’s last editor in chief, Gerson Ortiz, launched EP Investiga initiative last April, with the same mission as elPeriódico.

“That is to say, they wanted to silence us, but they couldn't,” Ortiz told LJR. “Okay, they closed ElPeriódico, but Guatemalan journalism is still alive and we are going to continue doing journalism. I think that is always good news.”